It was December 1777, one of the bleakest times during the Revolutionary War. The Continental Army had won a few battles; however, morale suffered as they had also lost a few crucial battles, such as the Battle of Long Island, the Battle for New York, the Battle of White Plains, and the Battle of Bennington. As it was common for armies to take up quarters during the winter, General George Washington chose his army’s quarters to be constructed 25 miles north of Philadelphia, near Valley Forge. The location was strategic—the British Army had captured Philadelphia that fall and the land area had small creeks that would impede attacks due to its uphill location.

The prospects looked dire for the 12,000 men encamped at Valley Forge. The roads were impassable due to snow. The Continental Army was undersupplied and underfed. The men were neglected, with tattered clothing, worn-out shoes, and disheveled hair. Their constructed shelters were dark, cold log huts with dirt floors, a pit, and a sheet for the door, and there were 12 men per hut, leading to rampant disease.

Historians estimate somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 men died in that bitter cold winter. In Philadelphia, the Red Coats were well taken care of, quartering themselves in American homes and availing themselves of their supplies while guarding the city to prevent supplies from being directed to the Valley Forge camp.

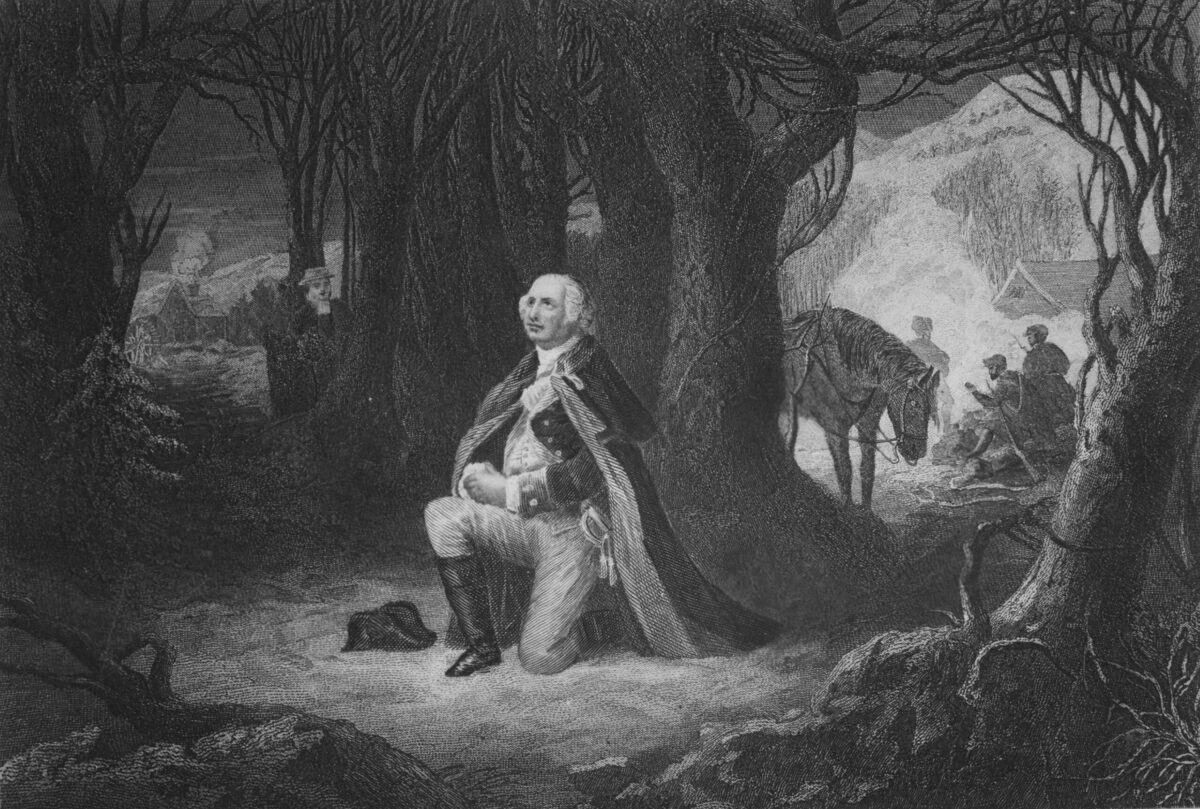

As the story is told by Reverend Snowden in his “Diary and Remembrances,” Isaac Potts, a Quaker, a Tory, and a pacifist, was strolling through the woods in Valley Forge during the winter.

“I heard a plaintive sound as, of a man at prayer,” Potts said. “I tied my horse to a sapling and went quietly into the woods and to my astonishment I saw the great George Washington on his knees alone, with his sword on one side and his cocked hat on the other. He was at Prayer to the God of the Armies, beseeching to interpose with his Divine aid, as it was His crisis, and the cause of the country, of humanity, and of the world. Such a prayer I never heard from the lips of man. I left him alone praying. I went home and told my wife, ‘I saw a sight and heard today what I never saw or heard before,’ and just related to her what I had seen and heard and observed. We never thought a man could be a soldier and a Christian, but if there is one in the world, it is Washington. She also was astonished. We thought it was the cause of God, and America could prevail.”

A Pivotal Moment

Not only was this a pivotal moment for Isaac Potts—he switched to the Whig party and was now a supporter of the war—it also appeared to be a pivotal moment for the Continental Army. Baron von Steuben took command; utilizing his manual “Regulation for the Order of Discipline of the Troops of the United States.” He created a schedule, conducted drills, and instructed on the use of bayonets and battlefield formations and maneuvers. The spring of 1778 brought the French to the side of the Americans. France and America replenished food and supplies and built new roads and bridges. In June 1778, the British abandoned Philadelphia and retreated to New York. At the end of that same month, the British withdrew at the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey. As more dominoes fell, eventually the British surrendered in Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781.

The prayer of Washington is seen by many as the pivotal moment that changed the trajectory of the Revolutionary War. This one pivotal moment is depicted in various works of art, including Arnold Friberg’s painting, “The Prayer at Valley Forge.” George Washington was a deeply religious man. He held a deep and abiding faith that God had put him in his position and that victory would come for the Americans. He encouraged days of prayer and fasting to seek God’s divine assistance in times of peril. Washington’s belief in freedom of religion and conscience was exemplified in his support of the Bill of Rights, his respect for the conscientious scruples of the Quakers, and his assurance to the Hebrew Congregations of Newport, Rhode Island, that they would be able to enjoy “the exercise of their inherent natural rights” and that the government would protect their religious freedoms.

This country has had other archetypal leaders who answered their calling and displayed their devotion to God and the higher law principles that it was founded upon. And their prayers seem to have been answered, as time and again the trajectory of this nation has changed. Think of Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., and John F. Kennedy. These leaders emerged with spoken and written words humbly acknowledging that our rights come from God, not the state, and that there are self-evident, objective truths. Their leadership changed the trajectory of this country, adversity was overcome, and this nation eventually healed.

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan, another iconic leader, stated: “I said before that the most sublime picture in American history is of George Washington on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge. That image personifies a people who know that it’s not enough to depend on our own courage and goodness. We must also seek help from God our father and preserver.” Reagan had Arnold Friberg’s painting on display in the White House all eight years of his presidency.

Historically as a nation, during disunity, Americans have grasped the gravity of the moment and, like their preceding iconic leaders and contemporary Americans, have returned to God and the founding principles that were embedded in the founding documents. Over the past year, it appears as though the earth has once again shifted. Not unexpectedly, Bible sales are soaring and there is an increased interest in understanding our country’s heritage. The American spirit is yet again awakening and renewing its religious and cultural allegiances.

Deborah Hommer is a history and philosophy enthusiast who gravitates toward natural law and natural rights. She founded the nonprofit ConstitutionalReflections (website under construction) with the purpose of educating others in the rich history of Western Civilization.