Our house has brought together two people—my husband and myself—along with 17th-, 18th-, and early 19th-century hand-water-colored prints of flora and fauna from around the world, which decorate our walls today. They speak of the glory of God’s creation.

Gilbert and I met in Washington, D.C., during the Ronald Reagan administration. He was working on Capitol Hill as a legal aide to a friend elected to Congress, then later to an Alabama senator. I was working as deputy social secretary to the White House, where I would eventually become the social secretary during the final three-and-a-half years of Reagan’s administration.

Gilbert’s milieu, Capitol Hill, or “The Hill,” as it is called, will always hold a fascination for me because I never worked within those hallowed halls. What I knew was the White House. As Social Secretary, I was responsible for producing all events hosted by President Ronald Reagan and first lady Nancy Reagan—usually in the White House, but one was in New York, and one at the American embassy in Moscow. One fun memory was during a 1985 White House dinner to host Prince Charles and Princess Diana: I tapped John Travolta on the shoulder to ask him to cut in on the President and dance with the princess. An iconic photo ensued.

Working in the White House

I greatly enjoyed working with Mrs. Reagan. She was the consummate hostess and a gift to our country. What fun we had deciding not only who would be invited to sumptuous state dinners, but who would sit next to whom. One of my favorite duties was advising Mrs. Reagan about entertainers at the White House, from the brilliant pianist Van Cliburn, who performed at a state dinner in honor of then-Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife, to the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, which performed at a Congressional picnic in 1986.

After the administration, Gilbert and I lost touch, he returning to Alabama and I to Texas. But years later, we eventually, and thankfully, reconnected—neither of us having married. When he began to talk about marriage, Gilbert secretly planned a destination event six months thence, at which he was planning to pop the question. He asked me, pre-proposal, where I would most like to live someday (he was still in Birmingham but liked smaller towns, and I was in Dallas), and the words “Terrell” flew out of my mouth.

Annandale: Home Sweet Home

Terrell, Texas, is within commuting distance to Dallas, where I am vice president of communications and public relations for The Tradition, which develops and manages luxury rental retirement communities in Texas. I knew that this small town had a beautiful historic district with homes originally built with wealth from the cotton and cattle industries. The first automobile to be purchased in Texas was by a resident of Terrell.

Gilbert went online and found this exquisite Georgian revival home with a carriage entrance for sale in Terrell. The home had, however, a potential buyer on the brink of commitment. So, he quickly proposed over the telephone (who wanted to wait six months for a proposal, anyway?)—and we bought the house!

Our house was built in 1917. It was historically a focus of entertainment, with its annual “silver charity teas”—where people would bring silver coins to donate to charity—and its third-floor ballroom, which hosted dances for Terrell young ladies and British cadets from the No. 1 British Flying Training School during World War II. The famous Texan and 20th-century speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Sam Rayburn had been a guest here.

We call our stately home “Annandale,” for the Scottish location of Gilbert’s ancestors (who are related to Samuel Johnston, an 18th-century statesman who was a delegate to the U.S. Continental Congress). We love history and have honored it by highlighting the work of scientific artists who lived during the golden age of natural history and exploration. It was a time when educated, cultured Europeans and Americans—undergirded by the findings of early scientists such as Johannes Kepler, Isaac Newton, and John Ray—became consumed by the desire to discern the world around them. They were driven by a missionary zeal to understand God’s creation as completely as they could and spread that knowledge to others. They felt compelled to read “the unwritten book of nature,” i.e. the created world. The written Bible and the “book of nature,” a term used by Saint Augustine and early Christian theologians, were understood as the two ways to learn about the Creator.

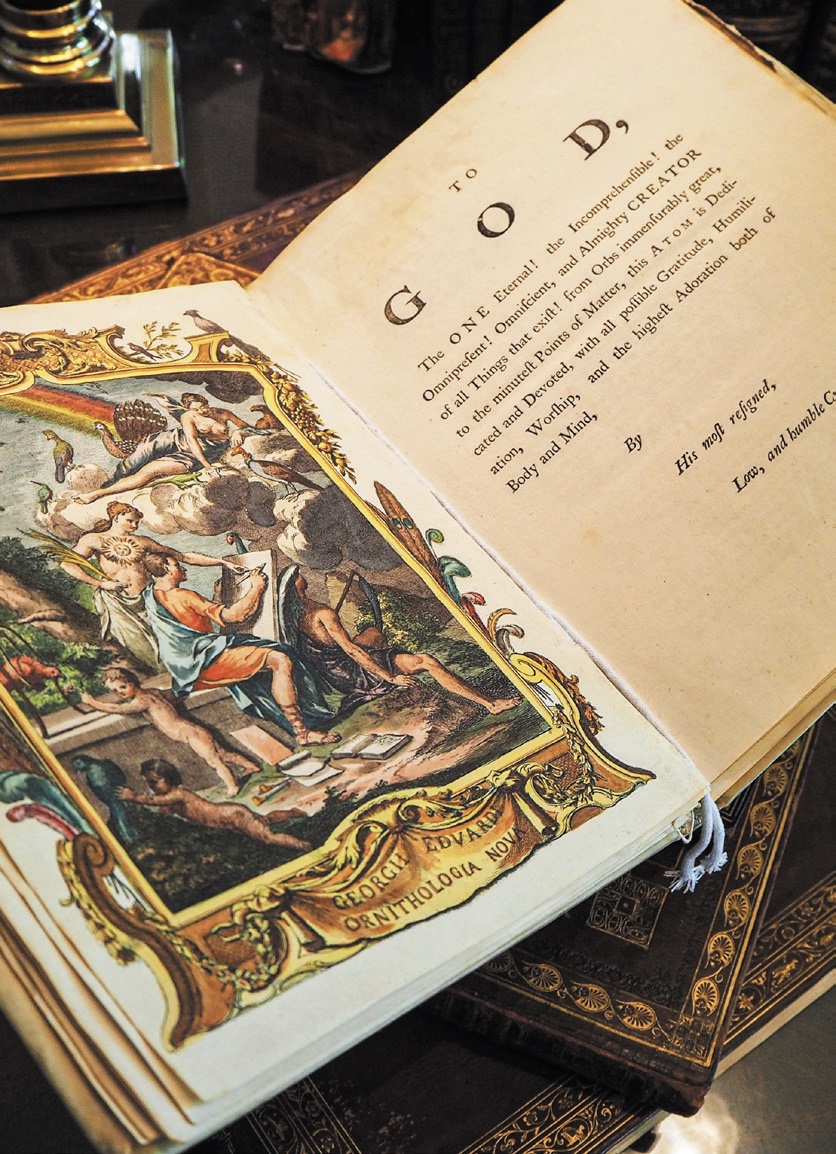

These natural history scientists and artists enjoyed a lifelong appreciation for God’s creation, which generated wonder, praise, and joy. As the great musical composers Bach and Handel dedicated their talents to God’s glory (soli Deo gloria), so did these men and women. In notable entomologist Maria Merian’s (1647–1717) first book on caterpillars and butterflies, she made beautiful drawings of plants and insects. She wrote: “Seek not in this to honor me but God alone, to praise him as the Creator of even the smallest and least of worms.” Beautiful, hand-painted prints by these artists were ultimately gathered in leather-bound books. In addition to Maria Merian, others such as Basilius Besler (1561–1629), Mark Catesby (1683–1749), George Edwards (1694–1773), Moses Harris (1730–1788), John James Audubon (1785–1851), and Sir William Jardine (1800–1874) are just a few of these important natural history artists and scientists.

The scientific art now hanging on our walls is set among the beauties of natural objects—minerals, shells, and butterflies—as well as among period English, American, and French furniture, some of which was passed down through our families. The art, furniture, and architecture recreate a Georgian period interior on a smaller scale, not unlike homes of earlier centuries that exhibited this “passion for natural history.” These iconic houses were filled with cabinets of curiosities—collections of striking birds, insects, minerals, and more—along with libraries stocked with exquisitely tooled, leather-bound, natural history color-plate books. The grounds and spectacular gardens of their homes were planted with the most recent botanical discoveries of the day.

Gilbert has nurtured a love of nature throughout his life, and he has witnessed great nature sites on six continents. He has backpacked, canoed, and kayaked throughout North America.

He subsequently transformed our lot into a nature-friendly haven by planting flowers and shrubs that provide food for butterflies and birds, with many bird baths and feeders. We look forward to seasonal changes because of the different migratory birds that visit our yard. Gilbert has identified over 100 different bird species here over the years. And I can now identify a downy woodpecker!

The Interiors

Today, almost eight years after our wedding, I walk through the rooms of our house and am grateful for our life together. When I was working in the White House, I was constantly surrounded by the beauty of Federal-style decor, very similar to its Georgian counterpart in England. And now, the beauty of the same period surrounds me. Natural light pours in from Palladian windows, filling the ground-floor rooms and illuminating our art.

Nothing is fully appreciated unless it is understood, and for that purpose, Gilbert has placed “museum-like” cards alongside each work of art in our home, explaining something about the artist and how the work was produced. We regularly open our house to others to share beauty and historical information.

However, do not let the word “museum” deceive—our home is anything but. Vibrantly colored walls, true to Georgian decor, warm up the rooms with rich yellow, apricot, and blue hues—which leads me to a word about the decorator. Having known my husband since the 1980s as a master of conservative public policy, an adventurer in the wilds, an art collector, a print dealer and owner of Antique Nature Prints, and a lecturer on the art of natural history (my Renaissance man), I had never known him as an interior decorator! And yet, he set about decorating our home with a sure hand—just as he landscaped our land—suggesting paint colors, purchasing furnishings at auction, and placing the art and furniture so happily together that they seemed made for each other.

Which is just what I feel about us—made for each other. And any beauty in our home is dedicated to the glory of the Author of beauty—the Lord of Creation.

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.