Though James Monroe is hardly the most memorable president, his foreign policy doctrine known as the Monroe Doctrine is without question the most lasting. Sean Mirski, in his new book “We May Dominate the World: Ambition, Anxiety, and the Rise of the American Colossus,” discusses just how the Monroe Doctrine was formulated, implemented, altered, and manipulated to transform the Western Hemisphere into a quasi-American protectorate.

The Monroe Doctrine may have been the foundation for America’s diplomatic and, at times, less than diplomatic foreign policy decisions, but as Mr. Mirski makes abundantly clear in his book, there were other foundational principles at play. The law of unintended consequences seems to be the bane of many of America’s diplomatic good intentions. These consequences were the result of America’s limited options, most of which were less than favorable. The author demonstrates how policies throughout various administrations, especially during the post-Civil War and early 20th century era, came to fruition out of sheer necessity. Those necessities arose out of fear and anxiety during a time of growing and fading empires, like the British, French, German, Spanish, and Japanese. Along with those Eastern Hemispheric empires, America found herself establishing her own in the Western Hemisphere by either conquest, happenstance, or the aforementioned necessity.

The Doctrine Tested

At the tail end of 1823, when Monroe addressed Congress in what would be coined the Monroe Doctrine, he advocated for remaining unentangled in European affairs (a reflection of George Washington’s 1796 farewell address), refraining from colonizing, and resisting the temptation to intervene in the affairs of other countries, unless of course the affair was an attempt by a European power to establish a foothold, by either governmental or corporate means, in the Western Hemisphere. These noble aspirations, as with all noble aspirations, are much easier to conceive than uphold.

As colonies throughout Latin America erupted with independence movements, revolving revolutions, and intrastate wars during the 19th and 20th centuries, this doctrine would be tested to the extremes, often resulting in unforeseen, or more appropriately, unintended consequences. In the book we are introduced to great and not-so-great diplomatic thinkers, like William Seward, James Blaine, Richard Olney, Elihu Root, Philander Knox, Robert Lansing, and Sumner Welles; varied foreign policies, like “masterly inactivity,” “reciprocity,” “Dollar Diplomacy,” “moral diplomacy,” and the “Good Neighbor Policy;” and geopolitical altering events like the annexation of Hawaii, the Spanish–American War, the Panama Canal, and World War I.

One of Mr. Mirski’s successes (among the many in his book) is his argument that America typically made its decisions based on national security interests, and not based on the notion of conquest and empire, or even economics. Indeed, it often came down to the aforementioned fear and anxiety that if America did not annex or intervene, one of the swarming imperial powers would.

A Problem at Every Turn

Readers of this review should not take this as Mr. Mirski writing an apologetic. “We May Dominate the World” is not revisionist history. Rather, it is a correction on much of the propagandistic history that has been issued over the decades by talking-heads rather than researching-brains. Mr. Mirski has, instead, taken the difficult route of demonstrating that foreign policy is a difficult science―far more difficult than we credit it.

While many historians and political scientists choose a singular politician and his or her foreign policy, say a Theodore Roosevelt or a Woodrow Wilson, or a particular motivation, like racism, colonialism, culture, or economics, Mr. Mirski shows that American foreign policy has always been a multi-faceted arrangement of motivating factors, decisions, actions, regrets, and the continued cycle of such an arrangement. The author’s work proves that no matter how powerful a nation is, it cannot control the world; it can only try and fail.

Those failures ironically stemmed from attempts to stabilize newly independent countries or nations laden with incessant and violent revolutions. Unfortunately, these attempts often “created perverse incentives” for further revolutions in order to initiate American military intervention (such as the Platt Amendment with Cuba).

The Logical Result

The failure of American diplomacy in the region seemed to hit a fever pitch deep into the Wilson administration. As Mr. Mirski notes, “By the end of the Wilson administration, the United States had boxed itself into the ultimate catch-22: any leader who cooperated with the United States, lost the domestic legitimacy needed to govern, but without the United States’ support, no leader could hold onto power. In the most extreme cases, the logical result was direct American rule.”

The logic behind America’s growing power seemed evident to Roosevelt well before Wilson’s term in office, when he stated during his 1904 State of the Union address that the Monroe Doctrine, if strictly adhered to, would force America into an “international police power.” By the middle of the 20th century, America had taken all of its experience―successful and otherwise―and expanded the regional doctrine internationally.

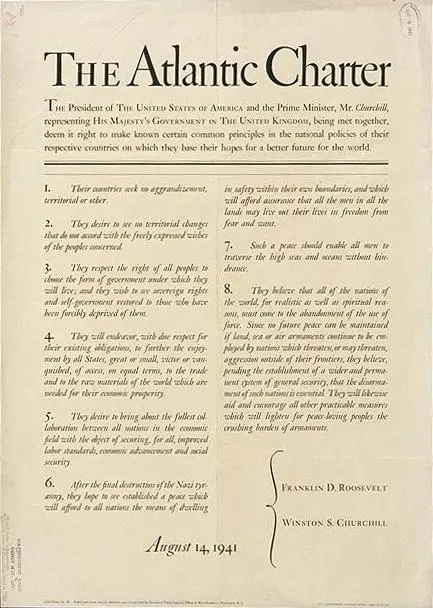

“After the war the United States scaled up its regional policies and institutions to create the new international order,” Mr. Mirski writes. “It is no coincidence that the Atlantic Charter―FDR and Winston Churchill’s celebrated blueprint for the postwar world―was drafted in large part by Welles, the State Department’s preeminent Latin American expert. Welles also drafted the United Nations Charter, a document that reflects Welles’s Latin American experience through and through.”

Mind Your Own Business

This book proves the difficulty of minding your own business, especially when it appears that doing so will only make matters worse. But as the author points out, more often than not, America did try to mind its own business.

“Officials in Washington had no premeditated plan to reduce the whole region to vassal status,” Mr. Mirski states. “As impressive as the number of American interventions is, the more revealing figure is the far greater number of times that Washington declined its neighbors’ invitations to send troops, annex territory, or establish protectorates. For all its interventionism, Washington proved remarkably reluctant to take advantage of opportunities to extend its regional control.”

This statement will no doubt be the ire of some who believe that there was always a plan for domination and to keep the weaker Latin nations under America’s thumb. Cynicism has long been the order of the day, and any statement, much less a book, contrary to that belief cannot possibly be true. But if truth is actually the pursuit, then Mr. Mirski’s work should be at the very top of the reading list for foreign policy hawks, history buffs, and young people going to college. No doubt the latter will encounter the onslaught of academics who profess to have the market cornered on American foreign policy—but are typically mere subscribers to the aforementioned propagandistic history.

Don’t Oversimplify

Mr. Mirski speaks to this issue of oversimplifying the history of foreign policy. “Observers often see international politics as a clash between good and evil. Sometimes it is,” he writes. “But more often than not, international politics takes place in a gray world under gray skies, where every decision requires trade-offs and difficult choices, where legitimate ends pursued rationally still lead to unsavory destinations, and where tragedy is all but inescapable. Tales pitting good against evil appeal to the human desire for moral certainty, but they are often poor vehicles for understanding the choices nations face.”

“We May Dominate the World” thoroughly demonstrates just how gray that world is and just how inescapable the consequences of good intentions are. As the author notes, this is “the tragedy of great-power politics.”

Mr. Mirski has proven himself to be a researcher and a writer of exceptional talent. My expectations for his future works are now practically limitless. “We May Dominate the World” is an absorbing read and is quite possibly my favorite selection of 2023.

‘We May Dominate the World: Ambition, Anxiety, and the Rise of the American Colossus’

By Sean A. Mirski

PublicAffairs, June 27, 2023

Hardcover: 512 pages

Sean A. Mirski is a lawyer and U.S. foreign policy scholar who has written extensively on American history, international relations, law, and politics. He graduated from Harvard Law School and holds a master’s degree in international relations from the University of Chicago.

From March Issue, Volume IV