In spite of her “made in the USA” appeal, being an American sculptor is not something Emily Bedard was always celebrated for. “When I first entered the molding industry, I had people who questioned my ability because I wasn’t French or European,” recalled Bedard. “I would produce a really strong structural element, and the salesman would sell it as if it was a French artist who made it.”

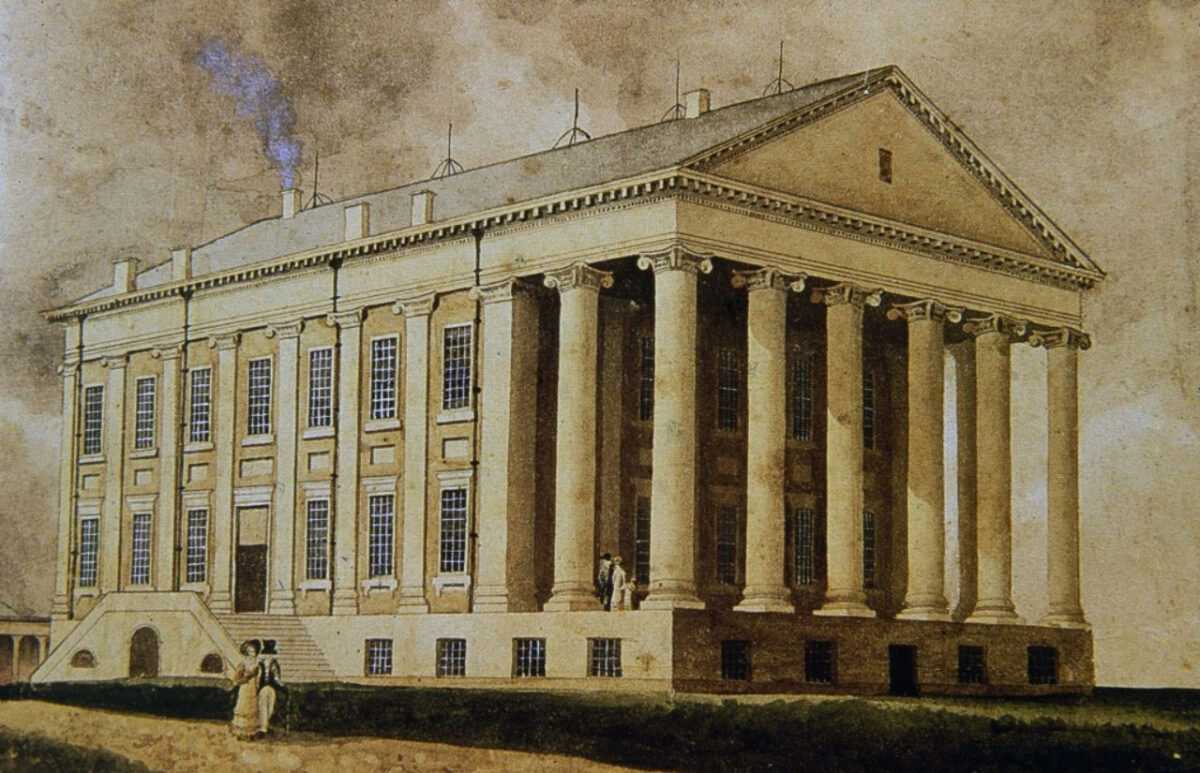

Clients, in fact, sometimes wouldn’t trust Bedard because she was American. “There is a general stereotype that Americans don’t have roots in traditional craftsmanship, that traditional American art has to come from Europeans,” she said. “That’s ridiculous,” she added, “since America has such strong roots in classicism.”

At age 34, this native-Vermonter-gone-New-Yorker has undoubtedly proven that American hands are creating ageless, epochally awe-inspiring works of art that our country can be proud of. Bedard has won multiple awards in her young life, including the highly coveted Edward Fenno Hoffman Prize from the National Sculpture Society, and the Award for Emerging Excellence in the Classical Tradition from the prestigious Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, which Bedard says has been a tremendous support for her continuing education as a sculptor.

Her early works include the breathtaking 6-foot Liberty statue at the 1876 Soldiers and Sailors Monument, which graces the highly celebrated Seaside Park in Bridgeport, Connecticut; the life-like clay bust of U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy, and the pair of gold eagles that flank the central clock at the Edward Kennedy Institute in Boston. Bedard has also had quite the A-list of private clients, including Mark Wahlberg, Yoko Ono, Oprah Winfrey, and Uma Thurman.

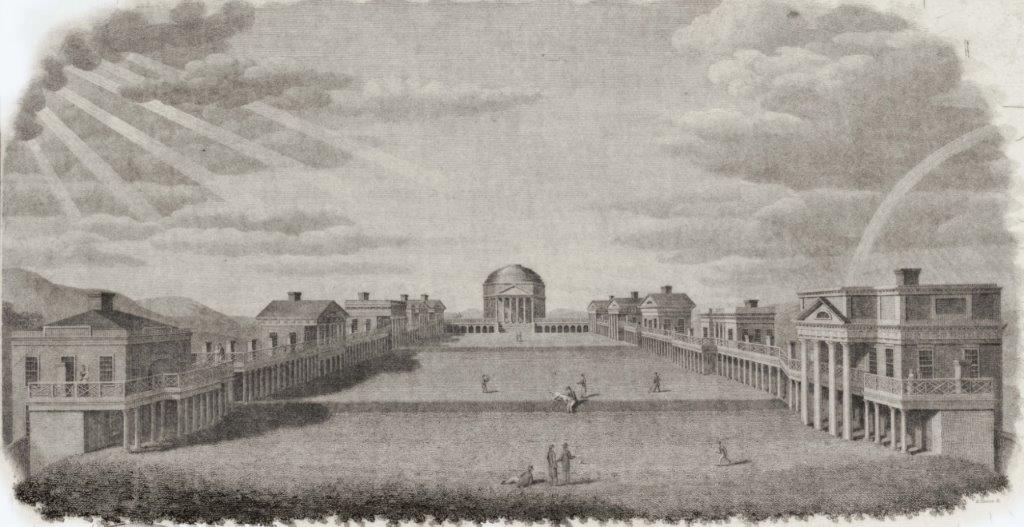

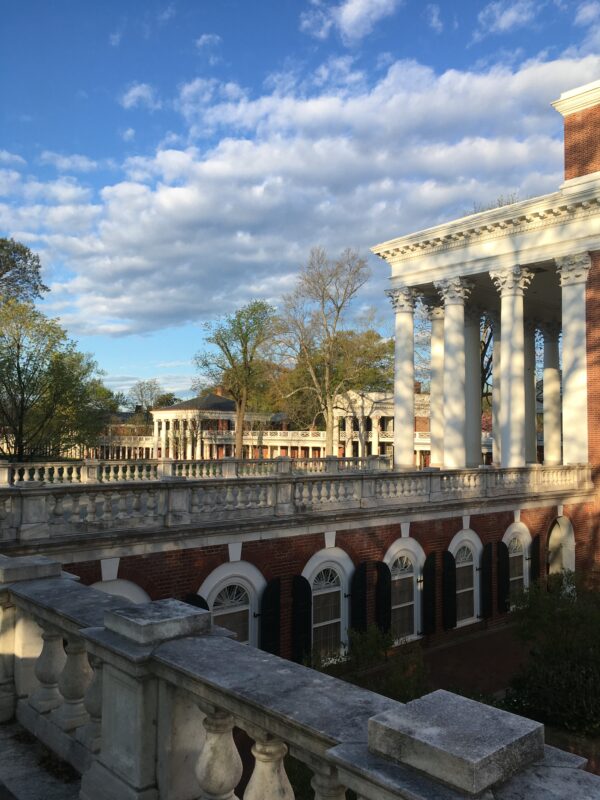

She is currently working on a piece for the National Desert Storm and Desert Shield Memorial, to be built at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. This sizable memorial will occupy about 200 feet on the sacred public pathway, and will feature American soldiers and traditional military armaments, such as tanks and planes, with a desert background. The sculpture was commissioned by the National Desert Storm War Memorial Association, and it will be the first national memorial to represent the fierce conflict that soldiers faced in the Liberation of Kuwait campaign 30 years ago.

Bedard hopes to break ground sometime in 2022, and when she does, she’ll be working right down the street from the Lincoln Memorial, the fabled work of one of her idols, Daniel Chester French. Like Bedard, French was a native New Englander, who drew special inspiration from American patriotism.

Bedard, admittedly not your typical millennial (she barely touches a computer), had always wanted to serve in the military, a bygone aspiration that regrettably went unfulfilled. “I always had this strong desire to give back to this country,” reflected Bedard. “I met a lot of pushback to do that, and wasn’t sure how I could use my limited abilities to do that, but then I figured out that public monuments can speak to the human spirit and remind people of the achievements and honors of the people who have served our country.” She added that this gave her “a deeper motivation with the abilities I had been given.”

In furthering her commitment to promoting Yankee craftsmanship, Emily purposely searched out an American art school: to be specific, a small, charming one in New England, as she describes. She attended the Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts, located in a quintessentially quaint seaside town in Connecticut. “I chose this school because it was very evident that when graduating from there, you were going to come out with very traditional skills,” said Bedard.

She also wanted to bring credence to the profession as being more than a stigmatized starving artist pursuit. Born to two artists and introduced at an early age to artist colonies like Maine’s Monhegan Island, Emily also had a strong interest in the sciences, specifically engineering. And so, to become a true sculptor, Emily molded the two together, and found her niche in ornamental work for high-end architecture.

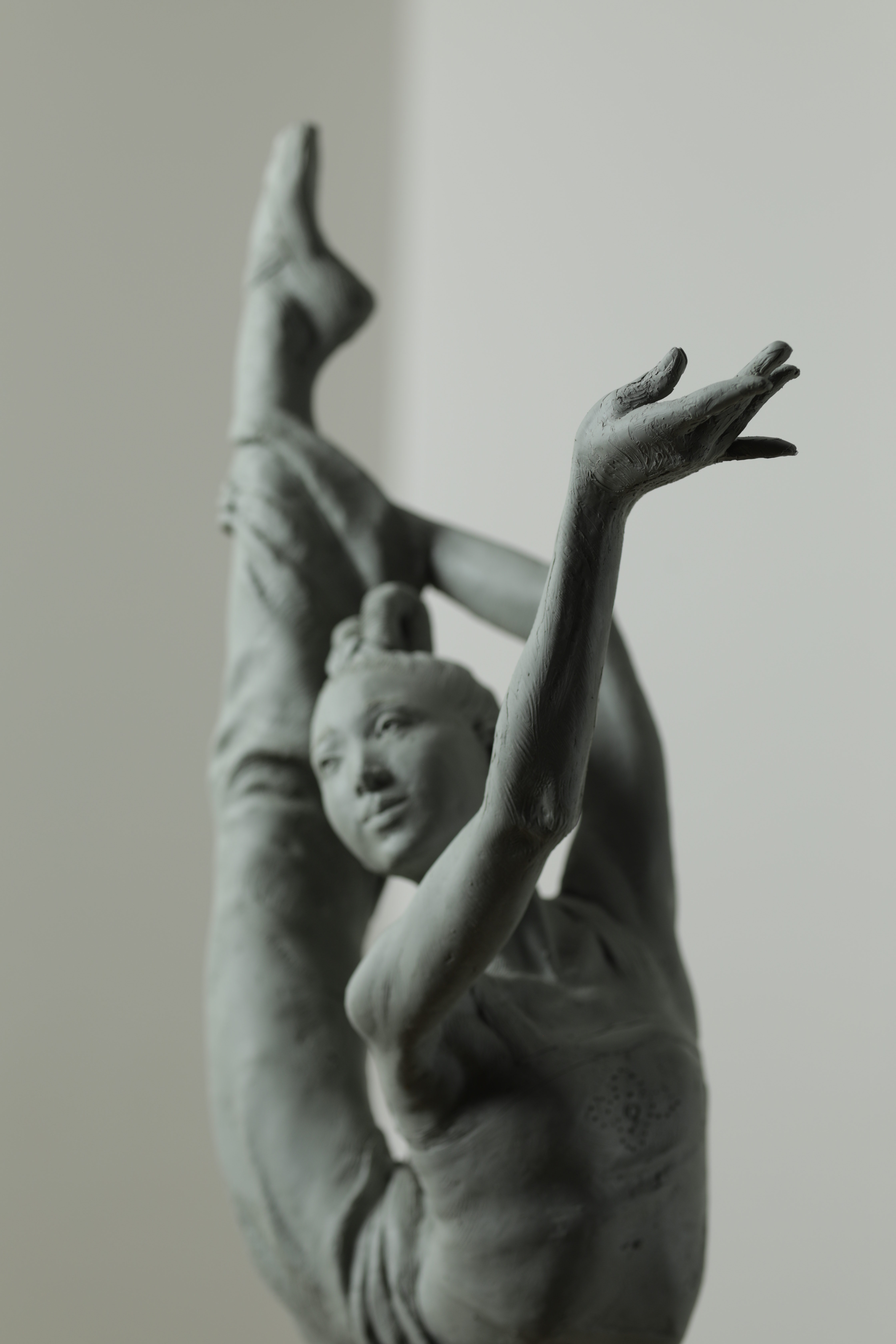

Today, in addition to running her art studio in the hip Greenpoint Historic District of Brooklyn, Bedard is the creative director at Foster Reeve & Associates, a group of globally-renowned custom designers of ornate custom plaster molding. Whether it’s fancy cornice molding on a mansion, or the sword of a soldier, Emily is obsessively preoccupied with unassuming allegorical details. She has an undying love for sculpted “drapery.” She explained that she has always really liked drapery “like that on a classic Roman statue, the way cloth falls on a figure and almost appears to cling to the form, as if it is real flesh.”

When colleague Meredith Bergmann asked her to assist with the making of the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument on Literary Row in Central Park, Bedard was, of course, excited to be a humble part of that creation. It is an imposing 14-foot statue, which features American rights activists Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton having a conversation. She described it as a “long overdue representation of women.” There was also this added bonus for Bedard: “I got to do the curls of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s hair!”