About an hour outside Montgomery, Alabama, there are seven acres of green fields, carefully grafted fruit trees, a garden, and natural woodland. Here, deer, elk, squirrels, rabbits, quail, ducks, wild turkeys, and doves live and forage, eating the acorns dropped by the oaks, grazing freely in the fields, and enjoying the fruit from the trees. This woodland, these fields and trees, are especially for them. The people who own this land deliberately cultivate it so that the wild animals can live healthy lives here, as they firmly believe that “we all can share.”

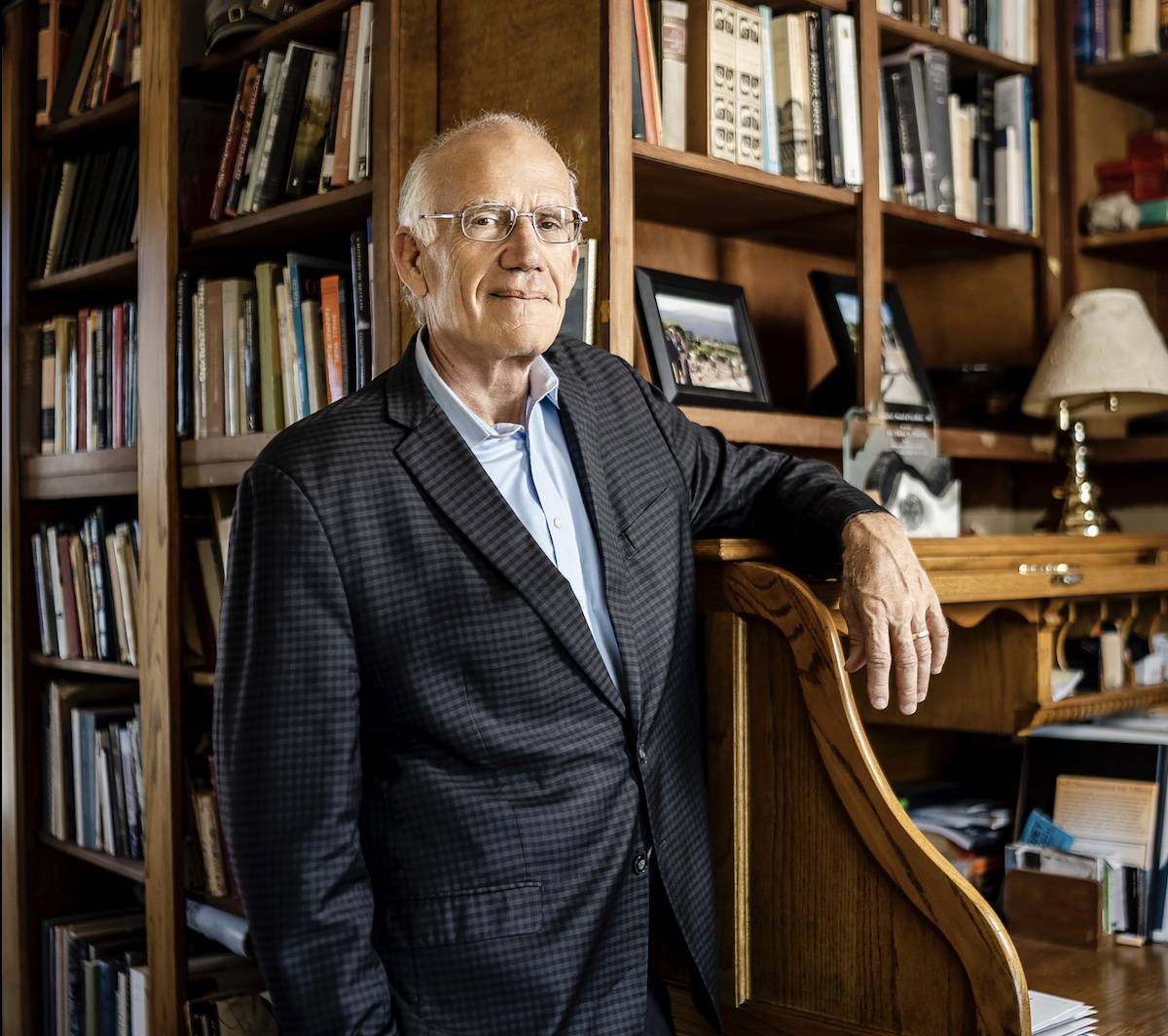

Stacy Lyn Harris and her family steward this land. They live about 45 minutes away, on an acre of land 10 minutes outside Montgomery, and they visit their wildlife sanctuary every weekend. All the meat they eat comes from their own hunting and fishing on their property, and all their vegetables come from their gardens grown near their house. They also raise chickens, and for a while they kept bees.

For Harris, her husband, Scott, and their seven children, “our sustainable lifestyle is about stewardship,” she said. Guided by her faith, her goal is to live in harmony with nature and without fear, she said, because she knows “we could survive.”

Now, Harris is an expert in her field, speaking about her approach to living off the land at homesteading conferences and on podcasts and interviews, as well as hosting “The Sporting Chef” show on the Sportsman Channel, which she has appeared on for the last 10 years. She’s written best-selling books on sustainable living and cookbooks on how to make venison delicious; her latest is a book about homeschooling, set to be published this year. In all, she estimates she has reached more than half a million people through her books and blog, and more through the show.

At the beginning of her journey, however, “it was kind of an accidental sustainable lifestyle,” Harris recalled. Her husband’s passion for hunting was the unlikely gateway.

An Unexpected Path

Harris grew up in Montgomery with her mom and step-dad, and they “went to the store for everything,” she said. She had something of an antagonistic relationship with hunting when she was younger: “My dad lived in the country and he hunted and fished, but I didn’t spend a ton of time with him. He was never there when I went to visit, and I had this aversion to hunting.”

During college, however, she met Scott. “I married this guy who is the biggest hunter you ever met in your life,” Harris said. “When we were dating, he would go out every single day of the hunting season, and he would do that now if he could.” In their early marriage, they struggled because “I felt in competition with the hunting,” she said. Eventually, “I felt a tug in my heart going, ‘You know what, you can choose to be happy here and get on board, or not.’” So, Harris said, “I did.”

She quickly discovered “why women weren’t involved in this at all.” It was because, she said, “they didn’t like the meat. They didn’t know how to cook it, and there weren’t any beautiful cookbooks.” Overcooked wild game, she noted, tastes horrible.

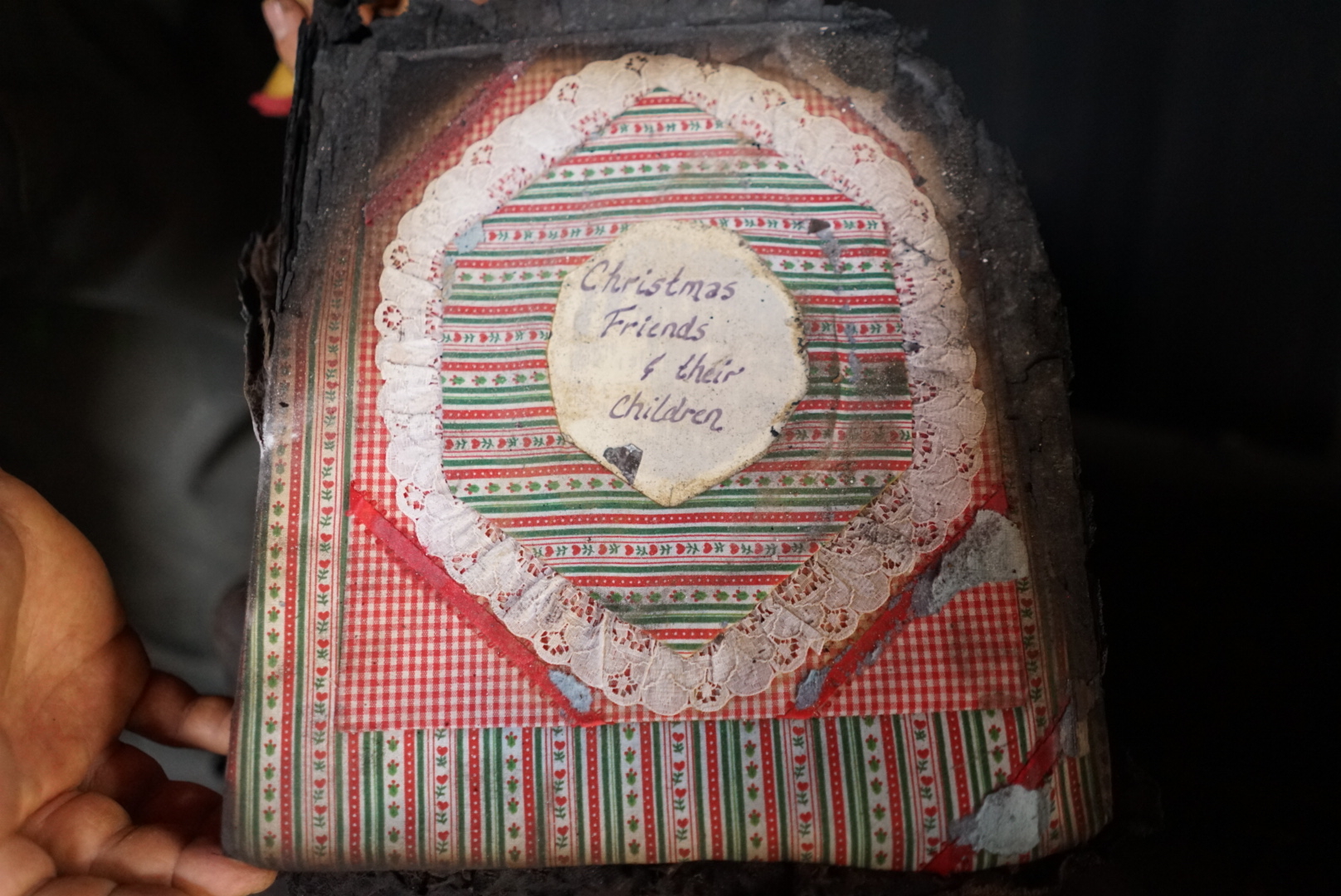

Harris gave herself three months to learn how to cook the meat well. “If I’m going to eat something, it has to be really good,” she explained. She went to antique cookbooks and recipes from times when people “had to deal with their old roosters, their hens who weren’t laying anymore, tough wild turkeys, grass-fed beef.” She learned the old techniques for handling meat that doesn’t have a lot of fat—such as braising, which cooks tough meat long and slow, allowing the fibers to relax—and marveled at how good it could taste. Eager to share her knowledge, she wrote her first cookbook, “Tracking the Outdoors In,” published in 2012.

From there, their path forward seemed to naturally unfold. “Scott hunted and we had all this great meat. Then we said, ‘Why don’t we start a garden and have vegetables, too?’” Next, they added chickens to the plan. “We didn’t talk about it a whole lot,” she said. “I thought Scott was just doing projects with the kids, building chicken tractors,” perhaps as part of their homeschooling, but one morning at 6 a.m., she got a call from the post office, and “They had chirping birds for me!”

And so it went. They now have about 50 chickens—when they aren’t being raided by coyotes—“and then we started bees, and we made a bigger garden, and we started grafting fruit trees, and we saved our seeds,” Harris said. The family has a well for water, hunts from their land, fishes from their ponds, and gathers vegetables from their gardens.

Educating and Empowering Others

Now very passionate about hunting, Harris explained that “hunters are such conservationists. They’re seeing how to manage the wildlife so they don’t get overpopulated or underpopulated, and they’re out there seeing the diseases so we can keep our wildlife healthy.” Hunting is also economically feasible for a family—“one deer will get you through about 40 meals,” Harris said. As part of the homesteading movement, she occasionally speaks at conferences to educate people about sustainably incorporating hunting and fishing into their lives—“and I teach them how to cook it to make it really good.”

Harris is proudest that she and Scott have “taught our children that they can survive, they can make it, and they are able to do it, all of it—the hunting, the cooking, the gardening,” she said. By homeschooling her children, she’s been able to build education into their way of life, so that they learn for learning’s sake. “They may never need it, they may never have to be self-sustaining, but because they can be, they’re going to take bigger risks in life. They can walk through life without fear.

“That, to me, is the most important thing,” Harris said. “If you think, ‘I’m afraid I will lose everything if I do that,’ you will never live to your fullest potential.”

To others looking to become more self-reliant, Harris’s advice is to gain knowledge and experience in “fun and normal circumstances to see if you can do it—and most people can,” she said. “You need salt for curing, a water source, knowledge to build a fire, and some basic cooking tools,” she said. “That’s a skillet, seasoning, twine, a good knife, and a cooking board. You can feed the world with that.” Her long-term goal is “just to reach as many people as I can,” she said, “and to encourage them in their walks of life.”

Living a Life of Joy

Harris wakes up each day with more tasks on the agenda than she can possibly get done. But by praying every morning, she tries to follow the path that God sets before her.

Over the years, she’s realized that “sometimes you have to do the big stuff and let everything else go,” she said. She keeps a list of her priorities in order: “God, husband, kids, home, extended family, church and community, emails, notes, business.” Every day she considers what needs her attention, and her list helps keep what’s most important at the forefront. Since she keeps family first, even their interruptions come before her other tasks, and she raised her kids to know that they can go to her at any time with anything to say.

She feels grounded by how well they have turned out: “They’re seeking God, they’re doing things together, they’re movers and shakers,” she said. “I think walking in joy every day, choosing to walk in joy, helps that. [It] helps your children to want what you have.

“If I start feeling anxious or short-tempered, then I know I’m not going in the right direction, I’m not doing what I should be doing because I should be able to do it in peace,” she said. “My calm is a peace inside. If I can’t laugh, then something’s wrong.” For Harris, life is a journey that she chooses to walk in joy and in harmony with the world she shares.

From January Issue, Volume 3