These days, place settings at your dinner table might look like this: a knife, fork, spoon—and cell phone. You might watch television as you eat.

You’re missing the key to a good meal, says renowned chef Geoffrey Zakarian: family.

Mr. Zakarian learned this lesson at a young age. He grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts, with a Polish American mother and Armenian American father.

“Being Middle Eastern, all we did was cook,” he said. “At breakfast, we’re talking about lunch with our mouths full. At lunch, we’re talking about dinner with our mouths full. It was a never-ending circle.”

Mr. Zakarian saw that a meal was about more than just good food. It was the glue that bonded his family.

“It created a shared devotion around the table,” he said. His love of food and its effect on family eventually led to his calling as a chef.

Fighting Hunger in the City

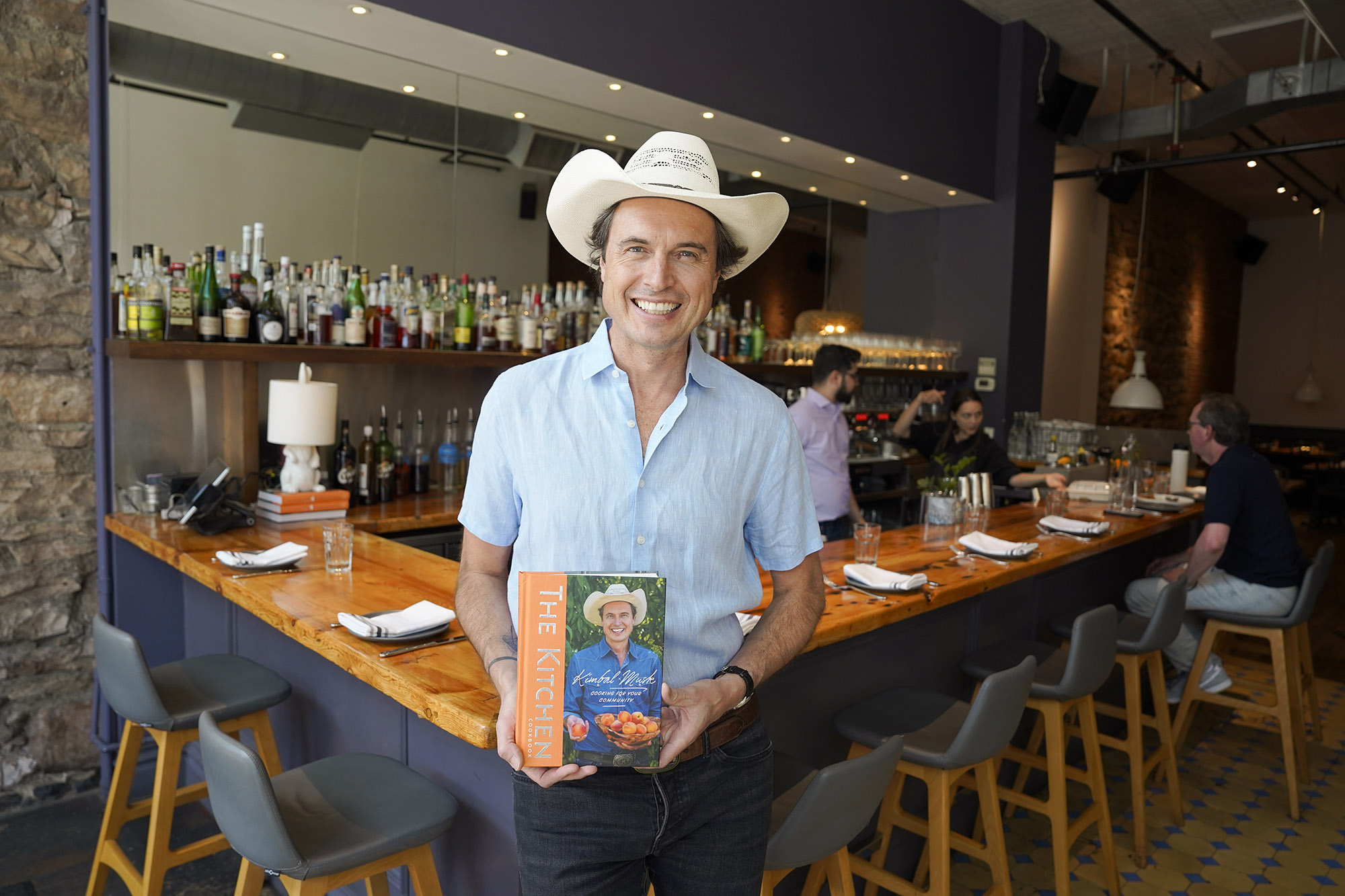

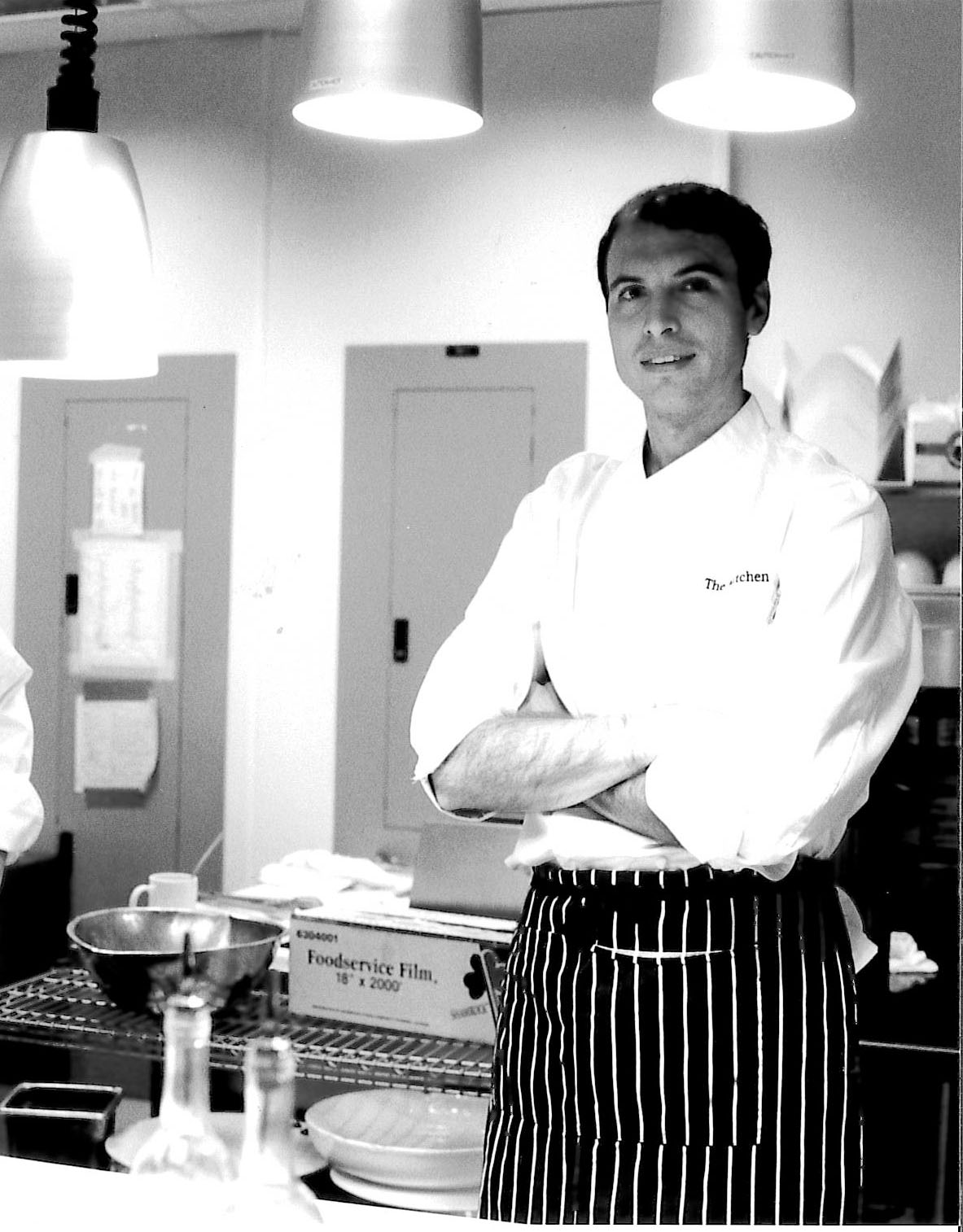

Mr. Zakarian is not only a prolific chef and restaurateur—whose ventures have included restaurants in New York, Connecticut, Los Angeles, and Florida, where he now lives—but also a long-standing television personality, known for his appearances on the Food Network as an Iron Chef, a recurring judge on “Chopped,” and a co-host on “The Kitchen.”

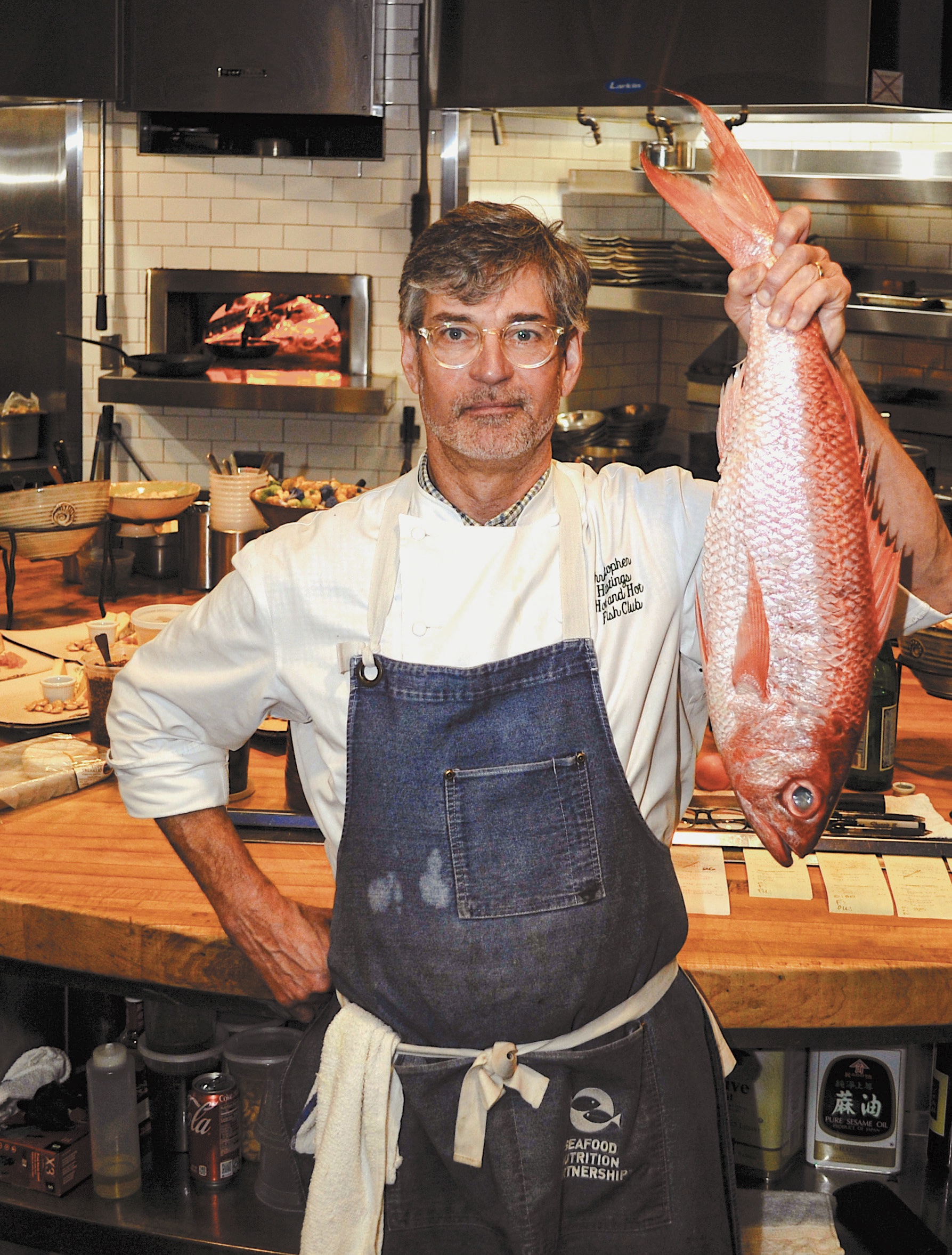

He’s also worked for years with City Harvest, a New York food rescue organization that has distributed an incredible 80 million pounds of food this year to New Yorkers in need. He’s served as chairman of the NGO’s Food Council since 2014.

City Harvest rescues much of its food because of something that might surprise you: expiration dates. “This would not be possible unless a terrible legislation for expiration dates was created. That created a false foundation where we have to throw food out [after its sell-by date] and can’t sell it,” Mr. Zakarian said. “City Harvest came along and said, ‘We’ll take it, and, in less than 24 hours, we can distribute it.’”

When asked how much of the “expired” food the charity gets is still edible, the chef has a stunning answer: “One hundred percent.”

City Harvest receives donations of surplus food from nearly 2,000 businesses, including farms, grocers, restaurants, wholesalers, and manufacturers. But Mr. Zakarian makes sure to distribute healthy food, shopping as carefully as he would for his own family.

“Nothing with high fructose corn syrup. We’re very picky [about] what we take. Fifty percent of what we give away are fresh vegetables,” he said.

City Harvest trucks then deliver the food free of charge to more than 400 food pantries, soup kitchens, and other community food programs across the city. “It’s a very fulfilling process for everyone,” he said. “If you talk to any of the drivers, they’re so happy with what they do. They get paid to make people happy and live better; they give away food all day. What a great way to live.”

The organization holds several fundraisers throughout the year, including an annual fall food tasting that will be held on October 29 this year, at The Glasshouse in New York. Last year’s event raised enough to feed 4 million people.

The Next Generation

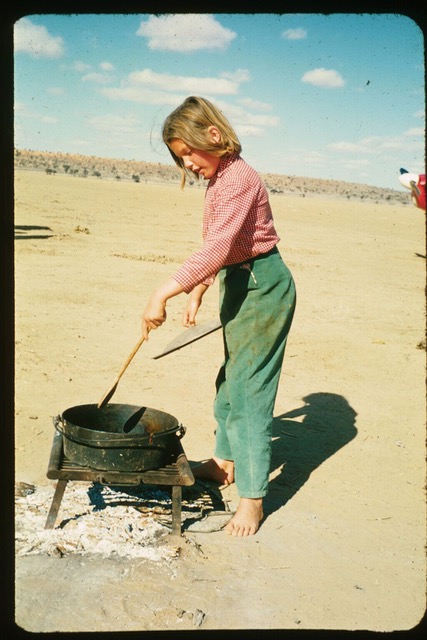

As a father of three, Mr. Zakarian has taken his own childhood experience of sharing a meal at the table and passed down the tradition. On any day he’s home, he makes it a point to cook breakfast for daughters Anna and Madeline and son George.

They’ve picked up Dad’s love of cooking. Anna and Madeline published a cookbook called “The Family That Cooks Together” in 2020, when they were 12 and 14, respectively. They also helped start a Junior Food Council for City Harvest that year.

Want to teach your kids to cook? Mr. Zakarian says it only takes one thing.

“Smells. This is why there’s a failure in modern cuisine, that minimalist cuisine: If nothing has a smell, it’s not memorable. Every memory you have of food is the smell.”

Mr. Zakarian says nothing draws a kid into the kitchen more than the aroma of something delicious. “You don’t have to ask kids to do anything. They’ll smell something, come by, and say, ‘What’s that, Mom?’ And she’ll say, ‘Well here, try it.’ I’ll say, ‘Do you want to help?’ ‘Sure.’ It’s not forcing them to do anything. It’s the memory of the smells and the clanging of pots and pans.”

Spreading the Joy

He’s also passionate about bringing those memories to other families. His cookware line, launched under Zakarian Hospitality, is designed to “make life better for the average person at home,” he said. He doesn’t focus on obscure items you might use once every 10 years, but basic, good-quality cooking tools you’ll need every day.

His television appearances aim to do the same. “I love these shows because they show people how to nourish their families,” he said. “When people watch a competition show, they love the competition, but at the end of the day, it is captivating their memory with things they want to try.” He calls it “nourishment of the stomach, but also nourishment of the soul.”

As a chef, Mr. Zakarian focuses on what he calls the Mediterranean basket, the diet from Greece and Italy. At his restaurants, “I make menus for food that I enjoy,” he said. “I just try to make food yummy for myself, and if I like it, I would say that 99 percent of my customers will like it.”

But whether he’s cooking for customers or his kids at home, his philosophy is the same.

“If you have everyone sitting around the table, that’s the real joy, that’s where everything happens—all the glances, the looks, the nuanced conversation that comes out,” he said. “If you can get them to the table, that’s the real reward.”

9 Questions for Geoffrey Zakarian

Comfort food? Steak frites.

Most beloved kitchen tool? Paring knife.

3 ingredients you can’t live without? Sea salt, chardonnay vinegar, anchovies.

Underrated ingredient? Miso.

Go-to easy but impressive dish to cook for someone? Spaghetti with lemon.

Daily wellness rituals? Work out five times a week. Don’t skip breakfast. Eat grass-fed beef, full-fat yogurt, fruits, berries. Big fan of honey and dates instead of sugar.

Favorite hobby when you’re not cooking? Golf.

Best advice for home cooks? Start learning to cook with breakfast. Eat your mistakes.

Best advice you’ve ever received? Fail up.

RECIPE: Butternut Squash and Apple Soup

RECIPE: Game Day Pork Chili

RECIPE: Middle Eastern Eggs

From Sept. Issue, Volume IV