It was Ray Whitley who started the excitement. Throughout the 1930s, Whitley traveled with the World’s Championship Rodeo, providing musical entertainment with his band, the Six Bar Cowboys. In 1937, he prodded the Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Co. to develop a “super jumbo” instrument, one that could go lick for lick with the nearly 16-inch-wide, rosewood-and-mahogany Dreadnought guitar issued by C.F. Martin & Co.

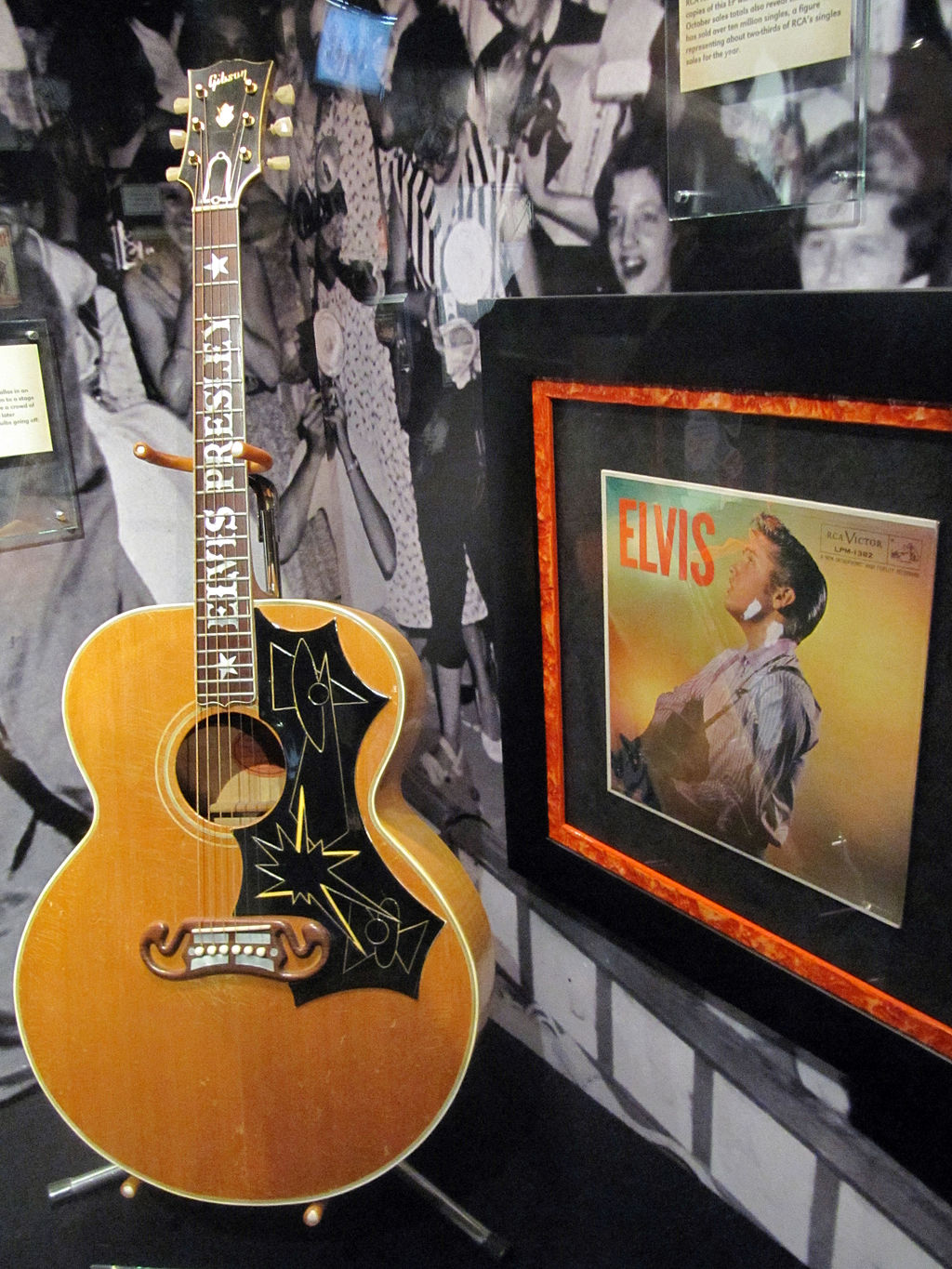

“Of course, what somebody at Martin saw, and what no one at Gibson apparently did, was that players were forsaking banjos for guitars and demanding louder instruments,” wrote Walter Carter in his history of the Gibson company. There was no other way to match the volume of the singer and microphone. Playing live dates, Gene Autry, a star at Chicago’s WLS radio station, was already strumming an elaborately ornamented Martin D-45, which replaced the smaller Martin that had been stolen along with his Buick the year before. Whitley’s demands of Gibson resulted in a 17-inch-wide body with a mosaic pickguard and the slogan “Custom Built for Ray Whitley” inscribed on the headstock. The Super Jumbo 200 took its name from its generous size and steep list price: $200 (a 1938 Ford could be purchased for just over three times that amount). After World War II, the model would be known simply as the SJ-200, and Elvis Presley cradled one when he appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1957.

“The Gibson-made instruments were louder and more durable than the competitive, contemporary fretted instruments, and were the go-to instruments demanded by players of the day,” explained ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons in an email.

Whitley carried his SJ-200 to Hollywood, where he wrote “Back in the Saddle Again” for the cinematic mystery-romance “Border G-Man.” Meanwhile, Gibson made a dozen more SJs for key influencers. Autry bought two at the discounted price of $150 each, and his biographer, Holly George-Warren, wrote of one guitar that it was “embellished with a two-tone mother of pearl border; horses and bucking broncos inlaid with pearl; and his name writ large alongside horseshoes inset on the fingerboard.” It was a spectacular instrument and showpiece, indeed, making a lasting impact.

In 1939, Autry recorded his version of Whitley’s tune and adopted “Back in the Saddle Again” as his enduring theme song. Heard today, the lyrics still evoke feelings of truth and triumph, but cowboy singers would soon fall out of fashion. The music made by electric guitars took over radio airwaves. Autry finished his career with landmark recordings of holiday songs, namely “Here Comes Santa Claus,” “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” and “Peter Cottontail.”

The integration of Gibson guitars into the upper echelons of popular music deserves some explanation. The company’s founder, Orville Gibson, had migrated from his native New York state to Kalamazoo, Michigan, by 1881, when he was 25 years old. After more than a dozen years as a clerk in a shoe store and a restaurant, he started manufacturing musical instruments. In his small workshop, he made mandolins from a patented design. The patent application of 1895 said existing instruments were made of too many parts, “to the extent that they have not possessed that degree of sensitive resonance and vibratory action necessary to produce the power and quality of tone and melody.” He boasted of having achieved “a sound entirely new to this class of musical instruments.” The first Gibson catalog offered a family of mandolins for the popular mandolin orchestras, as well as round- or oval-hole guitars and harp guitars with 12 or 18 strings. Five stages of ornamentation, from plain to fancy, were available.

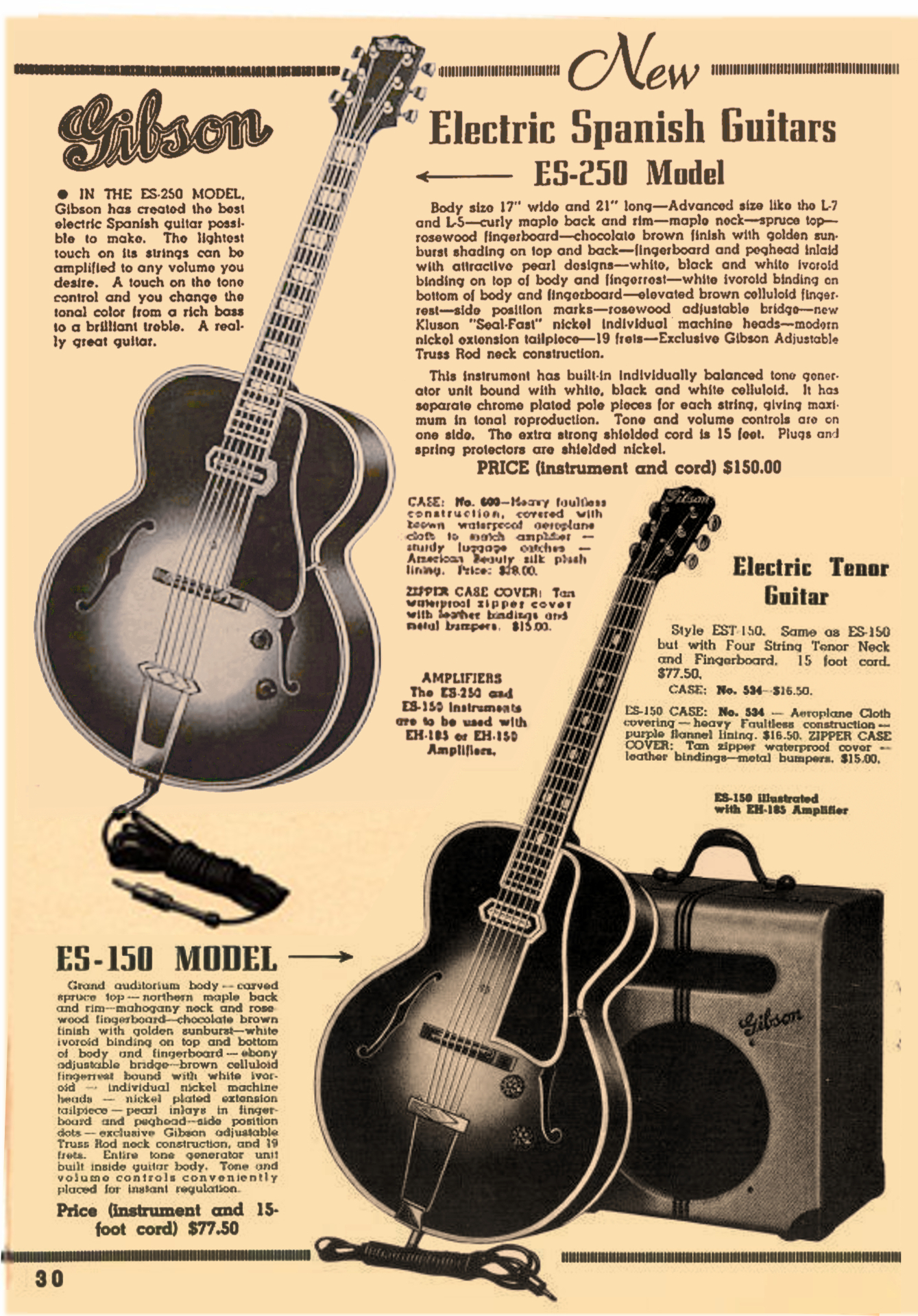

By 1902, an investor group took over Gibson’s enterprise, and the next year the founder—who had become a consultant for the company—quit, in order to teach music and collect royalties. Eventually, Gibson returned to New York; he died in 1918. His namesake company adopted an innovative marketing approach, turning music teachers into salesmen and letting customers pay small monthly installments. The Gibson banjo was introduced, but the 1911 L-4 and 1923 L-5 guitars were better fits with Jazz Age outfits like Duke Ellington’s Washingtonians at a time when people were losing their heads dancing the Charleston. With the finest materials and craftsmanship, the 1934 Super 400 extended the trend of successful rhythm instruments. Gibson’s first electric, the hollow-body ES-150, made its debut in 1936 and was popularized by the ill-fated jazz player Charlie Christian. Extolling “electrical amplification,” Christian showed the world how to perform a proper solo, before he died—too young at 25—of tuberculosis.

While worthy competition came from the 1950 Fender Telecaster and 1954 Stratocaster—solid-body electrics made in Southern California—Gibson made a wily move in advance of the era of rock ’n’ roll and electric blues: In order to avoid the disdainful label of “plank” guitar, the solid-body 1952 Gibson Les Paul was developed with collaboration from Les Paul (Lester Polsfuss), who was a master player and something of a mad scientist. The guitar that bore his name had a carved maple top with no sound holes, and the gold color was intended to disguise a trade secret: the mahogany back. Like Orville Gibson’s mandolins, the new guitar was an innovative departure and an instant classic. The challenge was to figure out what to do with it, but players stepped to the fore. Bluesman John Lee Hooker, to name one, extracted grit and passion from his Les Paul. Billy Gibbons dubbed his own 1959 example “Pearly Gates,” explaining that the guitar “possesses those rare qualities found in a precise combination of elements which miraculously came together on that fateful day of fabrication.”

Renamed Gibson Guitar Corp., and now Gibson Brands, Inc., the company moved operations from Kalamazoo to Nashville by 1985, with acoustic guitars produced in Bozeman, Montana, since 1989. The company has experienced ups and downs in conjunction with fickleness in the national economy and the guitar industry—even restructuring in Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2018. However, the pandemic has brought about a surge in guitar sales—“Did Everyone Buy a Guitar in Quarantine or What?” asked Rolling Stone—putting the company in a good position to capitalize on the upswing. Gibson guitars continue to lend their great sound and seriousness of intent to new musical acts. And it all started with Orville Gibson and his carving tools in Kalamazoo.

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.