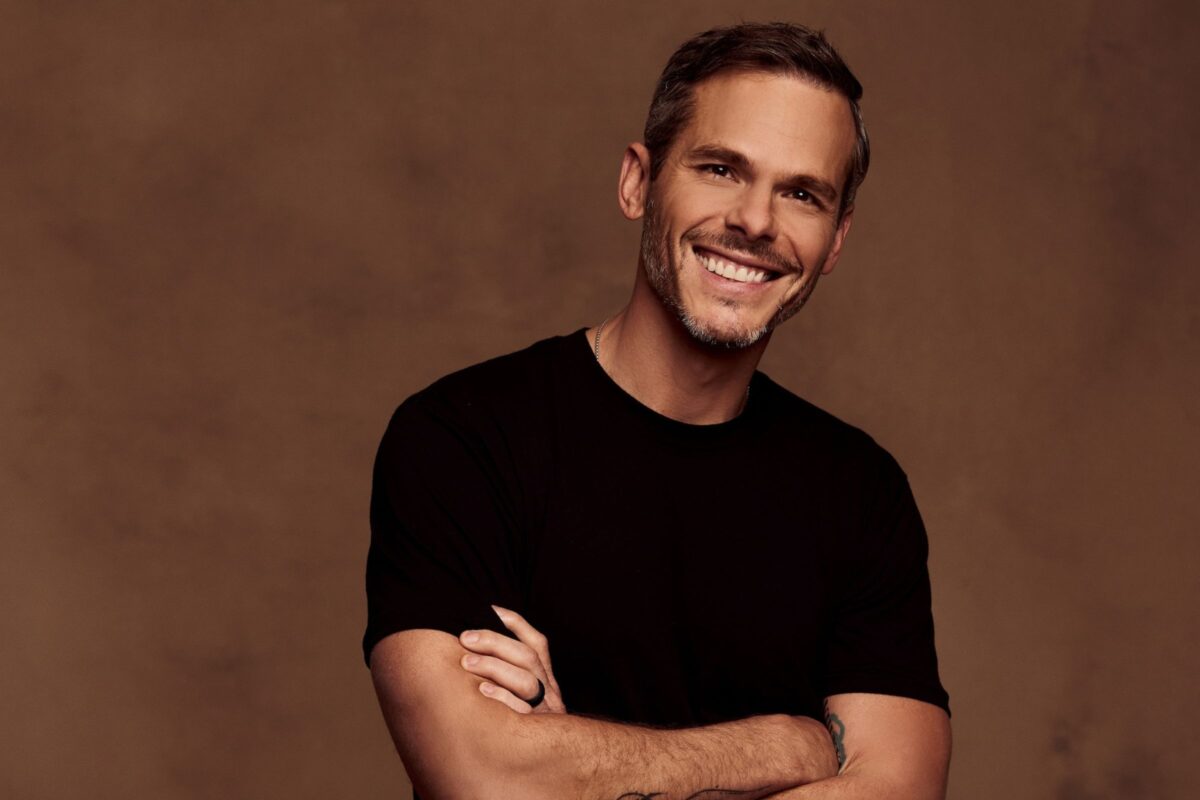

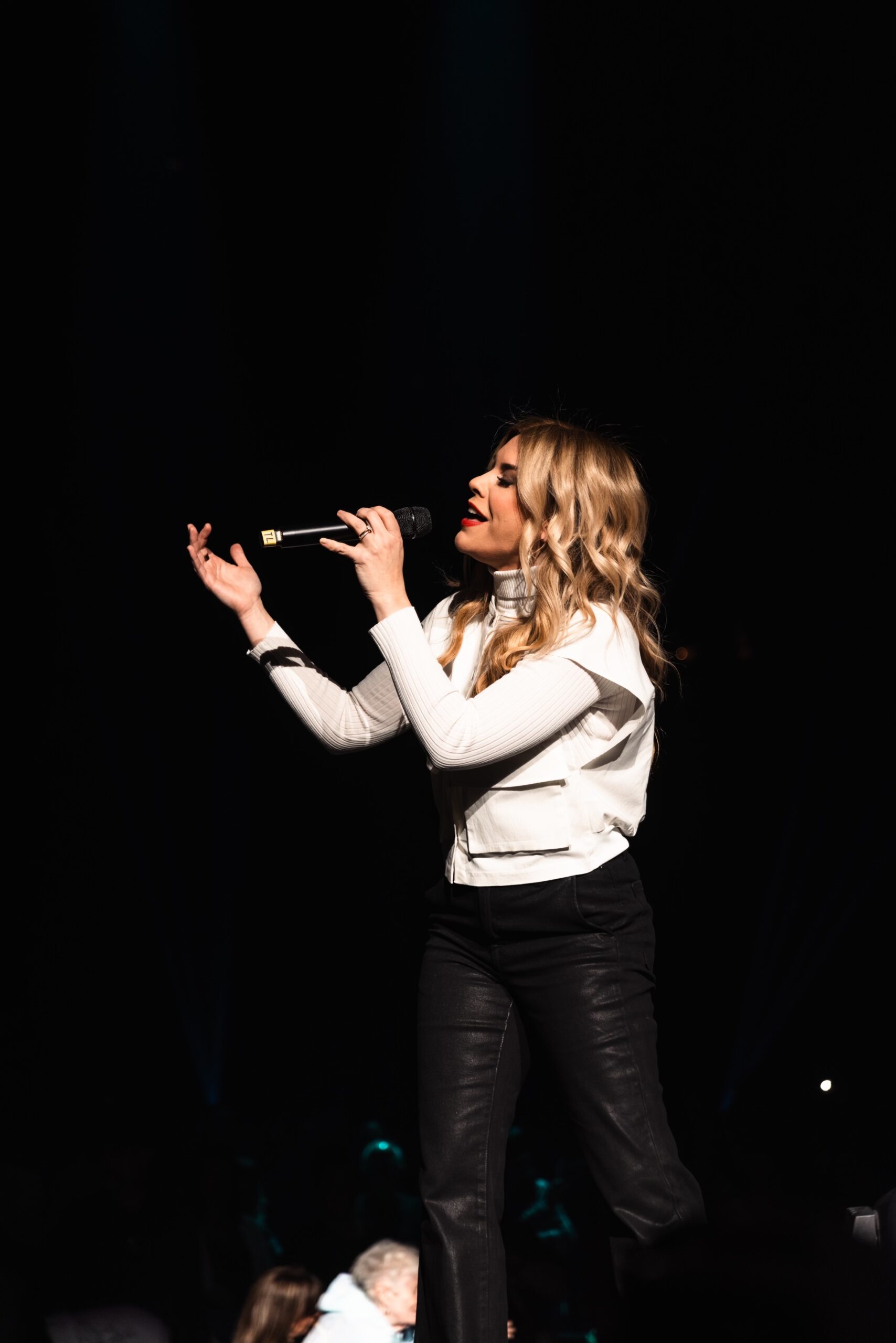

Tasha Layton has thrived since her days as a contestant on “American Idol” and a backstage vocalist for Katy Perry. After turning down a solo career in pop music, she released several successful Christian singles, including “Into The Sea (It’s Gonna Be OK)” and the smash hit “Look What You’ve Done,” which landed her on Billboard’s list of top 5 female Christian artists of the year in 2020 and 2021. She is currently wrapping up her Trust Again tour across the United States.

In this interview with American Essence, the South Carolina native shares about her life—from being mom to her kids Levi and Lyla, to launching a mental health initiative inspired by her own story. Through it all, faith and family are front and center.

American Essence: What is your morning routine like?

Tasha Layton: My morning routine is being woken from a dead sleep to chaos every morning. My children are 4 and 7, and so I may or may not have washed off my makeup from the night before, and I literally hit the ground running.

There’s no routine right now in my life, which I am sad about, but I know that will come as my kids get a little bit older. I know that I’ll fall back into a routine, but I do try to wash my face every day, but I don’t have a normal cleanser either. I mean, it’s literally just chaos and no rhythm. The only rhythm that I definitely don’t sway from is my time doing daily devotionals.

AE: Any daily wellness practices that keep you grounded?

Ms. Layton: My time in meditation and prayer every day with my Bible and my journal—that is the one that I don’t miss. I really want to take better care of myself physically, but as a mom, I haven’t been able to find that balance yet. And sometimes, for folks looking at my life from the outside in, they might think I have it all together, but I really don’t.

AE: What is something that people might be surprised to find out about you?

Ms. Layton: Before I had children, I was an adrenaline junkie. I skydived, bungee jumped, did extreme scuba diving, rafting, and other things like that. I just loved doing extreme things. And then when I had kids, I didn’t do any of it anymore, because I just wanted to stay safe for them.

AE: What is your favorite part of the day?

Ms. Layton: I love the time in the evening when I get to snuggle my kids on the couch, or read to them at night before they go to bed. That’s my favorite time of the day. My husband and I weren’t able to have kids, we weren’t supposed to be able to have kids, and so our children are miracles and huge blessings to us.

AE: What has motherhood taught you?

Ms. Layton: I learned something new about God all the time because of my kids, how much God loves us, how much grace He shows us, how much patience He shows us, ways that He knows better than we do about certain things. And, like a good parent, you’re going to give your kids what they need, not always what they want. You don’t know what you’re capable of until you become a mother, because you’re operating under extreme exhaustion and beyond the capacity you thought you had, and somehow you get it all done.

AE: What is your favorite family tradition?

Ms. Layton: One of my favorite times together as a family is when we are home from traveling and we go out for Mexican food and ice cream. We do it regularly, and it’s easy. We don’t have to think about it—we know what we’re going to get to eat. My kids love that time. They get so excited for ice cream at this age, so we really love just time together as a family, since we travel so much.

AE: What inspires you and keeps you going on tough days?

Ms. Layton: It’s a combination of two things. The first is that I feel an innate sense of calling from God to do what I do, and, thus, the grace to do it. And the second is that I hear stories every night when speaking with people after events and concerts of how my music has inspired them or changed their lives. Hearing that encouragement from them is also a big deal for me.

AE: How does your faith show up in everyday life or guide your daily decisions?

Ms. Layton: My faith shows up in every single decision I make every single day—how I respond when my kids are fighting, my tone when my husband brings up something to talk about, or how I greet the Amazon delivery person at my doorstep. It’s how I treat people. Doing what I do for a living, I have a very large team, and it’s how they feel treated—and do they feel loved? Do they sense that I am wanting the best for them?

AE: What is your ultimate goal as an artist, and how do you hope to impact others?

Ms. Layton: My ultimate goal with music is to help people connect with God, and, by helping people connect with God, that helps bring them freedom and joy in life. Those are the things that I’m aiming for every time I write a song, to connect people with Him.

AE: How does your faith influence the messages you want to convey through your music?

Ms. Layton: When you write Christian music, you are essentially teaching theology to the masses. With theology, being the study of God, you have to be very careful about what you’re writing. I want to get a theologically sound message out to the masses and to help people know and experience the love of God at a level maybe they hadn’t before. And when I’m writing a song, I have that in mind, both making sure that the song is scripturally sound and also just a healthy song. I’m not going to write about the things that other pop artists write about. I’m going to write about heart issues and keep God at the center of it all.

AE: Where do you find inspiration for your music?

Ms. Layton: The biggest inspiration I’ve had so far has been my own experience—the low points of my life, the struggles, the honest questions I’ve had—but as I continue to do what I do on the level that I do it now, it’s also being inspired from the people who come to my events and tell me their stories. Other people’s stories have been very inspiring for me over the last year, and I definitely consider those stories when I’m writing music.

AE: What songs have you gotten the most feedback on?

Ms. Layton: Probably one of my biggest songs to date is a song called “Into the Sea,” and I think people have really gravitated to that song because the chorus says “It’s Gonna Be OK.” And we live in such a season as a culture of anxiety and fear, and hearing the message “It’s gonna be OK” is very important.

As a person of faith, I don’t believe that just because we have faith, our life is going to be easy or free from distress or obstacles, but I do believe that God’s presence will always be with us, and that our faith sees us through those things and walks through those things with us. That song has definitely been a huge anthem for people. And then I have another one called “Look What You’ve Done.” That’s my life’s testimony in a song. That one has become an anthem for a lot of people as well.

AE: Who has had the most significant influence on your life or career?

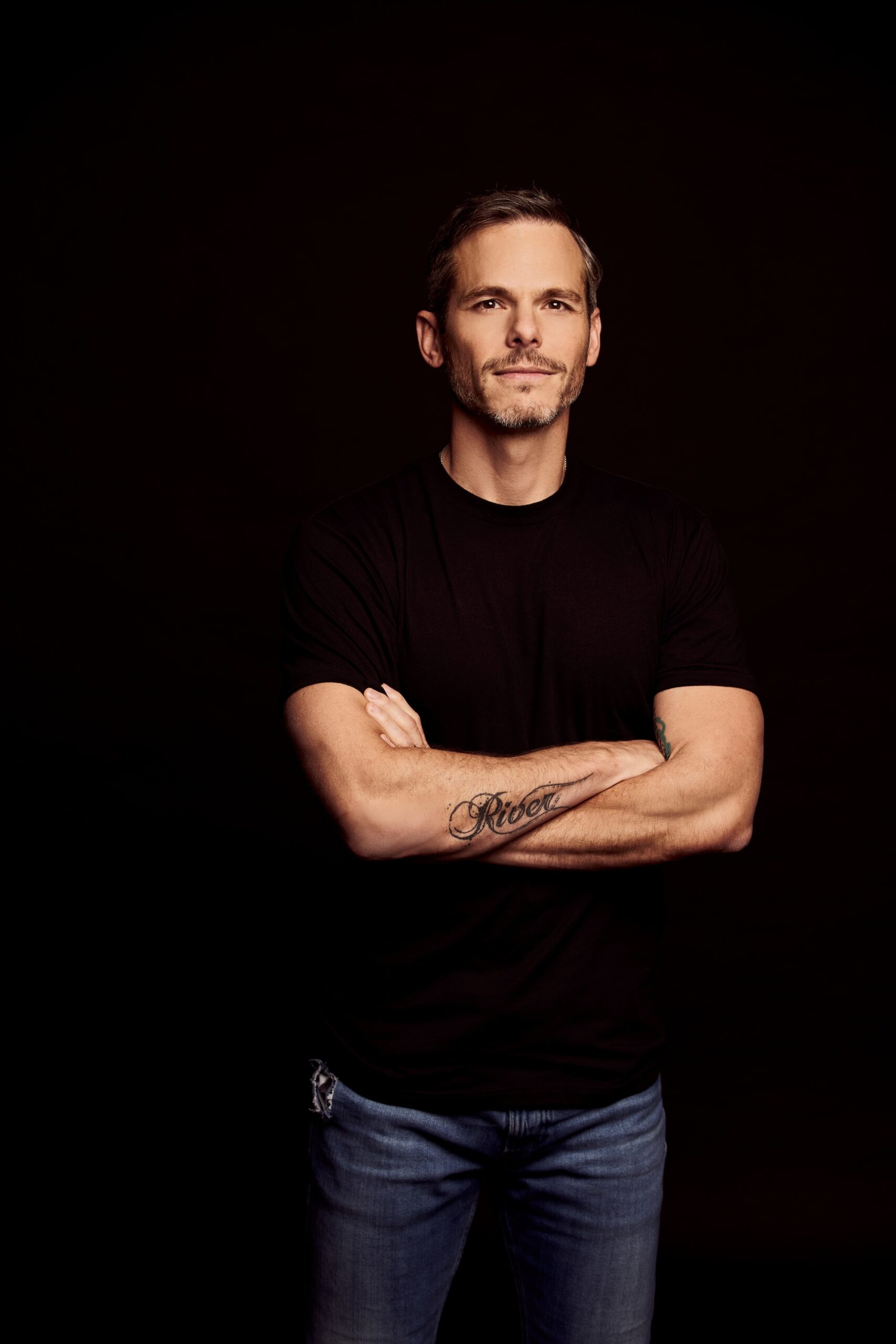

Ms. Layton: My husband has had the most influence on my career, because he is the one who believes in me and pushes me to do all that God has called me to do, and I can’t fake it in front of him and get out of anything. He’s gonna be that voice to say, “You can do this.”

AE: What is the most valuable piece of advice you’ve received in your career, and how did it impact you?

Ms. Layton: When I was a young girl, my mom told me, “Tasha, be who you’re supposed to be, and you will become exactly who you’re supposed to become,” and she said, “Be who you’re supposed to, and you’ll do exactly what you’re supposed to do.”

I think when we focus on our character and our internal integrity and self, somehow, the externals just handle themselves—jobs and open doors and all of that. It handles itself when you focus on your character and on being more like Christ. And I’ve carried that with me my whole life.

AE: If you could sit down with your younger self at the start of your career, what advice would you give her?

Ms. Layton: I wish that I would have lived with the fear of God and not the fear of man. I was so concerned with what people thought of me that I wasn’t living courageously or vulnerably. It wasn’t until I knew how loved and special I was, and that God feels that way about every single person on this planet. It wasn’t until then that I truly stepped out courageously into what I felt like I was supposed to do in life, because I knew that I didn’t have to be afraid of what people thought.

AE: What projects are you most excited about right now?

Ms. Layton: I have three things I’m very excited about right now. One is a live worship record that is releasing this year. And then, I also have a full-length studio project releasing as well. The third thing that I’m very excited about is, I began a Christian mental health initiative in 2024 called Boundless.

It was really birthed from my own mental health struggle because I have a suicide attempt and depression in my history, and I went through a process with God and my therapist that really got me through and set me free from all of that. It was so special that I wrote a book about it to help people walk through that same process, to experience the kind of freedom that I had experienced. The book turned into a workbook that turned into a leader guide, and then I wrote a kids’ book, and now it’s an online course. My aim is to help people reach a sense of holistic health in their life that’s not just, you know, taking a pill for everything or praying it away. It’s this balance of what we need in every area of our life to be whole and healthy. But it began out of my own process of freedom, from lies I believed when I was a kid about God, about myself, about other people. We’ve put a lot of work into that this year, and I believe that the music in what we’re doing is working hand in hand to help people find that freedom.

AE: What is a dream project or collaboration you haven’t tackled yet, but hope to in the future?

Ms. Layton: I would love to build an intensive counseling center where people can escape and go explore their own history and get healed up from past wounds and trauma.

AE: How does your faith influence the messages you want to convey through your music?

Ms. Layton: When you write Christian music, you are essentially teaching theology to the masses. With theology, being the study of God, you have to be very careful about what you’re writing. I want to get a theologically sound message out to the masses and to help people know and experience the love of God at a level maybe they hadn’t before. And when I’m writing a song, I have that in mind, both making sure that the song is scripturally sound and also just a healthy song. I’m not going to write about the things that other pop artists write about. I’m going to write about heart issues and keep God at the center of it all.

AE: How does your faith show up in everyday life or guide your daily decisions?

Ms. Layton: My faith shows up in every single decision I make every single day—how I respond when my kids are fighting, my tone when my husband brings up something to talk about, or how I greet the Amazon delivery person at my doorstep. It’s how I treat people. Doing what I do for a living, I have a very large team, and it’s how they feel treated—and do they feel loved? Do they sense that I am wanting the best for them? Other people’s stories have been very inspiring for me over the last year, and I definitely consider those stories when I’m writing music. It handles itself when you focus on your character and on being more like Christ. And I’ve carried that with me my whole life.

From March Issue, Volume IV