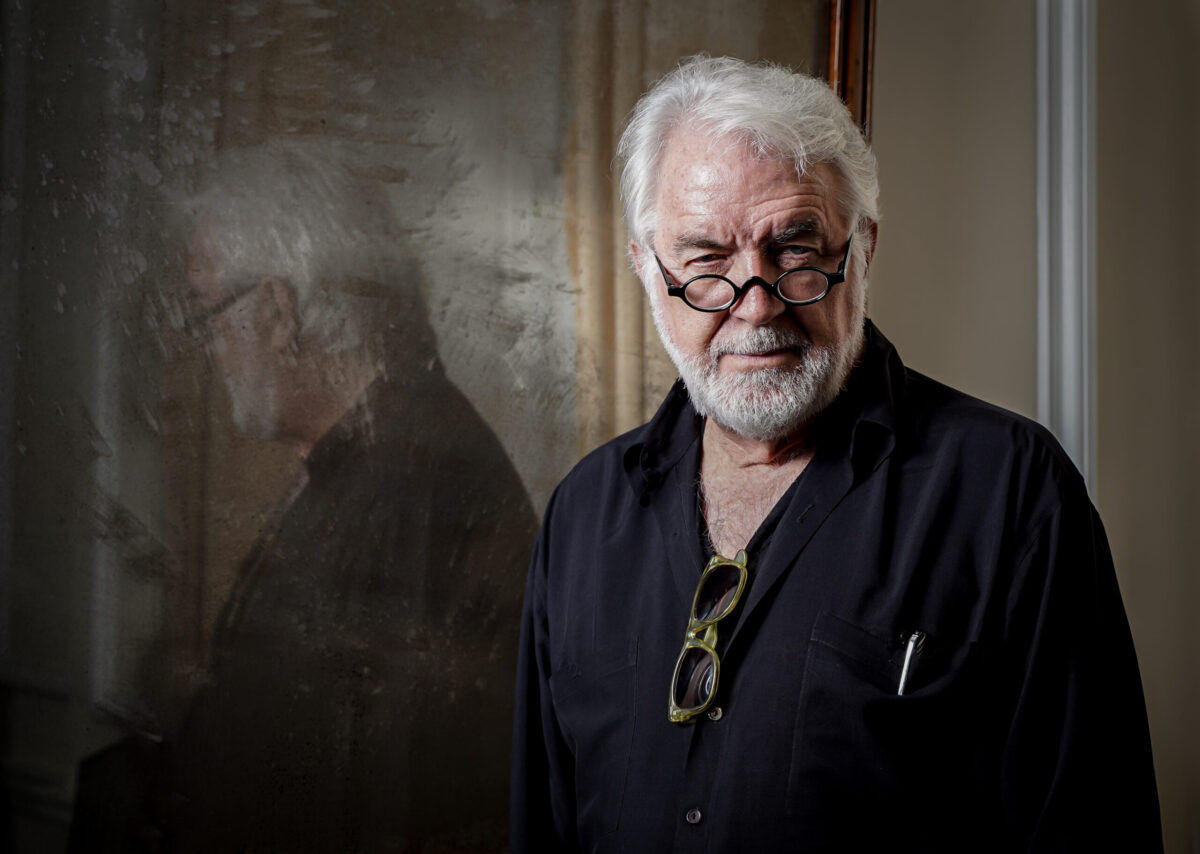

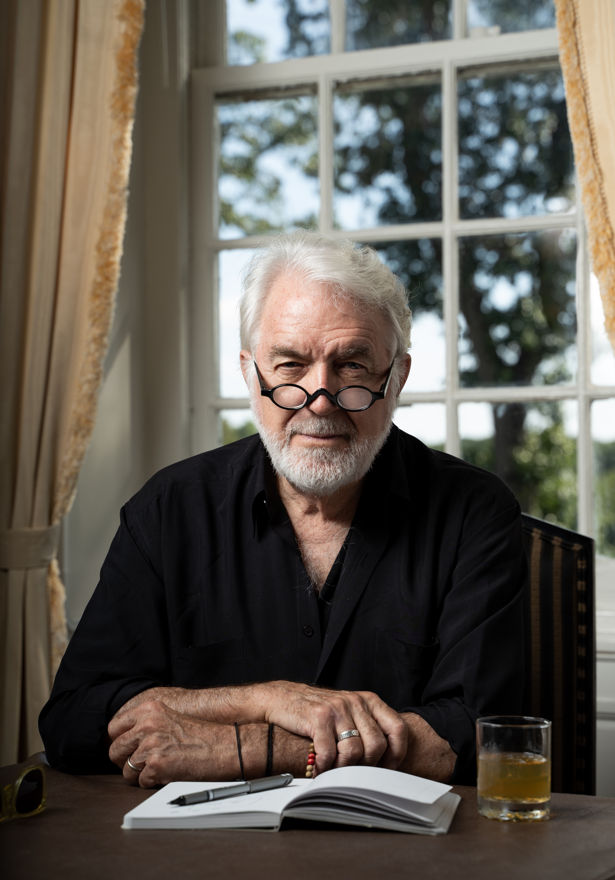

James Von Allmen Hart, lovingly referred to as “JV” by his family and protégés, is the creative force behind several of our nation’s most prominent family films, including “Hook,” “Tuck Everlasting,” “Dracula,” and “August Rush.” Well before he began his career as a Hollywood screenwriter, he grew up on drive-in movies and Saturday matinees in Fort Worth, Texas. His whimsical childhood adventures and deep connection to his family helped to shape him into the great creative that he is today.

In 1952, when JV was 5 years old, his father built a two-story Cape Cod house overlooking several acres of land, called “the field” by him and his brother. “It became our fantasy world, our Neverland,” said JV. “We built forts, tree houses, slayed dragons, buried and unburied treasure. It was literally a field of dreams for the imagination.” It would be the place where, at only eleven years young, he would film his first eight-millimeter movie.

Every Saturday at 10 a.m., JV’s mother would drop him and his brother off at the Gateway Theater, a classic Art Deco style cinema with a large marquee and tall neon sign. “For 25 cents we got a truckload of cartoons, two serial installments like Flash Gordon and Commando Cody, and then a double feature,” said JV. These Saturday mornings would serve as the foundation for his future creative endeavors in the film industry.

There is something so extraordinarily authentic about the characters that JV dreams up. “There is always part of me in everything I write,” he said. Though JV attributes this iconic authenticity to letting his characters, rather than his pen, take the lead, it is obvious that there is a tremendous connection between writer and character. Take, for example, Peter Banning of Hart’s quintessential swashbuckler adventure film, “Hook.” When asked which character in the picture he relates to most, it’s no surprise that it is Peter Banning, the grown-up version of Peter Pan. Banning’s childlike wonder is nearly a mirror image of JV’s own disposition.

“Certainly the grown-up Peter Banning who pursued success at the expense of his family came from my personal fears about losing [my] imagination as an adult and missing [my] children’s milestones.” This idea deeply resonated with Dustin Hoffman, Robin Williams, and Bob Hoskins, who marvelously acted in “Hook,” and Steven Spielberg, the film’s director.

Always on the lookout for a good idea to turn into a story, JV credits his family with providing him with the most inspiration. After all, it was a game of “What If” in 1985 at the dinner table with his son, Jake, then 6 years old, that inspired JV to develop “Hook.”

“This is now part of our family mythology as Jake, now grown up and one of my writing partners, claims he does not recall this evening. It went something like this:

Jake: Hey Dad, did Peter Pan ever grow up?

Dad: Now that’s a really dumb question. (Good Parenting.) Of course he didn’t grow up. He was the boy who couldn’t grow up.

Jake: (Defiant.) Yeah, but what if Peter Pan grew up?”

As soon as he asked the question, something clicked. Jake had unlocked the code of the Peter Pan story that so many talents in Hollywood had been trying to crack.

“We cobbled together the story based on Jake’s innocent and brilliant question. Captain Hook would kidnap grown-up Peter Pan’s kids and force the adult Pan to return to Neverland with all his adult hangups, and having forgotten how to fly (since all adults do), and having to face his old nemesis Captain Hook in order to save his kids.”

The next day, JV wrote a story treatment and called his agent, who then shopped the project around. Every producer and studio passed. The following years were misery for JV as “Hook” was, in his own words, “the best idea [he] had ever stolen from [his] kids.” His family remained ever supportive; they tried lifting JV’s spirits by gifting him with Peter Pan themed presents at holidays and birthdays.

Finally, the year 1989 brought a break. A producer read the script and believed it to be one of huge potential. The script was then taken directly to Robin Williams and Dustin Hoffman, who attached themselves immediately. And the rest is history.

“Hook” went on to generate over $300 million at the box office and is globally known as one of the most exemplary American family films of all time. He explains, “I never would have written ‘Hook’ had I not been a father with Jake and Julia to inspire me.”

JV is constantly preparing new content and brainstorming new ideas in order to bring more joy to the world. Of all the lines he has ever written, one of his favorites is, “Music is proof that God exists in the Universe.” This comes from his Oscar nominated film, “August Rush.” The picture traces the life of a boy (played by Freddie Highmore) who uses his musical talent as a clue to find his birth parents.

When reflecting on the important themes that are artistically woven into his works, JV believes Americans should pay most attention to “Tuck Everlasting.” The story of Winnie Foster, a girl on the cusp of maturity who must ultimately decide to live forever or let her life continue as planned, instills in the audience a sense of the importance of a life well lived on one’s own terms. “Don’t be afraid of death, be afraid of the unlived life,” said JV. “You don’t have to live forever, you just have to live.”

Rachael Doukas and Laura Doukas are sisters and filmmakers currently working their first feature film, “The Ryan Express,” based on their award-winning short, “Rocket Man.”