It hit him like a thunderbolt.

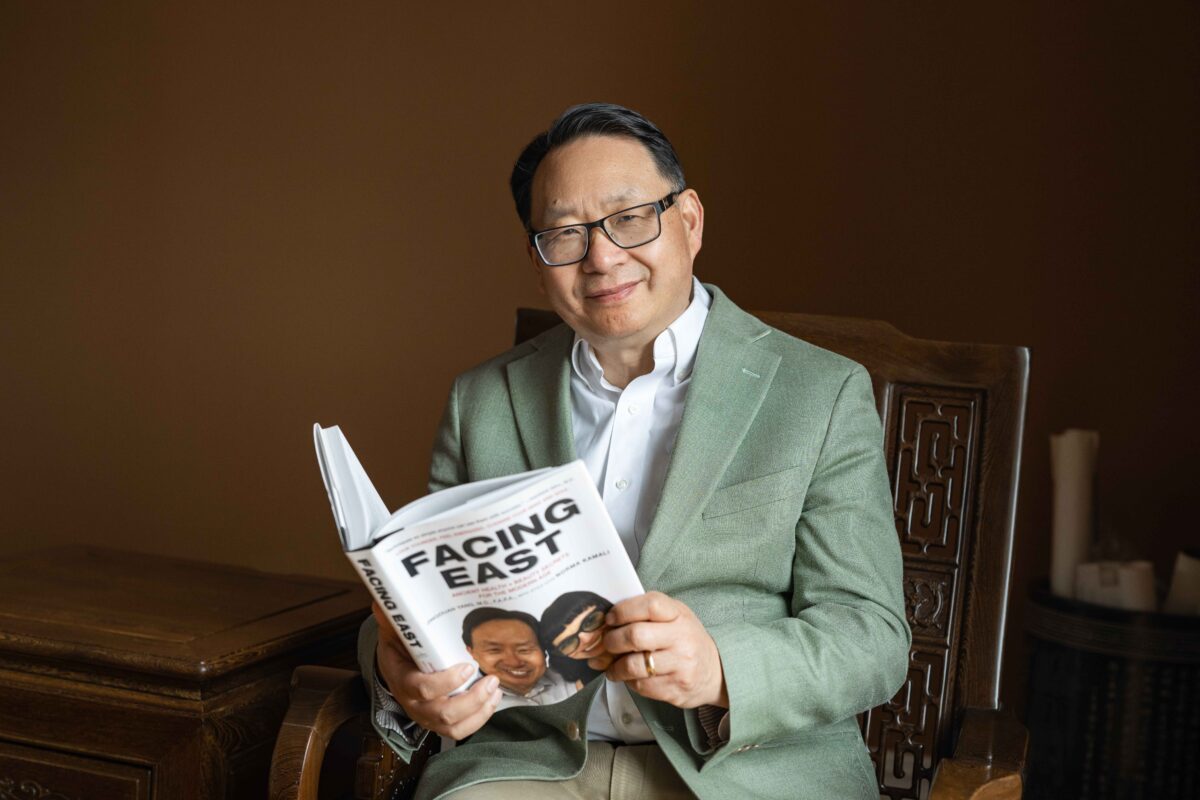

James Keyes, the newly minted CEO of the Fortune 500 company 7-Eleven, was bounding his way across the campus of Columbia University, en route to teach a business class at his Ivy League alma mater. He was nattily dressed in a newly tailored suit, briefcase in hand, daydreaming of past walks on campus.

Then, he was utterly gobsmacked. Walking toward him was a young student, arms wrapped around too many textbooks, his T-shirt preaching the gospel: “Education Is Freedom!” in bright, bold letters.

“I had an epiphany, right then and there,” Mr. Keyes recalled. “It was everything I had believed in and relied upon to get where I was to that day.” He vigorously shook the student’s hand and told him how much he agreed with the idea behind his T-shirt message. They spent a few minutes talking about how education had changed both of their lives. Mr. Keyes told the young man that he was impressed by his passion and vision and wished him well.

“He believed every word on his shirt. Thoroughly,” Mr. Keyes said. “I did too. I just hadn’t thought about it in those terms before.” He reflected on how Columbia and other educational opportunities had impacted his own life and provided him with the freedom to succeed. Back home in Dallas, Texas, he soon rallied like-minded business leaders, government officials, and entrepreneurs, and founded the Education is Freedom (EIF) charitable foundation. The year was 2002. These leaders envisioned a world where every young person could pursue a college education and a rewarding career. EIF would provide students with the tools needed to successfully graduate from high school, attend and graduate from college, and develop their career paths.

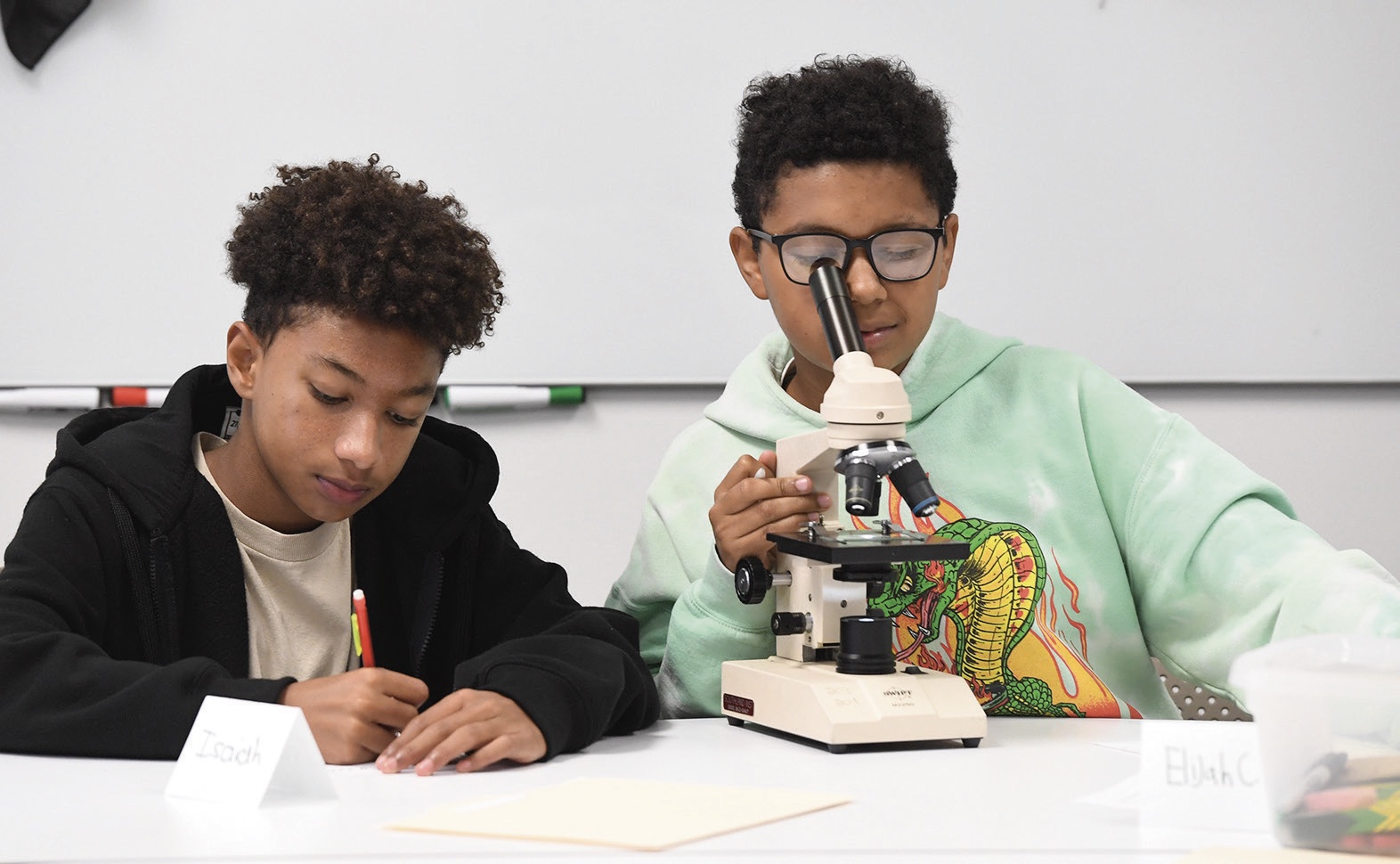

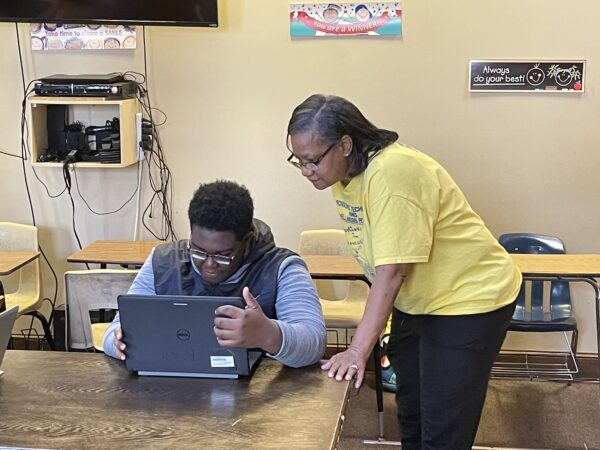

Over the past two decades, EIF mentors and counselors have helped more than 100,000 students and their families in multiple Texas school districts complete the college process. They’ve also provided scholarships to hard-working students. And they’re just getting started.

Now, Mr. Keyes has a new goal: to help heal and educate the entire world. In his new book released in February, “Education Is Freedom: The Future Is in Your Hands,” he outlines how the power of education can not only unlock our personal freedom and improve our individual lives, but is crucial to preserving our democracy. “Our country is so polarized right now,” he said. “We need more knowledge and less ideology. I believe that fear and ignorance are at the root of most of these issues. On both sides of the aisle.”

Whether it’s fear of the unknown; fear of the “other”; a mistrust of people and institutions; or fear of other cultures or religions—whatever it is, having the curiosity to learn will stomp out that fear. “It’s like when you were a kid in the dark and you were scared. And your mom came in and turned on the light and said, ‘See? No monster here,’” he said. “That’s what knowledge is. It’s the light that conquers fear.”

If we can encourage more people to turn on the light, we can reverse that cycle of ignorance, fear, violence, and anger that tortures the world, he argued. “Sounds a little Pollyannaish. But in so many ways, it is true.”

The Power of Education

Mr. Keyes argues that education can change the world. That’s because people gain the skills, tools, and opportunities to make better informed choices and decisions, he contends. They’re able to pursue their wildest dreams and aspirations and fully participate in the world around them. They can separate reality from fiction, confidence from fear.

One example he cites in his book is the story of Adan Gonzalez. Mr. Keyes first met him when he was a high school student living in South Oak Cliff, an underprivileged Dallas suburb. He lived in a one-room apartment with six other family members in a neighborhood where 32 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. During his sophomore year at Adamson High School, Mr. Gonzalez signed up for the Education is Freedom program on a lark. The program offered Mr. Gonzalez an internship at a local business to help him visualize a better future. “Unfortunately, he turned us down,” Mr. Keyes said. “He could make more money in a local factory. Like a lot of underserved kids, he went straight for the money.”

But in his junior year, Mr. Gonzalez reapplied and landed an internship at a local ad agency. The experience opened his eyes to new career possibilities. He aimed to attend Georgetown University and studied hard. Through grants and scholarships facilitated by EIF, as well as his academic rigor, Mr. Gonzalez got his Georgetown shot. He also channeled his love of fighting into boxing and became a national boxing champion while studying at Georgetown. “Instead of becoming a street fighter in South Oak, he became a college champion,” Mr. Keyes said. “What a story.”

After graduating in 2015, Mr. Gonzalez went back to his hometown grade school to teach math and social studies. He has since earned a master’s degree in education policy at Harvard and a master’s in education leadership at Columbia, and he has founded a nonprofit to provide underserved youth with academic support, leadership training, and community service opportunities. He recently received a White House fellowship, which he hopes can help him return home with the knowledge to improve his community’s education system.

“Adan is just a poster child for the idea that opportunity and education can transform anyone’s life,” Mr. Keyes said, adding that he’s moved by Mr. Gonzalez’s desire to work in the public school system. “He could have taken a much higher profile and higher paying job, but he’s really embraced that, for him, it’s about the freedom to do what he wants to. He has more freedom to give back to his community.”

His Life Story

Mr. Keyes himself has had his whole life transformed after working hard in school, though education wasn’t a priority during his hardscrabble childhood. Keyes was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1955, the youngest of six children. He grew up in a small, three-room shack without running water, plumbing, or heat. His parents, both factory workers, were highly intelligent but undereducated high school dropouts. Their impoverished life was difficult to bear. “Too many kids, not enough money,” he wistfully recalled.

His parents divorced when he was just five, and his mom “moved uptown to the trailer park,” he said. Keyes chose to stay with his dad. Though he lived in abject poverty, Keyes didn’t realize that his family was poor. His “rich” friends always came to his house to play because there were abandoned cars in the yard, tree swings, and creeks to play in. “I was poor but incredibly free and happy,” he said. “It wasn’t about wealth. We saw it as an adventure, like camping! I’ve remembered that all my life.”

But the family also endured hard times. When he was 10, his father was diagnosed with cancer, his grandmother fell ill and entered a nursing home, and their home was condemned by the local sheriff. Dad was sent to a veterans hospital, where he died six months later. Keyes went to live with his mother, who had to work two jobs to support them. “I lived through severe crisis after crisis,” he said. “So many horrible things [happened] before I was even 12 years old. It was then that I understood I had no safety net, no one to catch me if I stumbled or fell. It was up to me.”

At 15, Keyes began working for McDonald’s part-time and became the shift manager within a year. During summers, he worked a second shift as a produce truck driver, and he even made a side hustle out of being a church organist. “Hard work never goes out of style, and it pays off. I learned that early on, too,” he said.

With his earnings and a small baseball scholarship, he was able to attend the College of the Holy Cross. While there, his mother developed cancer, and he helped care for her. He continued working at McDonald’s. It was humble work, but it instilled his lifelong drive to outwork and outperform everybody. He would graduate cum laude with membership in the Phi Beta Kappa Honor Society.

He then attended Columbia Business School, where he learned the skills that would jump-start his business career. Mr. Keyes has a profound recognition and gratitude for how education led to his successes. “Education was the key that opened all my doors. It unlocked huge opportunities. It was my path to personal freedom,” he said. He believes that every American—every person, for that matter—needs to explore new interests throughout life.

He, for example, wanted to fly airplanes ever since the 1960s moon missions sparked a fascination with the skies. He learned to speak Japanese after working with Japanese business partners to bring 7-Eleven to Japan and wanting to overcome the language and cultural barrier.

His childhood experiences instilled a fierce sense of independence and an unbridled drive. His positive response to adversity—and his pursuit of knowledge and education—were the beginnings of a quintessential rags-to-riches American story.

He still remembers a poster that hung in the McDonald’s kitchen he worked at. “It still inspires me to this day. It had a famous quote from Calvin Coolidge.” The quote reads, in part: “Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Persistence and determination are omnipotent.” When he left that job, he asked the owner if he could take the poster with him, and the owner agreed. “I took it to shop class and burned the edges to dress it up. I’m looking at it right now. It’s hung in every office I have ever had,” he said.

After earning his MBA, he joined Gulf Oil and taught himself how to use an Apple computer—the most cutting-edge technology at the time—to streamline operations and replace clunky corporate spreadsheets. After steady promotions, he joined Southland Corporation, today known as 7-Eleven. In 2000, he was named president and CEO. After expanding the convenience store chain into a global brand, Mr. Keyes joined the ill-fated Blockbuster as CEO in 2007. He tried to shepherd in a digital streaming strategy, but money woes and market conditions eventually forced a sale of the company to DISH Network.

Despite setbacks, Mr. Keyes remains highly regarded as a visionary industry tycoon. His days as a CEO taught him one crucial lesson that he also shares in his book. “Yes, it means Chief Executive Officer,” he said. “But more importantly, it means ‘Change Equals Opportunity.’” If you’re knowledgeable, persistent, and dedicated to your passion, you will embrace change not as a negative but as a tremendous opportunity, he concluded. It’s a trait that is necessary for survival in and out of the boardroom.

A Promising Future

Keyes believes that the American dream is still alive and well. “Arguably it’s more alive than ever before in history,” he said. “That’s because of the emergence of technology. Truly and literally, the future is in our hands. There’s no excuse now. Everyone can have access to unlimited learning. The cell phone itself is a portal to unlimited learning.”

He expressed optimism about how technology can revolutionize education, citing how the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated access to technology and educational resources as schools embraced remote learning. He’s buoyed by the future possibilities. “I want to see a future where academic content is as engaging as video games and where students are incentivized for their learning progress—where tech can tailor to individual needs, providing flexibility,” he said. He hopes such technology can supplement classroom learning and inspire people to become lifelong learners.

“Someone can take your money, your material things, your job, … but they can’t take away what you know. My dad told me that,” he said. “With knowledge, you can replace anything lost, you can be free to explore the world, you are beholden to no one. That’s the path to real freedom.”

The Three C’s

James Keyes defines the Three C’s that have helped him weather challenges, especially during his business career.

Change is inevitable in life, Mr. Keyes asserts. Both 7-Eleven and Blockbuster went through drastic changes during his tenure, and he had to respond—whether it involved restructuring the business or redefining the way the companies delivered and sourced products.

“You have to accept and respond to change, especially in the face of adversity,” he said. “You can’t give up or become a victim in the face of challenges. You must see the learning opportunities that come with change.”

Confidence is essential to responding to such changes. When going through turbulent times, people have a tendency to let fear take over, such as fear of losing one’s job or fear of people thinking negatively of one.

“You must have confidence in your own skills and abilities,” he said. “You must keep your head up and confidently look to the future.”

Clarity is the ability to break down complex problems into their simple components. It prevents one from being overwhelmed and better facilitates learning, according to Mr. Keyes. During times of crisis, keeping things simple is vitally important. “It’s how you navigate to safe harbors,” he said.

From July Issue, Volume IV