During the pandemic, when we were denied access to the world and were left only with our personal spaces—our homes, our backyards, at most our neighborhoods—photographer Joel Sartore, recipient of this year’s Indianapolis Prize Jane Alexander Global Wildlife Ambassador Award, found some comfort in the fact that people were finally finding joy in the small things.

Undistracted by big jobs, big journeys, or big plans, people started focusing on their inner lives, their families, and their communities. Some took up gardening, bird-watching, or drawing. They saw the detail, they appreciated the quiet. They seemed to have grasped that the small things in life mattered hugely. For a while, at least, they gave the small things the recognition they deserved.

Mr. Sartore was pleased to see this because, for more than a decade and a half, he had been beating the drum for the tiny creatures we rarely find the time to notice. “I’m the person who captures the insects and amphibians, the mollusks and minnows, and all the other creatures that get no airtime in debates about the catastrophic extinctions that are happening on our planet. I hope my photographs give a voice to the flying, crawling, swimming, walking, wading, breathing beings that live and die unseen and unheard.”

A Mammoth Task

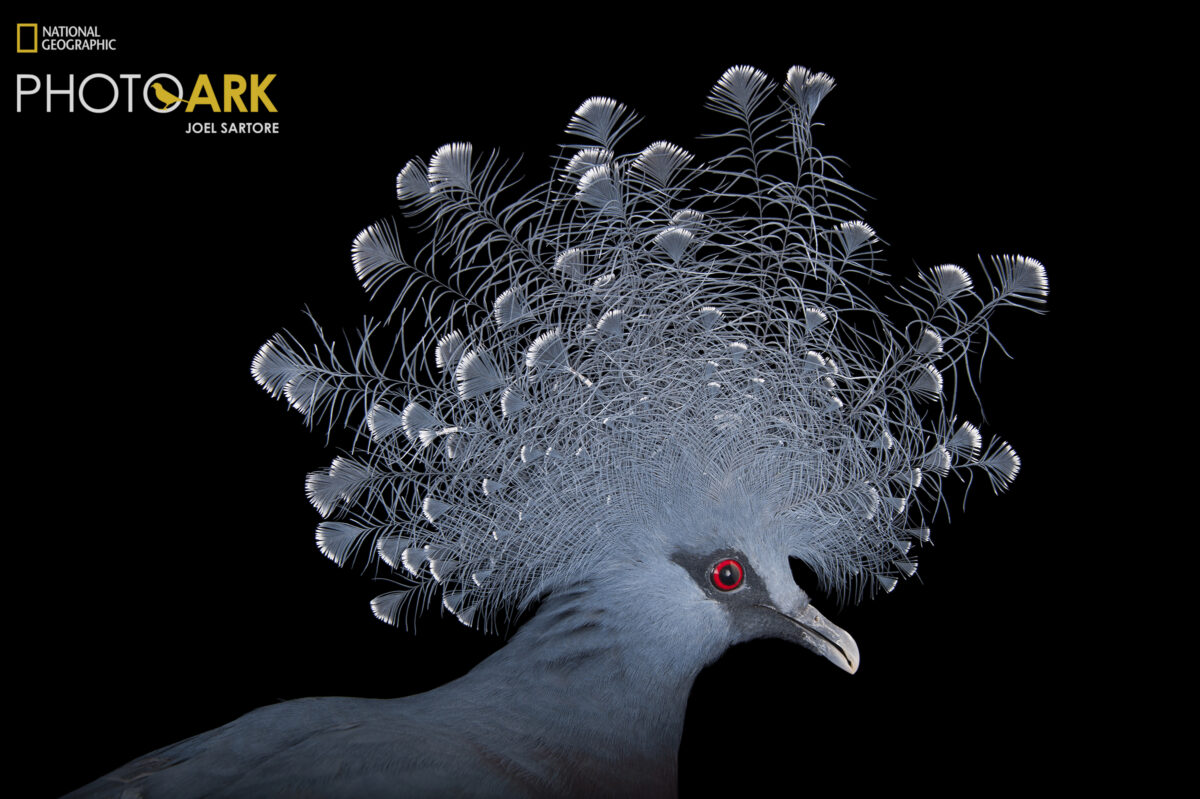

In truth, Mr. Sartore, a career photographer who has won the world’s largest prize honoring animal conservation efforts, is in the process of photographing all manner of animals—great and small—for his remarkable National Geographic Photo Ark project. His plan is to eventually document every species in human care—that is, in zoos, sanctuaries, aquariums and the like—as a way of highlighting what we stand to lose if we do not wake up to the damage we are doing to our planet. As of the time of writing, he has documented 14,702 out of an estimated 25,000 in human care, and he has no intention of stopping. “The fact is, we actually don’t know how many species there are,” he said, “but if we do not change our behaviors, there will certainly be far, far fewer by the end of the century.” The Photo Ark is his way of trying to prevent that catastrophe from happening. “We are destroying oceans, prairies, marshes, forests, and in doing so, we are making so many animals extinct. Just wiping them out. We ignore their loss at our peril.”

Mr. Sartore draws an excellent analogy to illustrate his point that every species we drive to extinction brings us one step closer to our own destruction. “Our ecosystem is like a beautifully balanced Jenga tower. Removing even a single piece could destabilize it. And yet here we are, taking out one block after another. If we don’t stop, we’ll reach the tipping point, after which—well, after which, the whole lot will come crashing down, taking us down with it.”

Close Encounters, of the Wild Kind

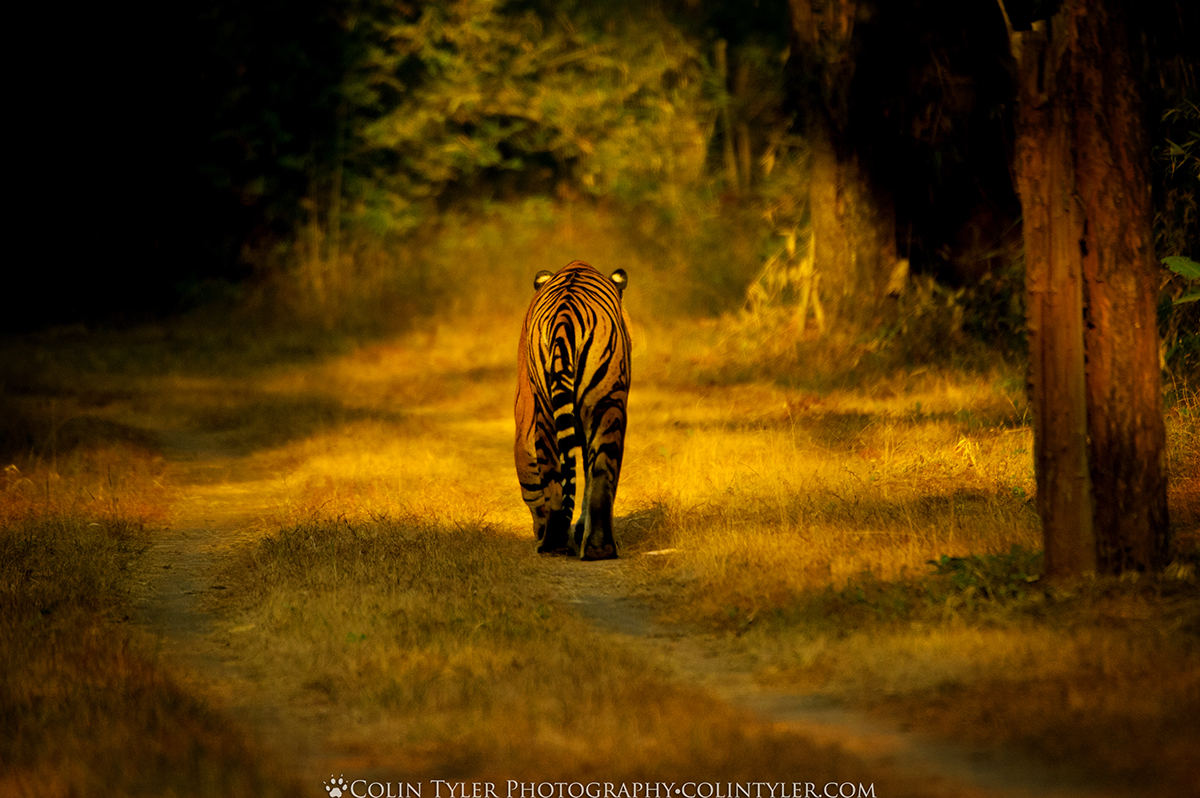

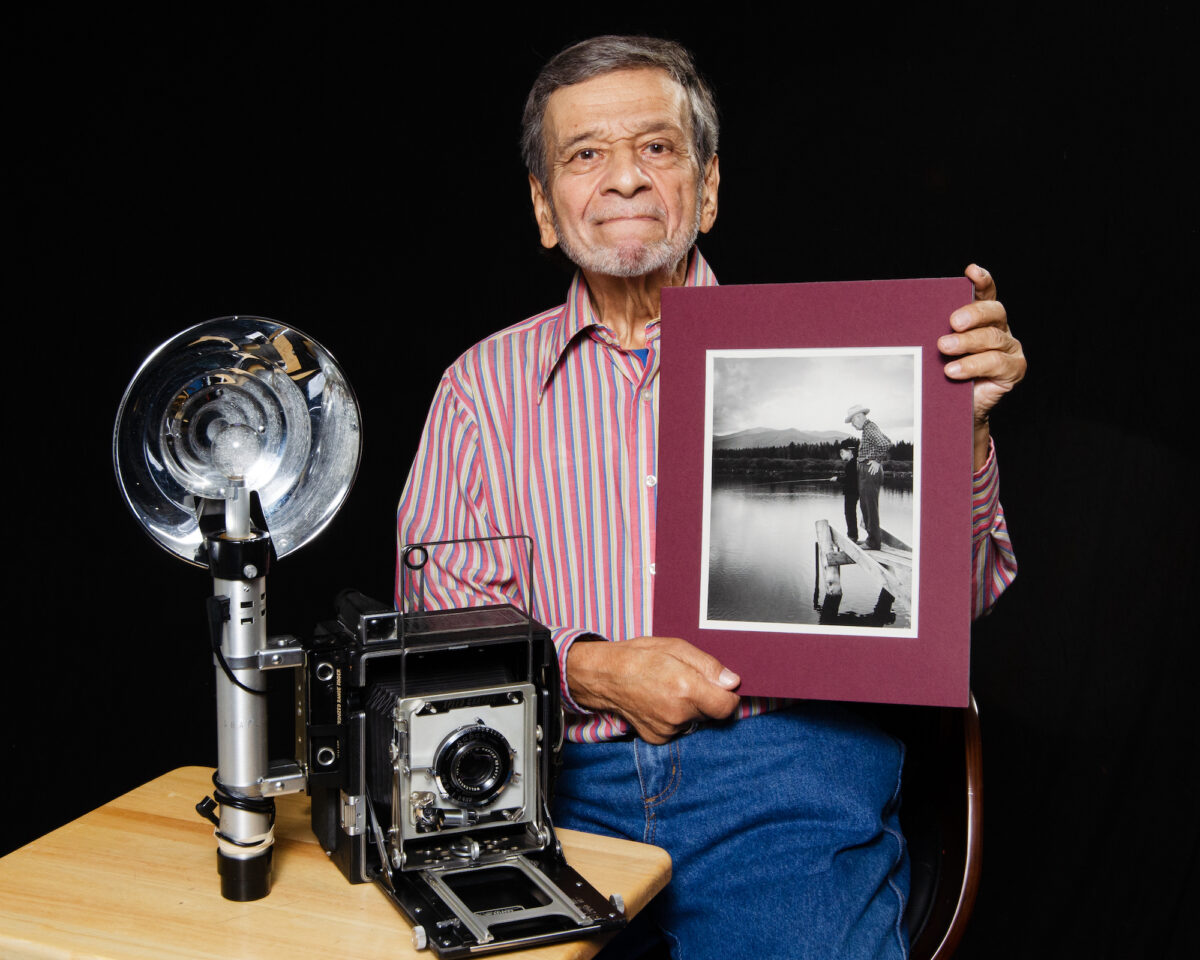

He started the Photo Ark in 2006, after his wife, Kathy, was diagnosed with breast cancer. Before that, he’d been out in the field almost constantly on assignments for National Geographic, traveling from pole to pole, from sunrise to sunset, in freezing temperatures and baking ones. He has a talent for taking once-seen, never-forgotten images: shots that sear themselves onto the mind and which inspire wonder at the sheer miracle of nature. It’s impossible to grow tired of looking at the spellbinding picture of a golden lion, high in a tree, all aglow against a midnight sky; or a bloodied polar bear, peering through the window of Mr. Sartore’s truck, minutes after having put its face into what remained of a whale carcass. And then there is the extraordinary shot of a grizzly bear, jaws flung wide open in anticipation as a salmon flies straight toward it.

In others, it is the interaction between him and the animals that arrests. Butterflies dance on his face, mosquitoes drain his feet of blood, walruses bask alongside him as he snatches a nap. Each one has a story; each one is a story. “Ah, the mosquito one—that was something. It was taken on the North Slope of Alaska, an area renowned for its mosquitoes. I’d been there for a few days, but wasn’t thrilled with anything I’d done, so I took off my shoes and socks and let them at me for about 20 minutes. I can still hear the noise of them—crackling, taking their fill. I scratched my feet raw, but I got one of the most talked-about pictures of my career.”

He’s also been charged by grizzly bears and musk oxen, been pooped on by Marburg virus-carrying fruit bats in Uganda, and survived leishmaniasis, which he developed after being bitten by a parasite-infected sandfly in Bolivia. The infection spread to his lymph system, destroying the flesh on his leg. It took surgery and chemotherapy to help him beat it.

None of this deterred him from shooting out in the wild. It was only his wife’s illness that grounded him, literally and metaphorically. “I wanted to stay home in Nebraska with Kathy,” he said. “Even after she recovered, I decided the time had come to draw a line under my field work. My focus had changed, plus I realized that the big picture—creating compelling images that might encourage people to consider the impact of their actions on wildlife—might be served by the small picture, that is, a portrait of an animal, with captions that told you all about it, and whether it was in danger or not.”

Animal Close-Ups

Each creature is photographed against a stark black or white background, and, whenever possible, looking out at the viewer. Eye contact is key, said Mr. Sartore. “It brings immediacy, it brings intimacy, it brings empathy. I hope it brings understanding and awareness.”

In some cases, people are looking straight into the abyss of extinction. In 2015, he photographed Nabire, a northern white rhino, at Safari Park Dvur Kralove, in the Czech Republic. She died one week later, which means there are now only two of her species—both females—left. Mr. Sartore tries to keep his emotions under control when working, but he admits that photographing Nabire was profoundly moving. “I felt I owed her an apology, on behalf of the human race,” he said.

As such an impassioned animal lover and conservationist, does he feel in any way conflicted or saddened about seeing and photographing animals in zoos? “No, not at all. Zoos and sanctuaries preserve and conserve species, and they aim to educate millions of visitors every year.”

It was on trips to the zoo with his parents as a child that his passion for wildlife began. “Those visits, and the books we read as a family, shaped my path. I remember finding out about the extinction of the passenger pigeon, and feeling so sad that that had been allowed to happen. And yet here we are, all these decades later, still losing species. I hope people will look at all the animals in the [Photo] Ark, from the largest to the tiniest and from the ones we coo over to the ones that we recoil from and realize that they all have their place in the world, and that humankind should do its best to protect them all.”

What We Can Do To Help

If there is one message Joel Sartore would like to communicate, it is that each and every one of us can do something to help preserve our planet’s incredible diversity. Here are five foundational tips he says we can all follow:

1. Consume less. Whether it’s food, clothing, water, or utilities, try to reduce your usage. Buy from thrift stores, swap clothes and books with friends, and shave 30 seconds off the time you spend in the shower. Tiny changes to your daily routine will have a big impact.

2. Think before you eat. Cutting down on meat is good for your own health as well as that of the planet, but try to make informed choices about the rest of your groceries. Many processed food products contain palm oil. Conversion of tropical forests to oil palm plantations devastates plants and animal species and increases human-wildlife conflict as animal populations have their natural habitats destroyed.

3. Flick the switch or unplug your electrical equipment and devices when you’re not using them.

4. Ditch single-use plastic. Always pack your water bottle and coffee cup with you, and avoid products that come in plastic, such as potato chips. Try to save any plastics you have accumulated and take them to a recycling point if your curb-side collection doesn’t include them.

5. Quit pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. Plant nectar-bearing plants and milkweed to attract monarch butterflies and other insects. Let parts of your garden go wild. You might be amazed at the creatures that move in.

From Oct. Issue, Volume 3