You might think that actor Steve Guttenberg, known for the role of Mahoney in the “Police Academy” movies—a character who once gave a speech with his fly unzipped—would find just about everything a source of hilarity. But there’s one thing at least that he is dead serious about: honoring his mother and father.

Guttenberg honors them with a passion that informs his new book, “Time to Thank: Caregiving for My Hero.” A series of vignettes that alternate memories of growing up with reminiscences of his adult life, it’s a history of the journey Guttenberg took from humble beginnings to superstardom—an all-American success story that led him from his family’s small apartment in the Flushing neighborhood of Queens to Hollywood fame.

It’s all seen through the lens of his father’s last years, when Guttenberg commuted regularly from California to his parents’ home in Arizona to assist with dialysis treatment, which extended his dad’s life for several years.

“Time to Thank” is a portrait of a son’s devotion to his family and, before that, the story of a family’s devotion to their son.

Heading to Hollywood

Guttenberg’s father, Stanley, was a New York cop and Korean War veteran who believed in his family with absolute faith. Self-reliance was a trait that he, as a father, exhibited and encouraged in his children. When Guttenberg, at only 17 and fresh out of high school, expressed the desire to leave New York for Los Angeles to plunge himself into the movie business, many, if not most, parents would have said no.

Guttenberg’s parents practically helped him pack his bags. He recounts in “Time to Thank”:

“When I first came to Hollywood, my parents gave me two weeks and $300. They believed that, in my youthful endeavor, I could be trusted. Their hope for a measure of maturity meant that I could do what I dared to; my parents intended the cash for food and gasoline to shepherd me around Tinseltown.

“I spent almost the whole shebang on photos of myself.”

The first attempt at transplanting to Hollywood failed, despite some limited success, and Guttenberg returned to the East Coast and college. But in Hollywood, he had employed an agent, and, one day, out of the blue, that agent called him with the perfect part in a major new film.

Guttenberg’s portrayal of the young Nazi-hunter in “The Boys from Brazil” (1978) was his breakthrough role at the age of 20. Co-stars included Gregory Peck, James Mason, and Sir Laurence Olivier. He found Peck especially impressive.

“Greg was so generous, so thoughtful, and really good to me in so many ways,” Guttenberg recalls in a phone interview with American Essence.

“I was blown away by his ease and his greatness. When you’re around someone who does their job really well—a great baseball player, a great chef, a great director, a great architect—they’re very easy to be around, very down-to-earth. Their greatness makes them focused. They’re not distracted.”

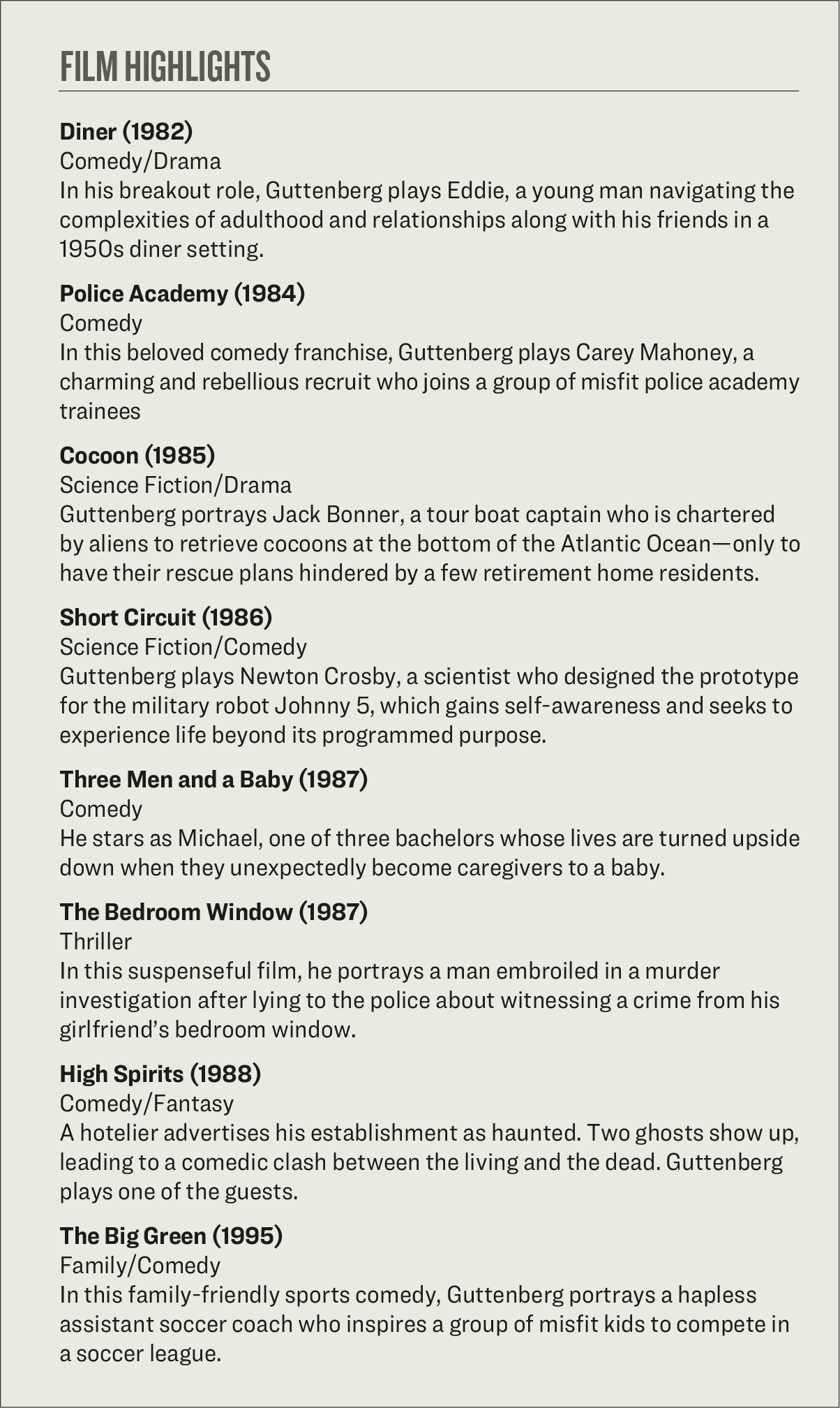

A dozen films followed in rapid succession, among them the highly respected and successful “Diner” (1982), “Cocoon” (1985), and “Three Men and a Baby” (1987). Among these came the four “Police Academy” flicks (1984–1987), slickly spoofy movies that have been described as broad, silly, goofy, feel-good, and flat-out dumb. The franchise didn’t win any prestigious awards, but did it soar at the box office!

Its popularity linked Guttenberg with “Police Academy” and the character of Mahoney forever. The association was so strong that when he met famous Italian film producer Dino de Laurentiis in connection with his appearance in the de Laurentiis film “The Bedroom Window” (1987), the producer greeted him with, “Ah, ‘Polizia Accademia!’”

Guttenberg embraces the fame he won through the “Police Academy” movies, but he also points out the range of his other films.

“I’m very lucky that so many of my films appeal to people in different ways. Some people come up to me and say, ‘Can’t Stop the Music’ is one of the best experiences of my life.” (“Can’t Stop the Music” was a wild, extended music-video-as-film from 1980.) “Other people say that ‘To Race the Wind,’ a movie I did early on about the first blind law student at Harvard, speaks to them. ‘Three Men and a Baby’ really addressed the single parent phenomenon.

“And yes, some people will say that ‘Police Academy’ saved their life. Bill Clinton said that when he was having a hard time in the White House, he and his daughter Chelsea would sit in the screening room of the White House and watch ‘Police Academy.’”

The greatest compliment of all came from a legendary funny man.

“Woody Allen once told me ‘Police Academy’ made him laugh,” Guttenberg says.

Family First

Guttenberg’s parents did not get lost along their son’s yellow brick road to stardom. His dad especially liked to visit Guttenberg on set from time to time. The stories are outrageous and plentiful. There was the time when his dad said yes to performing a stunt on a set overseen by fabled director Blake Edwards. Moments before the stunt, who should show up but Dame Julie Andrews, Edwards’s wife and one of Stanley Guttenberg’s idols. As he did the stunt—a 50-foot jump into an airbag—the elder Guttenberg yelled, “This is for you, Miss von Trapp!” The reference was to Andrews’s character in “The Sound of Music.”

Dad also pulled his son out of some tight spots. There was the time Guttenberg ran out of gas on his way to Arizona and found shelter from the heat in an abandoned building. Little did he know he was trespassing, and, when a state trooper arrested him, there seemed no way to avoid a night or two in jail.

Then, like a miracle, his dad called. The trooper wouldn’t allow Guttenberg to answer the phone, but he answered it himself and was soon in conversation with a fellow cop from back East. Before you could say “fellow officer,” Guttenberg was free.

“The CEO of Facebook could not have saved me from arrest, but my dad did. He saved me in all kinds of ways. He saves me every day—even now. The second I wake up, I ask him to tell me something. Today, he said, ‘Have a great attitude and you’re going to move forward.’”

After Guttenberg’s dad passed away, he understandably had a hard time dealing with it. When a friend suggested writing a book about the endless trips back and forth to help his dad with his dialysis, about his family’s mutual devotion, and the amazing things that happened around his dad, such as the incident with the state trooper, Guttenberg took on the challenge.

“People asked me if it was cathartic. No. It was painful. Only now that the book is published am I starting to get a lot better at accepting it.”

Guttenberg’s easygoing personality comes across in the book. “I get along with pretty much everybody,” he says. “I can get along with a Gila monster.” Which is fortunate, given all those times he crossed the Arizona desert to administer the dialysis, sometimes with the assistance of his sister Susan or his wife Emily.

Because so many of his hit films were made when he was in his 20s and 30s, we think of Guttenberg as perennially young. But he is now in his 60s and playing age-appropriate roles. He’s currently shooting a family film called “American Summer.”

“It’s a coming-of-age film about a 14-year-old boy. I play him as an adult.” It’s all about growing up.

How would this good son sum up the philosophy of his wise father?

He thinks for a minute or so. Then he says: “Get up out of bed. Don’t lie there. Wake up and open your eyes. Don’t think, don’t ruminate. Get up out of bed and everything will turn out great.”

+++

Wisdom From The Gute

In his Instagram bio, Steve Guttenberg describes himself as an “actor, writer, sandwich maker,” but he’s also known for his uplifting words. Here are some pearls of wisdom:

In his Instagram bio, Steve Guttenberg describes himself as an “actor, writer, sandwich maker,” but he’s also known for his uplifting words. Here are some pearls of wisdom:

- There are times in everyone’s lives when you kind of wonder if anything really is possible. Can you achieve certain things? Can you make things happen? Can you do what you’ve been told is impossible? So there are times in my life when I think “that’s impossible,” but maybe it’s not impossible. Maybe whatever you can do, you can do.

- You are never alone. Whether you have family or friends, people that you know and love and care about, that care about you, somebody you see on the street every day—you’re just never alone. We all feel alone sometimes, but you’re not alone. You’re never alone.

- I never wanted to get up early when I was younger. Now I love it. It’s exciting! It’s exciting to start the day before anybody else is around. It’s a good time to think about my life—about the people I love and the people that love me, the people I care about, the people that care about me. And how I want to contribute. What do I want to give today? What do I want to give? What do I want to put out there that makes this world a better place? I want to think about what I can give today.

- I go to all these places I know, but sometimes you gotta go somewhere you don’t know and learn something new. See new sights, something different. Get out of your comfort zone.

- Today, I’m thinking about being grateful. Being grateful for my life, the people that are in my life, the things I do, the things I get to do, the things I’m going to do, the things I’ve done. I’m really thinking about being grateful. There are often times—many times, I don’t know about you—where I forget to be grateful. So today, I’m really working on being grateful.

- Just a lesson to myself: I can get myself out of a lousy mood. Maybe you’ve got the same feeling, too. You can get yourself out of a lousy mood just by saying, “No. Things are OK.”

- You know what? You’ve got to make the effort. You want to become somebody? You gotta make the effort. You want to go somewhere, you want to visit a friend, you want to have a meeting? You have to make the effort. Nothing happens at home.

- I’ve been thinking about the journey, and thinking that my dad would always say to me, ‘It’s up and down.’ It’s like, kind of like a rollercoaster. You’ve got your great days, and you’ve got your days that don’t work. I’ve definitely had my share of hard times that challenged me, and I think I learned some lessons. There are also those highs, where you win, and everything is just going great. It’s a journey. So, let’s just take every step.