As a teenager, I had little time for classical music. Opera just about made my hair stand on end. Choirs would send me running for the door. Orchestral music, in general, had been written for fuddy-duddies or nerds, I thought. It might not be too much of a generalization to say that most teenagers are drawn more toward hot dogs, fizzy drinks, and loud music than fine wine, nicely aged cheddar, and a prelude, but I have often wondered why. Is it perhaps simply a matter of waiting until we have matured and developed a more sophisticated sense of taste?

However, a dear friend of mine, an older composer, assured me it was otherwise. “One has to have suffered the slings and arrows of life, got some bangs and bruises, suffered unrequited love, lost a loved one or suffered a few failures, to appreciate the beauty of the finer arts,” he assured me. “Fine arts are a salve for the wounds, chicken soup for the soul. Teenagers have little use for salves. They are, after all, immortal, are they not?”

I couldn’t disagree. Indeed, in moments of doubt, I have clung to the arts, keeping my attention on the higher expressions of life and humanity, if only to maintain hope.

This last year has been difficult for us all, no doubt. Few have escaped unscathed, and yet somehow we seem to have made it through the slings and arrows. There seems to be light at the end of the tunnel, but I wonder how people have managed.

During my most difficult days, I had quite a few good friends I could turn to. Most of them died a hundred years ago or more, but their music is still very much with us. One of them left us just forty years ago, and yet his contribution stands with the greats of all time. His name is Samuel Osmond Barber II.

Barber was born in Pennsylvania in 1910. Music critic Donal Henahan said of him, “Probably no other American composer has ever enjoyed such early, such persistent and such long-lasting acclaim,” and yet, while I can almost guarantee you will at least have heard one of his compositions somewhere, few know his name.

You may have heard this particular piece in several movies, from David Lynch’s “The Elephant Man” to Oliver Stone’s Oscar-winning “Platoon.” There is even an electronic dance music cover by the famed DJ Tiësto, which, though it veers drastically from the original, is actually pretty great!

The composition I am referring to comes from the second movement of Barber’s String Quartet, Opus 11, the iconic “Adagio for Strings.” It is a composition of such lilting and yet uneasy and suspenseful beauty that most composers would wait an entire lifetime for such a piece to come from their pen, and yet Barber was just 26 years old when he wrote it.

Author Alexander J. Morin said of the piece, “It was so full of passion and pathos that it seldom left a dry eye.” Right from its first gentle refrain, the mournful yet delicate strings begin an ascending melody that is passed like a holy grail from yearning cellos to violas and violins. With the end of each passage, the orchestra seems almost to pause for breath, or even to sigh, before continuing the melody’s upward progress, as if searching desperately for daylight through the clouds. Rising and falling in an arch-shaped progression, the ascent leads to a searing, breathtaking crescendo that could pierce the stoniest of hearts.

At a time when many composers had begun experimenting with curious scales and discordant musical arrangements—“modernism,” they called it—Barber shunned the trends, focusing on a lyrical use of classic tonal harmony that gave his work a singular and remarkable charm and beauty, catapulting it into the spotlight.

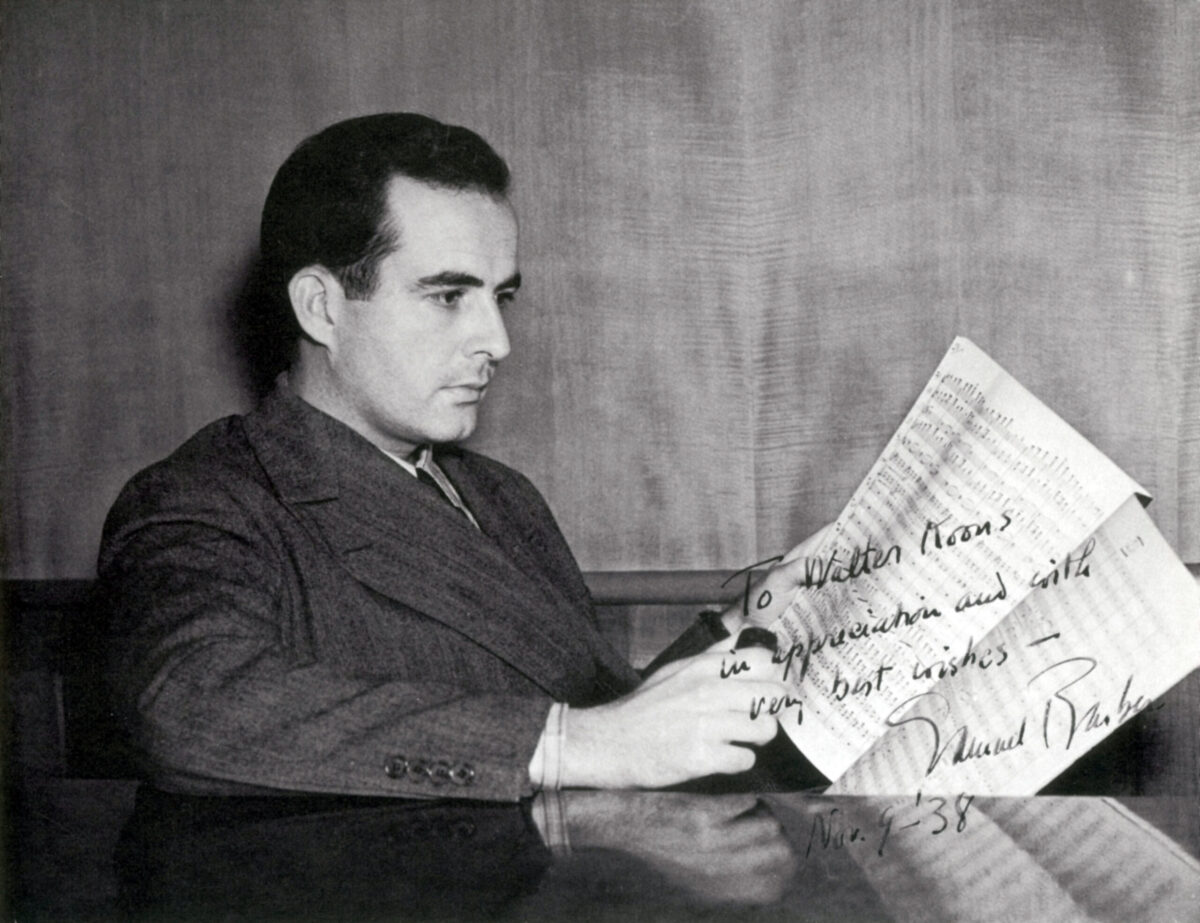

In 1938, Barber sent a copy of the orchestration for the “Adagio” to famed conductor Arturo Toscanini. Toscanini was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the 20th century, renowned for his ear for orchestral detail and his notoriously fierce perfectionism. When Toscanini returned the pages without comment, Barber was understandably quite upset. But Toscanini sent word that he had returned the pages simply because he had already memorized the entire opus! It seems the maestro was impressed.

In November of 1938, Toscanini conducted the piece for radio broadcast from Studio 8H at Rockefeller Center in New York. Apparently, Toscanini hadn’t had to look at the music until the day before the performance! The rest, as they say, is history.

Barber went on to win two Pulitzers, with many of his compositions being adopted as part of the canon of orchestral performance. He earned a permanent place in the concert repertory, with all of the renowned orchestras around the world performing his works.

The “Adagio for Strings” was later adapted for choir and titled “Agnus Dei,” meaning Lamb of God, referring to Christ in the liturgical text. It is beyond sublime and equals, if not surpasses, the heartrending orchestral version. While Barber’s mother was an accomplished pianist, his maternal aunt, Louise Homer, was a leading contralto at the Metropolitan Opera. She is known to have influenced his interest in voice, and some of Barber’s most beloved pieces are written for choir. While it seems natural that the “Adagio” would be adapted, the result is almost too beautiful to bear.

It is often difficult to reconcile the worst expressions of the human race when one witnesses the finest. After all, one need only read the news to fall into despair. However, the great writers, poets, painters and composers not only reflect how incredible we actually are as a species, but they continue to both salve our wounds and point the way to our higher ideals. Perhaps it is right that we pay attention to world events, but that is all the more reason to pay attention to the miraculous beauty that surrounds us, too. And so, dear reader, in this time of healing, after having suffered the slings and arrows of this past year, I heartily recommend you take solace in Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings.”

Pete McGrain is a professional writer/director/composer best known for the film “Ethos,” which stars Woody Harrelson. Currently living in Los Angeles, Pete hails from Dublin, Ireland, where he studied at Trinity College.