The Mark Twain House & Museum resides befittingly in Hartford, Connecticut, in the charming, historic neighborhood of Nook Farm, once a thriving artistic community. The lovingly preserved home of America’s humorist was built in an American Gothic Revival style in 1874 and was lived in by Twain and his family until 1891.

The mansion was intended to make a statement about its owner and his burgeoning literary career. Its whimsy, elegance, and extravagance—from exterior painted bricks, exuberant gables, and tiled roof, to the elaborate interior decorations—made a definitive statement in the 19th century. Indeed, the Gilded Age look of Twain’s home, with its layered, maximalist design of furnishings, textiles, and patterns, is once again in vogue.

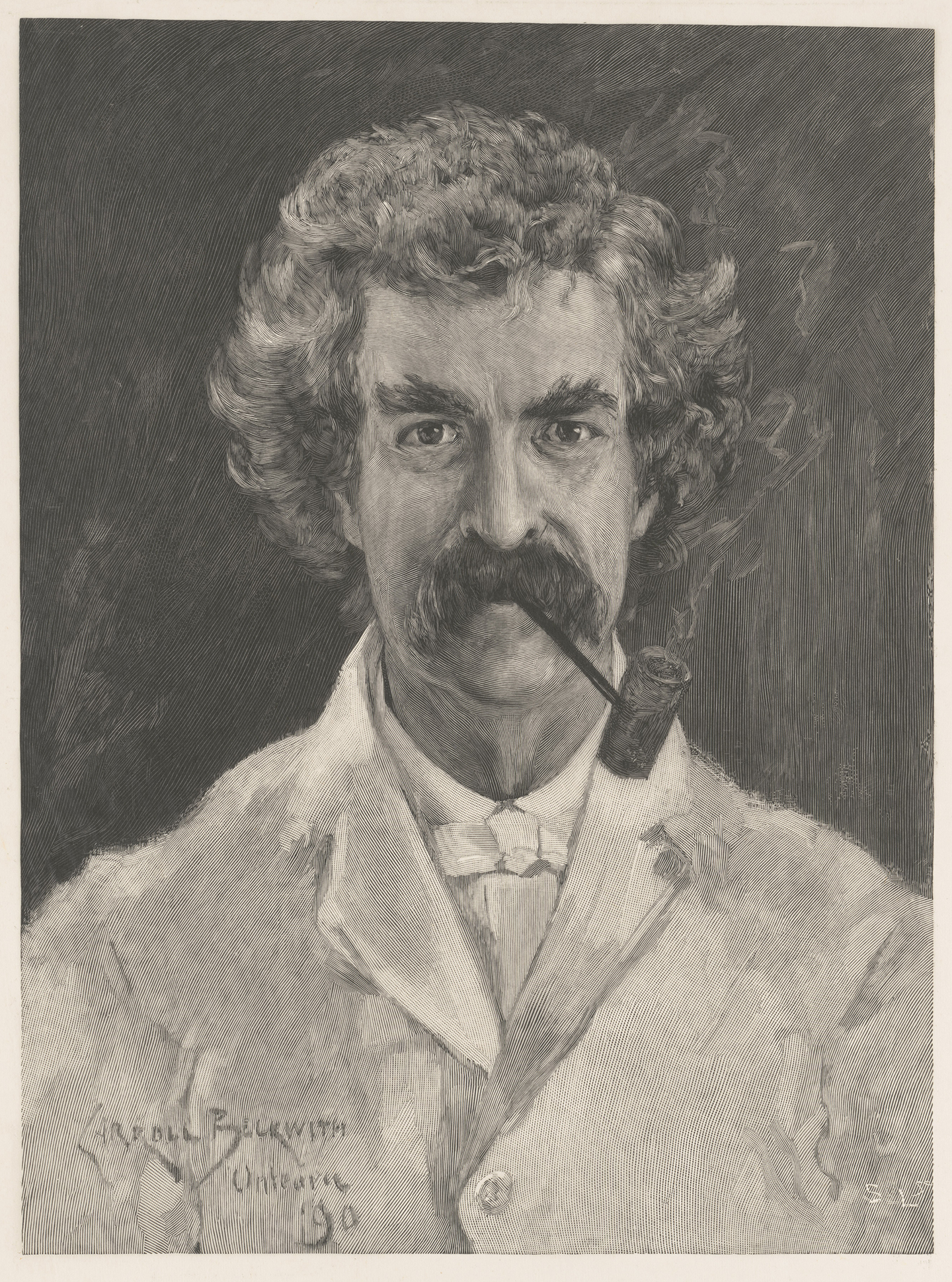

Mark Twain, born Samuel Clemens (1835–1910), was a man of many talents and many jobs. In his life, he worked as a riverboat pilot, silver prospector, newspaper reporter, adventurer, satirist, lecturer, and author of iconic American books. His years spent in this Hartford home were the happiest and most productive of his life, and he called it “the loveliest home that ever was.” While living here, he wrote his classic novels “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “The Prince and the Pauper,” and “A Connecticut in Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.”

Fit For a Literary King

Twain and his wife Olivia commissioned the New York architect Edward Tuckerman Potter, a specialist in ecclesiastical design and High Victorian Gothic style, to build their dream home. Twain was then primarily known for his travel writings and a novel that lampooned high society, yet the 25-room house announced intentionally his entrée into that very society. Measuring 11,500 square feet distributed over three floors, it epitomized a modern home of the time, with central heating, gas lighting fixtures, and hot and cold running water. As the building costs were substantial, with the couple spending between $40,000 and $45,000 on the construction, the interiors were initially kept simple.

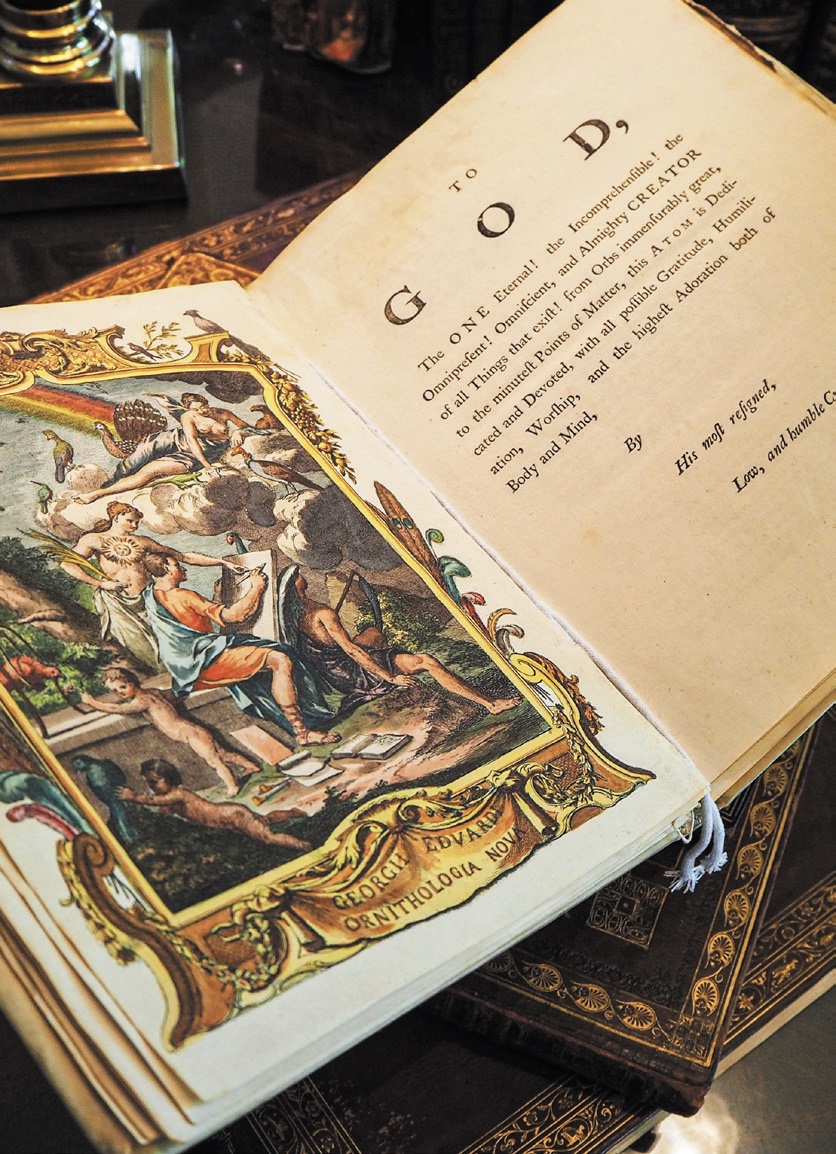

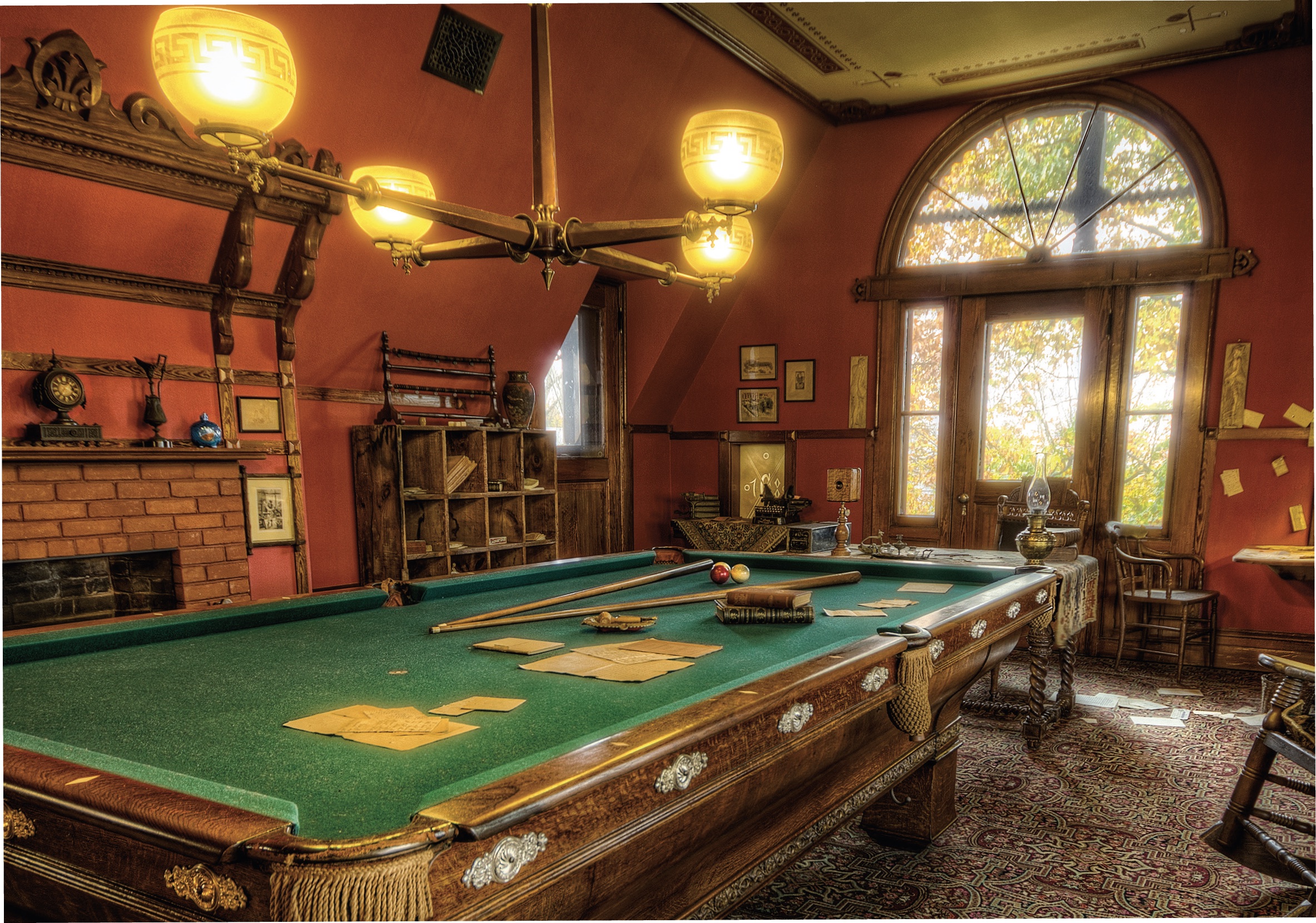

The house was used for delightful dinner parties, billiard games, charity events, and the raising of three daughters. In 1881, Twain’s growing international fame and success enabled the couple to renovate the home’s interiors in a grand and artistic manner. They engaged the fashionable design firm Louis C. Tiffany & Co.‚ Associated Artists, known for its globally inspired interiors.

Like Twain, Louis C. Tiffany was a creative genius and extensive world traveler, and he explored nearly every artistic and decorative medium. He was highly skilled in designing and overseeing his studios’ production of leaded-glass windows and lighting fixtures—for which he is best known today—as well as mosaics, pottery, enamels, jewelry, metalwork, painting, drawing, and interiors. In the same year that the firm embarked on the Twain house project, it was also hired to redecorate the state rooms of the White House. Interestingly, today, it is the Mark Twain House that is considered the most important existing and publicly accessible example of the design firm’s work.

The couple signed a $5,000 agreement giving Tiffany and his associate designers carte blanche in implementing a decorating scheme. The design work included the walls and ceilings for the newly expanded front hall, the library, the dining room, the drawing room, and the first-floor guest room, along with the second- and third-floor walls and ceilings visible from the front hall.

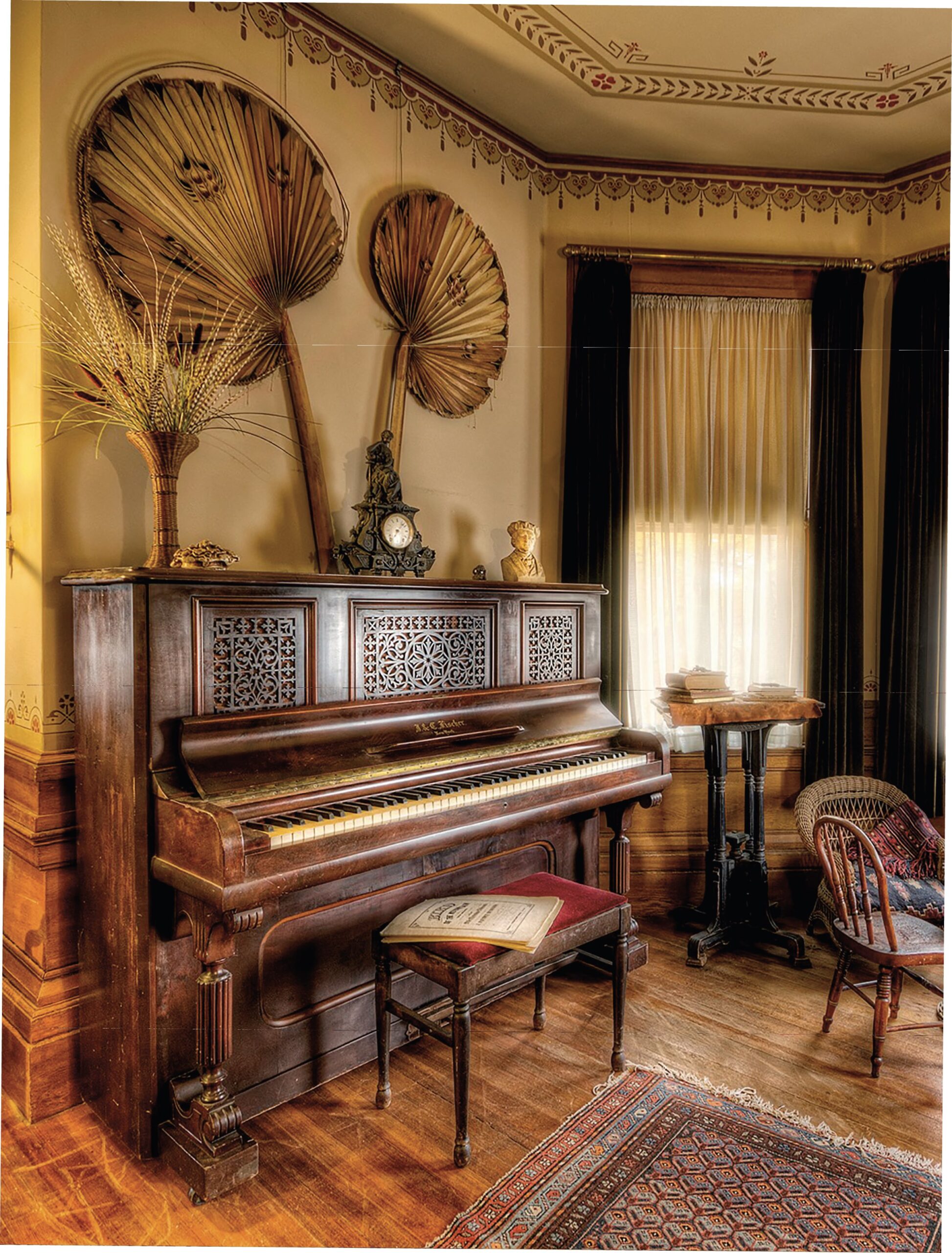

Louis C. Tiffany & Co.‚ Associated Artists’ cohesive decoration of the first-floor rooms is inspired by evocative motifs from Morocco‚ India‚ Japan‚ China, and Turkey. The entrance hall, carved with ornamental detail when the house was first built, had its wainscoting stenciled in silver with a starburst pattern and its walls and ceiling painted red with black and silver patterns. In the house’s gaslight, the silver paint would have flickered and given the exotic illusion of mother-of-pearl. The drawing room was given a base color of salmon pink, and Indian-inspired bells and paisley swirls were stenciled in silver. Today, one can still view a large pier glass mirror, a wedding gift to the Twains, as well as the family’s tufted furniture.

The dining room, used by the family for almost all of its meals whether informal or formal, was covered in a deep burgundy and gold-colored wallpaper in a pattern of Japanese style flowers. The paper’s pattern was embossed to give the impression of luxurious tooled leather. Its subject is typical of the work of Candace Wheeler, a partner in Associated Artists renowned for her textile and interior designs. Her honeycomb wallpaper enlivens the home’s best guest suite, known as the Mahogany Room.

Green and blue were frequent colors used in libraries at the time, and this house’s library is in a peacock blue. Its mantel, a large oak piece purchased from Scotland’s Ayton Castle, is the focal point of the room. Twain used the space to orate excerpts from his latest works, recite poetry, and tell stories to friends and family. In addition, Twain would entertain his daughters with fanciful tales using the decorative items on the mantelpiece as inspiration.

The family’s private rooms were beautifully decorated, too, and have been restored to their former glory by the museum. The nursery has delightful Walter Crane wallpaper that recounts the nursery rhyme “Ye Frog He Would A-Wooing Go” in words and pictures. Crane was an English artist considered to be one of the most influential children’s book illustrators of his generation; he created decorative arts in his distinctive detailed and colorful style.

The bedroom of Twain and his wife was dominated by a large bed with elaborately carved angels that they had purchased in Venice. Twain’s only surviving daughter donated the piece to the museum, where it continues to be displayed.

The third-floor billiard room is perhaps the most meaningful to fans of Twain’s writings, for it served as his writing office and study. When editing, he would lay out the pages of his manuscript on the billiard table.

A Change of Hands

Financial difficulties resulted in Twain and his family moving to Europe in 1891, and they never again lived in the home or even Hartford. They sold the property in 1903. Tiffany stained glass windows made for the home were sold separately, and their current whereabouts are unknown. The house went through different ownership and was, for a time, a school for boys before being sold to a developer who planned to demolish the house and turn it into an apartment building. A campaign was mounted to save the home, and, eventually, it was purchased by a group devoted to preserving its legacy.

The Mark Twain House & Museum, a National Historic Landmark, is considered one of the best historic house museums. Twain wrote in a letter that “our house was not unsentient matter—it had a heart, and a soul, and eyes to see us with. … We were in its confidence, and lived in its grace and in the peace of its benediction.” Fortunately, the home’s meticulous restoration and vibrant educational programming provides a window into its unique history and an opportunity to admire its timeless beauty.

Fun Facts

Mark Twain incorporated autobiographical events in his novels “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” The character of Finn, the beloved vagrant sidekick to Sawyer, was modeled off a boy he knew from childhood.

In his autobiography, Twain wrote, “In Huckleberry Finn I have drawn Tom Blankenship exactly as he was. He was ignorant, unwashed, insufficiently fed; but he had as good a heart as ever any boy had. His liberties were totally unrestricted. He was the only really independent person—boy or man—in the community, and by consequence he was tranquilly and continuously happy and envied by the rest of us.”

From March Issue, Volume IV