“The hills bear all manner of fantastic shapes,” Charles Bessey observed, noting that they sometimes featured open pockets of bare sand in blowouts and were “provokingly steep and high.” Bessey was describing the Sandhills, the area of post-glacial dunes wrought by mighty winds in north-central and northwestern Nebraska. Aided by his botany students from the University of Nebraska (today’s University of Nebraska–Lincoln), he cataloged a treasure of plant species in 1892. Yet besides spurges and gooseberries, herbaceous plants such as smooth beardtongue, and grasses such as Eatonia obtusata, he found the potential for forestation.

“He was convinced that the moist soil of the Sandhills would support forest growth,” the historian Thomas R. Walsh wrote. Nebraska had gained statehood in 1867 but still had enough untouched areas to be “a virgin natural laboratory,” as Walsh described it. And there were so few trees for wood, shelter, or shade. Bessey had been pushing the state legislature to reserve Sandhills tracts for tree planting. In 1891, urged by the top forestry official in Washington, D.C., he started a test plot at the eastern edge of the Sandhills, which encompassed an area about the size of New Jersey. Ponderosa pines were a big component of the experiment’s 13,500 conifers. With the initial indication that they would do fine, he started a campaign to convince people that forestation was practical. After all, as Walsh noted, “the area was once covered by a pine forest that was destroyed by prairie fires.”

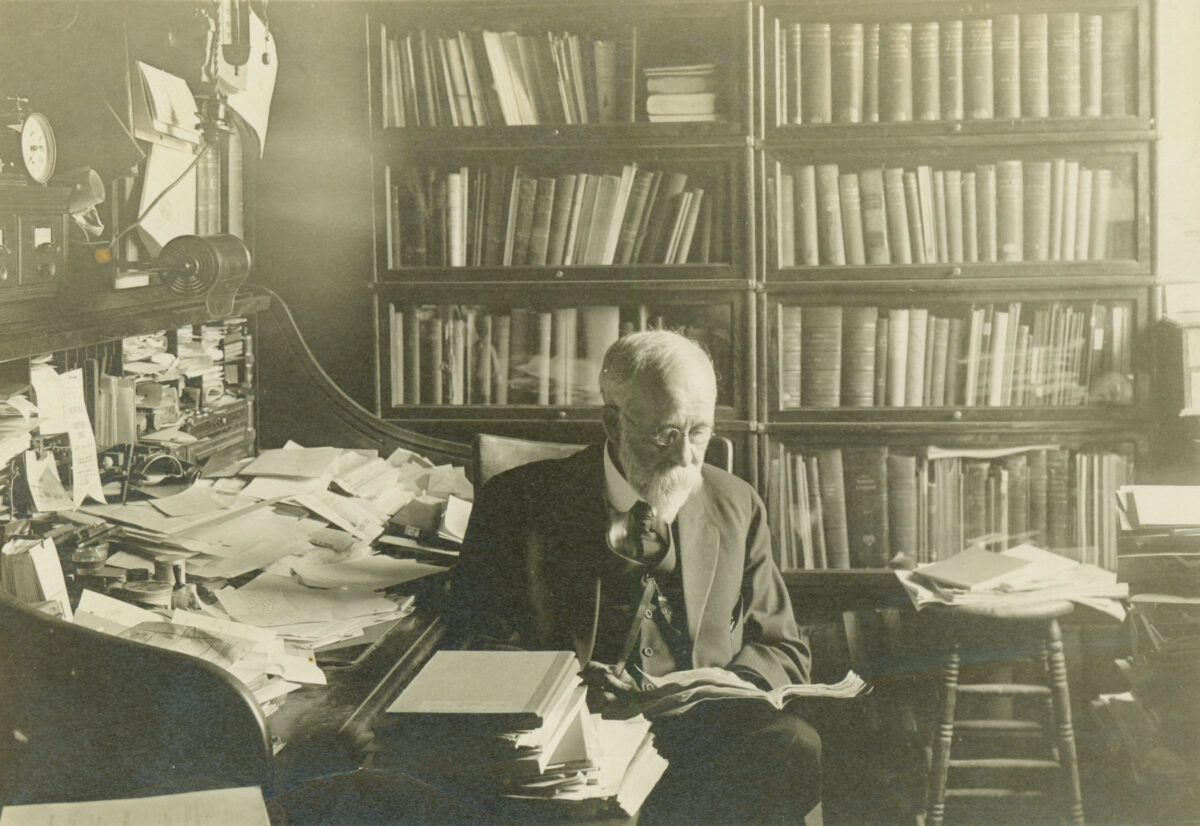

Bessey had come to the University of Nebraska in 1884, lured from Iowa Agricultural College (today, Iowa State University) by an offer of $2,500 per year. He was already the author of “Botany for High Schools and Colleges,” the nation’s first textbook on the subject. His motto of “Science with Practice” indicated a teaching philosophy that mixed laboratory and field work with classroom instruction. He was one of a small group of professors at the prairie university, attended by just 373 students in the year he arrived, but he had an outsized and enduring influence through his popular botany seminar. A top student in the 1892 cataloging project was Roscoe Pound, who claimed the university’s first Ph.D. in botany, then distinguished himself as a legal scholar and served two decades as dean of Harvard University’s law school.

Throughout the latter years of the Gilded Age, Bessey kept hammering away at the idea of national forests. To Gifford Pinchot, head of the national Division of Forestry, he wrote, “In the Sandhills, we have a region which has been shown to be adapted to the growth of coniferous forest trees, and here we can now secure large tracts which are not yet owned by private parties.” Pinchot had the ear of President Theodore Roosevelt, who in 1902 set aside 206,028 acres in two reserves in the Sandhills. “This was the first and only instance in which the federal government removed non-forested public domain from settlement to create a man-made forest reserve,” Walsh explained.

The two reserves are 75 miles apart. The northern Samuel R. McKelvie National Forest is on the Niobrara River near the city of Valentine. The southern one, first called Dismal River Forest Reserve, is now the Nebraska National Forest at Halsey and is managed by the Bessey Ranger District. (Nebraskans refer to it as “Halsey Forest.”) Within it are the Bessey Recreation Area and the crucially important Charles E. Bessey Tree Nursery, which yearly produces 1.5 million bare-root seedlings and up to 850,000 container seedlings for distribution in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states. Additionally, the nursery acts as the seed bank for Rocky Mountain Region 2, storing about 14,000 pounds of conifer seeds in case of wildfire or insect infestation.

Carson Vaughan, author of “Zoo Nebraska: The Dismantling of an American Dream,” grew up in Broken Bow, about 50 miles from Halsey Forest. It was only after he started writing articles about Bessey and the forest that he comprehended the magnitude of the original undertaking: creating the largest man-made forest in the United States. “Nothing like this has ever happened anywhere else on the planet,” he said. “And it all started because this pioneering botanist, Charles Bessey, had this wild idea and the patience, the dogged persistence, to stick with it over a couple decades and see it come to fruition.”

Vaughan remembered climbing Scott Lookout Tower, near Halsey, and feeling the impact upon viewing a forest amid treeless grasslands. “You get the rolling, billowing Sandhills right next to this very clear, dark, dense forest,” he said. The experience reinforced the concept that “it took human beings planting all of these trees to make this national forest grow out of this sandy, arid region.”

After succeeding in the Sandhills, Bessey turned to other important challenges. In 1903, he was contacted about the effort to save the giant sequoias in certain groves in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. He tried to interest President Roosevelt in the cause, then introduced the matter into proceedings of scientific societies, sending their resolutions on the matter to congressional representatives. Although he helped to set the conservation process in motion, Bessey would pass away in 1915 without seeing his efforts bear fruit. 16 years later, the state of California acquired the Mammoth Tree Grove, which is a principal element of the eventual Calaveras Big Trees State Park.

On the other side of the country, Bessey became involved in the effort to create a national forest reserve in the southern Appalachians. “The cutting away and total destruction of the forests is a crime against the community as a whole,” he wrote. In 1908, a bill to authorize the reserves came before the House of Representatives, but soon died. It particularly galled Bessey that one of his former students, Representative Ernest M. Pollard, was on the agricultural committee, which had deferred action. “It does seem as though we had the most stupid and blinded lot of men in charge of our affairs that has ever cursed any country,” Bessey wrote to House Speaker Joseph G. Cannon. Bessey and others kept working, and ultimately, the Weeks Act of 1911 was passed, providing for acquisition and preservation of forested lands nationwide.

Today, visitors to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln can see an image of Bessey in bas-relief on a bronze tablet at—where else?—Bessey Hall. There’s also a Bessey Hall at Iowa State. And at Michigan State University, Ernst Bessey Hall is named for Charles’s son, who became a professor of botany and dean at MSU’s graduate school from 1930 to 1944. The apple didn’t fall far from the tree.