In 1962, our young, charismatic president John F. Kennedy was entertaining the year’s Nobel Prize winners at the White House. He said of the group, “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.” It is a great statement, to be sure.

Feasts of Wisdom

The journals of Margaret Bayard Smith tell us some interesting details about her visits to the “President’s House,” where she and her husband actually dined with Thomas Jefferson, our country’s third president. Margaret Smith came to Washington as a young bride in 1800. Her husband was a newspaperman and a strong supporter of Jefferson’s bid for the presidency. The Smiths and Jefferson frequently entertained each other. Unfortunately, Jefferson’s wife, Martha, had died years earlier in 1782.

The President’s House, far from being the stately edifice we know today, was a work in progress. Jefferson’s personal quarters were furnished as befit a man of his many interests. Smith writes; “The apartment in which he took most interest was his cabinet; this he had arranged according to his own taste and convenience. It was a spacious room. In the centre was a long table, with drawers on each side, in which were deposited not only articles appropriate to the place, but a set of carpenter’s tools in one and small garden implements in another from the use of which he derived much amusement. Around the walls were maps, globes, charts, books, etc.” This collection is reminiscent of Jefferson’s personal effects at Monticello. He placed such importance on reading that he would often greet his guests while putting down a book, both at the President’s House and back home in Monticello.

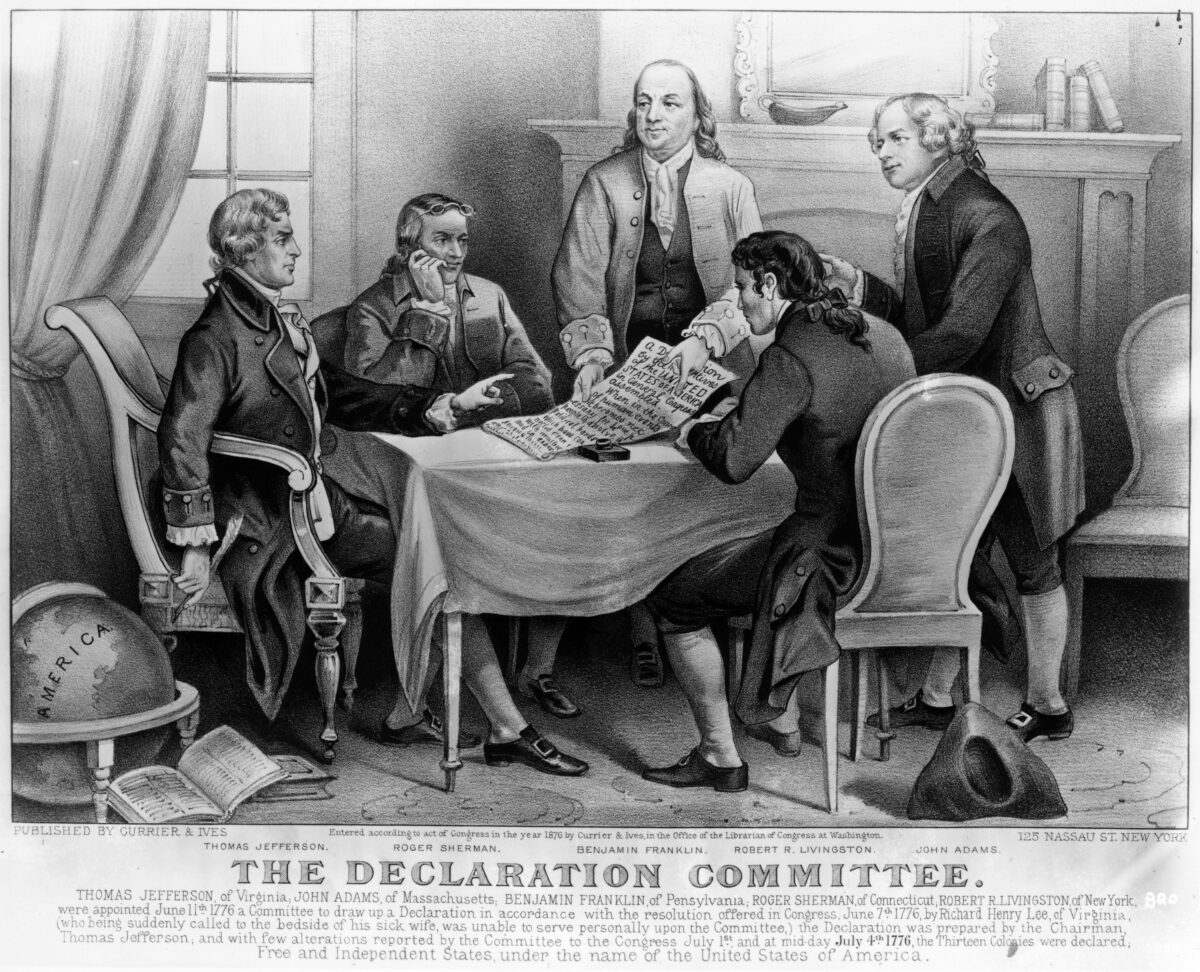

Jefferson had no long, rectangular tables where guests would sit in long rows, awkwardly conversing with those assigned within earshot. Instead, Jefferson introduced a round table and limited the number of guests to around 14. He preferred to be addressed as “Mr. Jefferson,” not “Mr. President.” The man truly enjoyed lively discussion, and this arrangement assured that no one was left out of it.

Far from reveling in his own words, Jefferson surrounded himself with a rich feast of wisdom, made all the more enjoyable by the implementation of intimacy and courtesy. His guests tended to be interesting people such as Alexander von Humbolt, the great Prussian naturalist and baron. Jefferson loved to mix such intellectuals with the important people of government whom he might have felt compelled to entertain. Smith certainly gives the impression that these were rich events to be savored rather than social obligations to be endured. She notes:

“Guests were generally selected in reference to their tastes, habits and suitability in all respects, which attention had a wonderful effect in making his parties more agreeable, than dinner parties usually are; this limited number prevented the company’s forming little knots and carrying on in undertones separate conversations, a custom so common and almost unavoidable in a large party. At Mr. Jefferson’s table the conversation was general; every guest was entertained and interested in whatever topic was discussed.”

Smith describes the fare as a mixture of “republican simplicity … united to Epicurean delicacy.” His guests loved it. Southern staples such as black-eyed peas and turnip greens shared the stage with delicacies prepared by Honoré Julien, the president’s French chef. We know that Jefferson loved and served fine wine, as well as macaroni and cheese created from his own recipe.

Lively Affairs

Jefferson was a man who never stopped learning, and these dinners were certainly an extension of that fact. His favorite parties were those limited to four. To keep the conversation flowing, Mr. Jefferson brought his inventiveness to the room’s design: He installed dumbwaiters and placed revolving shelves in the walls so that the distraction of serving dishes and clearing the table, typically accompanied by servants and the opening and closing of doors, was minimized.

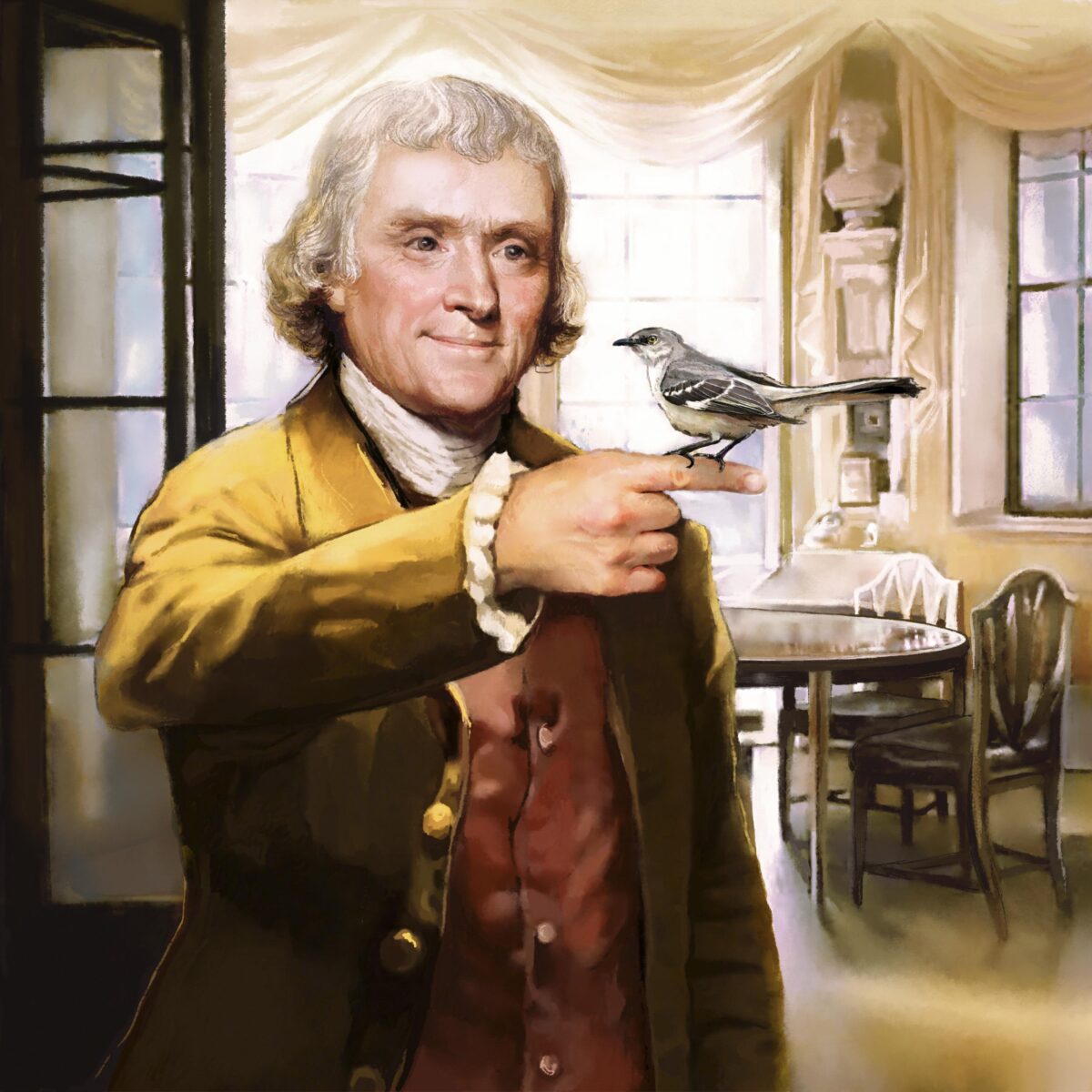

That’s not to say there were no distractions, however. There was Jefferson’s pet bird, which “would alight on his table and regale him with its sweetest notes, or perch on his shoulder and take its food from his lips. … How he loved this bird!”

After dinner, guests might stretch their legs with a visit to the house gardens. Since Congress refused to appropriate money for improving the grounds, Jefferson did so at his own expense. It, too, was a work in progress. Jefferson, who planted European grapes at Monticello, did not do so at the President’s House. He chose instead to display flora and fauna native to America. For several months, guests could see two live grizzly bear cubs that Captain Zebulon Pike had acquired during his expedition along the Arkansas River.

Egalitarian dining, surrounded by the wonders that Jefferson collected, inevitably led to a convivial discussion. Here, ideas that shaped the course of a young nation would find lively expression.

From January Issue, Volume 3