Nate Brown’s deep appreciation for the Pacific Northwest stems from a four-day road trip across the Olympic Peninsula in 2013, during which he surveyed snow-capped mountains and lush forests nestled between the coastlines. An Army mission had brought Brown there, and he was captivated by the landscape that stood before him. After retiring from the Army in 2018, he made it his mission to fully explore the Olympic Mountains by climbing 30 summits within a period of just three years. In September 2021, after hiking over 500 miles and climbing an astonishing 160,000 feet, he achieved just that.

While serving in the Army, Brown had set foot in almost every corner of the United States but had not traversed the Pacific Northwest. So after a break from active duty, he decided to re-enlist under the condition that he be placed in Washington. Stationed at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, southwest of Tacoma, Washington, Brown was blown away by the natural beauty of the mountainous terrain. When his mission ended in March 2018, he was ordered to leave his base and serve at a different location—but he politely declined. After 13 years of service, Brown deemed it time to spend the rest of his life in the picturesque Pacific Northwest. Since then, Brown has adopted Washington as his chosen home with no plans to ever leave.

A Passion for Mountaineering

While in the Army in 2015, Brown was trained in technical alpine climbing by The Mountaineers—a nonprofit community on a mission to share knowledge and encourage others to partake in outdoor activities such as alpine climbing, mountaineering, wilderness navigation, sea kayaking, and snowshoeing. Brown’s class lasted for about six months and took place in the evenings at the community center. Students learned technical alpine climbing theory before going down to Mount Rainier for a few weekends a month to put their knowledge to the test.

The most important thing Brown learned was that in order to improve in technical alpine climbing, he needed to find a core group of climbing partners whom he trusted. An individual’s fitness level is important to take into consideration. According to Brown, finding someone with approximately the same fitness level is best, so nobody struggles to keep up during a climb. Another key factor is having good judgment: many people encounter “summit fever” and become adamant about reaching the top regardless of conditions. That mentality presents many hazards, not just for the individual but for the entire group. Lastly, remaining humble is key. As Brown explained, “no matter how much you know and how good you are when you are in a contest between you and the mountains, the mountains will always win.”

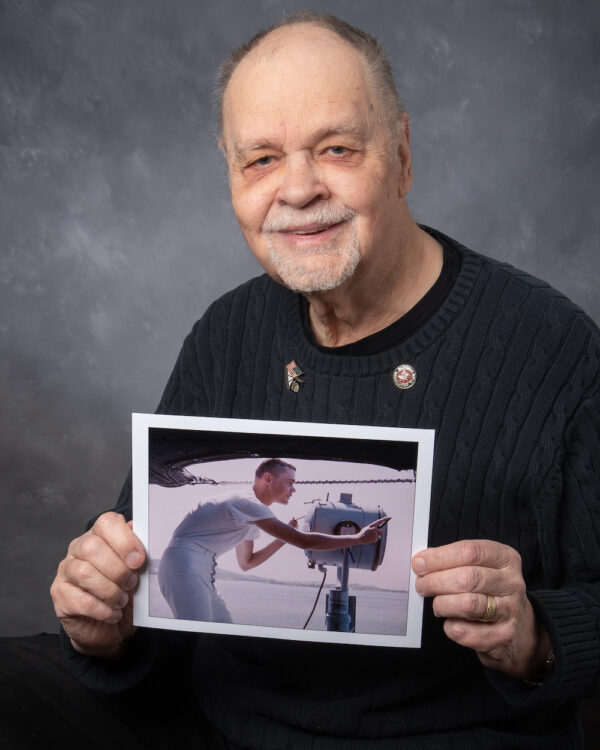

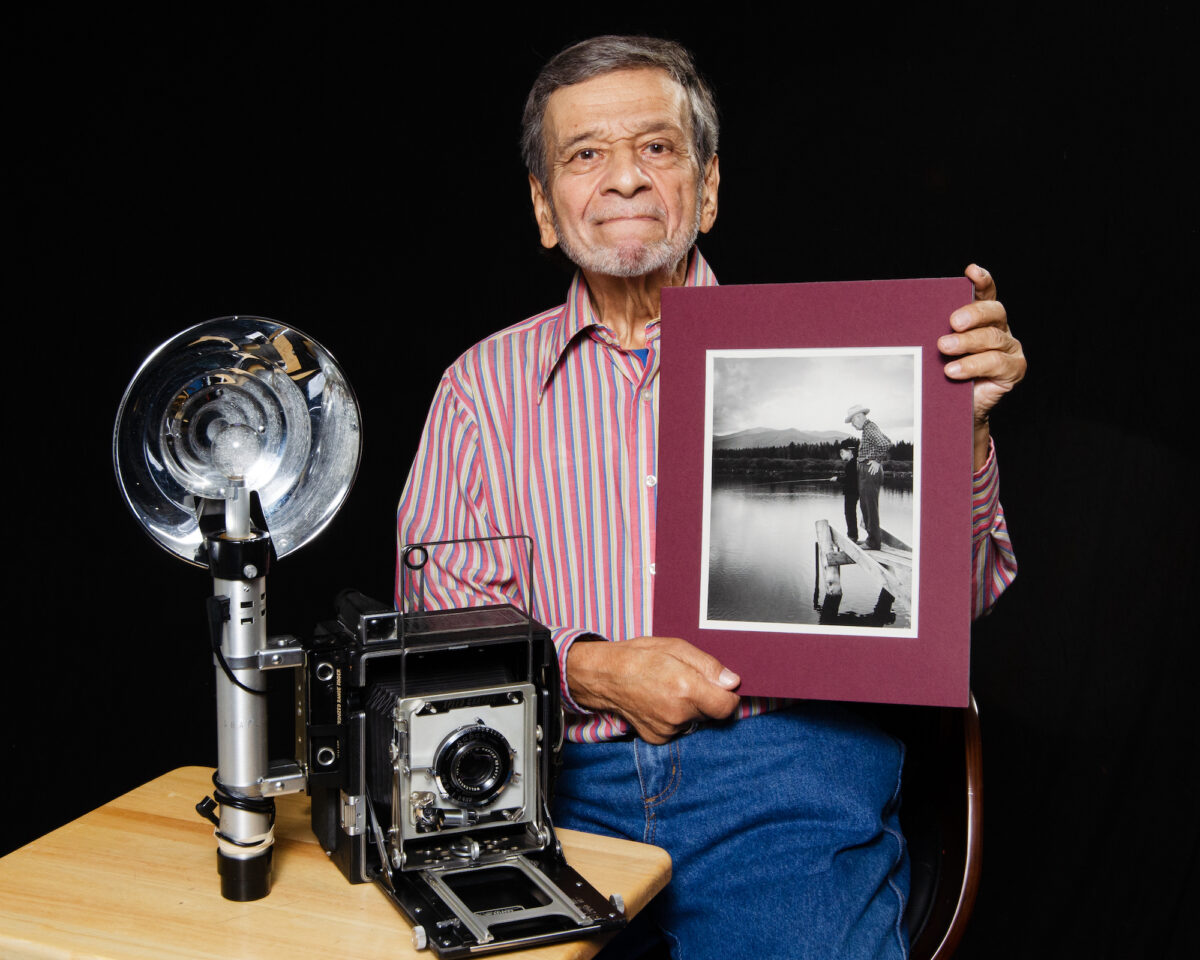

While still on active duty, he discovered Veterans Expeditions, a Colorado-based organization that encourages veterans to explore the outdoors. “They [the group] would come to the Pacific Northwest every now and then and climb mountains, like Mount Rainier and Mount Hood,” he said. One day, Brown reached out and offered to accompany them as a photographer on their trips, taking pictures of veterans that they could keep or give to sponsors. So Brown connected with the group and started climbing peaks with them—as “the guy in the background with the camera,” he laughed.

After a year or two, Brown was asked whether he would be interested in leading some trips of his own, as he was more experienced in mountain climbing. So in 2020, Brown led a three-part volcano climb series involving beginner-friendly treks to Mount St. Helens, Mount Adams, and Mount Hood. He and two other experienced mountaineers assumed leadership of groups of eight veterans each. The entire expedition lasted a few months, and the leaders taught veterans important skills like how to use ice axes and wear crampons (metal traction devices that attach to shoes, improving snow mobility).

The Olympic Mountain Project

In May 2019, Brown decided to embark on a new endeavor. A friend asked him what his favorite place in Washington was, and Brown instantly replied the Olympic Mountains. But as they sat down and peered at a giant folding map of Washington, Brown observed that though he claimed it as his favorite place, he hadn’t ever fully explored the Olympic Peninsula. “I realized I had really only been on the outside edges—because the Olympic Mountains are a circular cluster,” he explained. “I should climb enough mountains spread out throughout the entire Olympic complex to say without a shadow of a doubt, I have seen the Olympics.” He immediately started planning his project. He set out to explore 30 mountains, not only from the outer edges but also from the hard-to-reach interior areas.

Through the expedition, Brown, who has a full-time job working for a federal government agency, also hoped to raise awareness of the issues facing the Olympics, including underfunding and climate change, by partnering with Washington’s National Park Fund (the official philanthropic partner of the three major Washington National Parks including Olympic National Park) and donating 25 percent of the profits from selling his photo prints to the organization. He wanted to use those funds to support the organization in keeping the parks open for all to enjoy.

Planning such an extensive project was no easy feat; Brown admitted that he spent more time researching than actually climbing the mountains—as the inner mountain peaks were relatively uncharted. Of the 30 peaks he would climb, only four of them had trails leading to the top. Brown had to research the rest and plan for unexpected obstacles as much as possible, hoping to ensure safe paths through the wilderness. After many hours and days poring over various maps of the Olympics, he finally mastered the layout of the mountains. “I don’t even have to reference a map anymore. I have it memorized,” said Brown.

Cruising Through Rocky Paths

In 2020, Brown was hit with an unforeseen predicament: the pandemic. National parks faced extended closures from April to July, due to measures set forth by the Washington governor. According to Brown, those months are considered prime climbing season; as some of the snow has melted, travel is easier and the risk of avalanches is low. During that time, he also had difficulty convincing climbing partners to join him on his trips, which sometimes required hiking 60 miles just to climb one peak. As a result, he went on several trips by himself. Brown’s drive to achieve his goal of exploring the Olympics was the fundamental factor that led him to continue his great expedition. “This is my favorite place in the entire world, and I’m going to see the whole thing. I just needed to see it through,” he said.

Mountain climbers often travel in groups for safety. On his trek up Mount Olympus, Brown was accompanied by six of his friends, and together they formed glacier rope teams. A six-person team is the standard for safe glacier travel, Brown explained. “If you had two ropes, each rope would have three people on it—then you can get yourself out of any tough situation,” said Brown.

His mountaineering project lasted for nearly three years, during which time Brown encountered much wildlife, including black bears, elk, and marmots. “I encountered so many bears that I would come to be completely numb to them,” he laughed. He explained that there are mostly black bears in the Olympics, which are often less aggressive than grizzly bears. He also photographed pikas in the Cascade Mountains. Brown said that he even spotted paw prints belonging to mountain lions, though he never saw one in the flesh.

When he’s not climbing mountains, Brown is often seen, camera in hand, capturing the beautiful landscapes of the Pacific Northwest. He admits that on any given trip, he shoots a minimum of 300 photos. On longer trips, it’s not unusual for him to return with upwards of 1,000 photos. The pandemic has allowed Brown ample time to revisit images and reflect on the memories and places he captured. Through this, he discovered photos he had previously overlooked.

The 30 Peaks

The path to success is seldom smooth, and Brown learned that there are many unforeseen obstacles even after extensive planning. Bodies of water are typically represented on maps by squiggly blue lines, but one never truly knows whether those might represent a creek, a two-foot water ditch, or a raging river, Brown admitted. The seasons also play a big part in the depth and intensity of water features, with spring bringing increased water flow compared to fall when water tends to evaporate more quickly. “There were several times where I got to a point where I had to cross this body of water and there was no safe way to do it,” said Brown. He would have to turn around and reevaluate his plan, or completely remove a peak from his list and replace it with another one. “That was a benefit of choosing my own peaks—I got to move the pieces around as I thought fit,” he said.

Upon visiting certain peaks in the summer and revisiting them in the colder months, Brown noticed striking differences in appearance and captured them through photos. A mountain slope usually covered in bushes, shrubs, and small trees would appear entirely flat in winter, buried under a thick blanket of snow. The few trees that remained uncovered would take on different shapes, blown by icy gusts and frozen in place.

Brown carefully handpicked the 30 peaks, making sure they spanned the entirety of the Olympics, but he had to consider many factors to make the expedition achievable. He said that the Olympic Mountains are known for having brittle, crumbly rock composed of ancient seafloor, so the danger of rockfall is always imminent, especially during vertical climbs. Whenever possible, Brown and company would climb side-by-side, so no one would be in front of another. The few times when this wasn’t an option, whoever was behind would hide in a cubby, or hole, while the person in front climbed up, stopped, and gave the all-clear. Communication was very important in those instances; otherwise, said Brown, one might send rocks flying down onto the person below.

In early September 2021, Brown concluded his expedition by climbing Mount Steel. As he stood at the summit over 6,000 feet above, the sun rose from behind the distant mountains and thick clouds swirled down below. “I stood eye to eye with each of the peaks I had climbed previously. It felt as though they were all standing in silent unison, giving me this one last moment to forget about everything below. One last morning where for a moment, nothing else existed; just me and the Olympic Mountains I have spent so much time in,” Brown wrote in a Facebook post. He scanned the horizon, naming and thanking each peak for seeing him safely up and down its jagged slopes. After climbing over 160,000 feet and traversing 500 miles, Brown had safely and proudly made it to the finish line. He felt relief and gratitude. Although the adventure ended, Brown would never forget his time in the Olympic Mountains, and the photos he captured during his journey would remain a testament to his accomplishments.