A “white Mulan?” That’s weird, they bluntly told her.

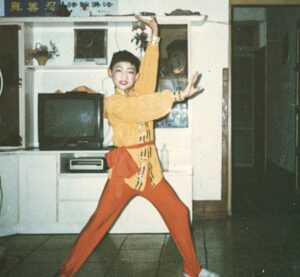

Katherine Parker, an award-winning dancer with Shen Yun Performing Arts, the world’s premier classical Chinese dance company, recalled the first time that she portrayed a historical figure in a dance. For a local competition, she wanted to tell the story of Hua Mulan, the courageous heroine of one of ancient China’s best-known legends. Despite her reservations, she decided to press on.

As the legend goes, Mulan disguises herself as a man to go to war in place of her elderly father—thereby saving his life. By imperial decree, one man from every family had to serve.

She fights for 12 years on the frontlines. The dance meant to capture her thrilling moments on the battlefield—but more than that, to tap into an internal struggle. The fast-paced battle music gives way to a slower melody, and the audience gets a glimpse of Mulan’s thoughts.

“Throughout the piece, Mulan is simultaneously waging an inner battle,” Katherine explained. “She longs to return home to her father, but she must remain where she is and fight in a bloody war. The irony of her predicament is that she wishes to take care of her father more than anything, but for his sake, she cannot return to him. I feel this dance highlights Mulan’s filial piety and selflessness.”

Katherine knew that capturing that emotional complexity was crucial to the success of her performance.

“I generally tend to hold back, and automatically close myself off a bit when standing in front of an audience. Often, I doubt myself,” she said. “And the moment I hesitate, the performance falls to pieces, because I am no longer in character—I am just being my old self.”

To prepare, she repeatedly listened to the music in her free time.

“I would sit there with my eyes closed and visualize Mulan’s story playing out in my mind, in sync with the music. I would imagine the battlefield, the war cries, and the hoof beats of galloping horses. When the softer, sadder music began, I would focus more on Mulan’s emotions and the heart-wrenching sorrow of being separated from her father.”

The dance was a success: She won gold.

The following year, her growth became apparent on a grander stage. At NTD’s 10th International Classical Chinese Dance Competition in 2023, she portrayed another great Chinese heroine, Lady Wang Zhaojun, who chose to marry the leader of a northern nomadic tribe to prevent war, leaving behind her beloved homeland and family in an act of selfless sacrifice. For her moving performance, Katherine took home a silver medal.

On the same stage that year, her older sister, Lillian, and younger brother, Adam, won silver and gold in their respective divisions.

The secret to their triple win? The siblings point to years of honing not only their craft but also their moral character—the true key, they say, to artistic excellence of the highest level and a core tenet of this millennia-old art form.

Based in upstate New York, Shen Yun was established with a mission to revive 5,000 years of true, traditional Chinese culture, a glorious heritage that was nearly destroyed under communist rule. The company’s eight troupes tour internationally each year, and its elite performers hail from around the world—from America, Europe, Asia, and Australia.

It’s a distinctly Chinese art form, but one that has resonated with people from all walks of life. Whether it be a daughter’s devotion to her father or a patriot’s sacrifice for country, the values portrayed are universal; its power to connect transcends boundaries.

“Dance is a language without words,” Lillian said.

Foundations of Family and Faith

A uniquely expressive art form, with roots tracing back to martial arts and Chinese opera and theater, classical Chinese dance has the power to depict an endless spectrum of stories and emotions. The Parker siblings were captivated by it from a young age.

Growing up in multicultural Toronto, Canada, their family made a tradition of seeing Shen Yun when it came to their city each year.

“We would all get dressed up, and we’d be bouncing in our seats, waiting for the show to start, so excited,” Katherine recalled. “When the curtain opens, it’s just magnificent. It blew our tiny little minds.”

Their parents, Andrew and Christine Parker, signed them up for classical Chinese dance classes when Lillian was 6, Katherine 4 1/2, and Adam 3.

“They had an interest in cultural dance, and they just loved it,” Andrew said.

Such early immersion in the arts was part of his and his wife’s vision to “have a traditional lifestyle for the children,” Andrew said.

“We wanted to fill them with as many wholesome and positive things that we could,” he said.

They sought out traditional values from different cultures, finding inspiration in the moral foundations of both Western and Chinese civilization, what “people in the past used to think of as virtuous, or good.”

“Honor, integrity, loyalty, honesty, good old-fashioned hard work, kindness—these were the things that we wanted to pass on to the children. These are what people traditionally refer to as the God-given values, or maybe in Chinese culture, they’d say the divinely bestowed values,” he said. “I believe [these values] are what actually make people feel whole and feel good on the inside, not necessarily the modern values that are promoted nowadays.”

An avid student of the classical art of storytelling, Andrew regaled them with tales, one of Adam’s most vivid childhood memories.

“Some parents might tell their kids stories to entertain them, but whenever [my dad] tells a story, there’s always a moral behind it,” Adam said.

The whole family enjoyed music, so Andrew would often set his story to a tune—such as one of the “Star Wars” soundtracks—describing the action of a scene as it unfolded to the score. (“He watched the movies so many times, he memorized all the scenes,” Lillian explained.)

Looking back, Lillian realized how that helped set an early foundation for her dancing career.

“We’re hearing the storytelling, and the moral of the story, but at the same time, connecting with the emotions in the music … how the music is bringing out the emotion. Now, whenever I listen to music, I’m automatically thinking of dance moves, or a story or a character starts forming,” Lillian said.

Like their parents, the Parker siblings practice the Chinese spiritual discipline of Falun Dafa. Based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, with an emphasis on refining moral character, the practice fostered a harmonious family life—and set the foundation for a sort of rectitude and grit that would continue to drive the siblings beyond childhood.

“It’s like the root—it shaped us a lot,” Lillian said.

At home, the siblings nurtured rich, creative lives, too. Aside from the occasional family movie night, their parents kept a screen-free house—no TV, no video games. As a result, the kids were naturally drawn to books, the arts, and other creative activities to fill their time.

“I’m grateful to our parents for that,” Katherine reflected. “A lot of kids are in their own box with this technology, and it can really suck you in. Staying separate from that, we could learn.”

They devoured books, from “The Lord of the Rings” and “The Chronicles of Narnia” to Nancy Drew and ”The Hardy Boys.” Lillian, an aspiring novelist, wrote stories of her own. They created their own clubs and crafted mailboxes out of cereal boxes to leave at each other’s doors.

Most memorably, they put on an annual Christmas show for a captive audience of parents, grandparents, and stuffed animals, complete with original dance choreography, music, lighting, costumes, tickets, a security guard (5-year-old Adam), and a rotating emcee. It was influenced, no doubt, by the format of a Shen Yun performance.

So while the Parkers had no expectations for their children to pursue Chinese dance professionally, it hardly came as a surprise when they did. When Lillian was 12, after watching the annual Shen Yun performance, there came an opportunity to audition for Fei Tian Academy of the Arts, which teaches classical Chinese dance, the primary art form of Shen Yun. She decided to try out, especially moved by how Shen Yun uses the art form to tell an important story on stage: the modern-day plight of her fellow Falun Dafa adherents in China amidst the brutal persecution of the faith by the ruling communist regime since 1999. Exposing the persecution is something that “no other performing arts companies are doing,” she said, “and that’s very meaningful. That’s not an opportunity you can find elsewhere.”

The family relocated to New York to support Lilian’s studies, and one by one, Katherine and Adam followed in their sister’s footsteps.

“[Lillian] auditioned at the school and got in, and then [Katherine] did too,” Adam said, so the next step was only natural. “I mean, I had to try out,” he said, smiling. “Everything was preparing me for that moment.”

Dancing in Chinese

Still, they were unprepared for other aspects, such as the rigors of classical dance training—with challenges understanding what their Chinese-speaking dance teachers were saying.

Learning the language was just the beginning; trickier was parsing the hidden layers of meaning beneath the surface, due to cultural differences in communication styles and etiquette.

“Westerners are very direct—what I say, that’s what I mean,” Lillian said. Chinese people, on the other hand, place value on self-restraint and thus “always hold something back.”

The differences spill over into the language of dance. She’s been told by dance teachers that her movements often look “very frank, very ‘Ba-bam! I’m here!’” she said. Classical Chinese dance, however, calls for a sort of restraint, a tension behind each move, a unique feeling built into the principles that underlie and define the art form. A hero character striking a pose facing the audience, for instance, would never hold his shoulders and hips square and stiff, but instead perhaps twist an opposite shoulder and hip toward one another, in a more dynamic stance. Or take the movement of bringing an arm up and over one’s head: Rather than straight and rigid, the movement would be rounded and pulled back at the edges, as if painting a rainbow with a brush, following the art form’s emphasis on roundness.

“Every part of your body [has] that feeling, … to the point where it’s a look in your eyes,” Lillian said. “That’s what draws in an audience.”

They often lean on each other for support: At weekly “Parker Council” meetings, they swap videos of their practice sessions and advice for improvement. They found that they not only think and feel similarly, but also hit similar roadblocks in dance. One sibling could thus help another translate confusing feedback from a teacher, as Katherine put it with a smile, “into Parker language.”

Universal Values

A crucial component of their training takes place outside the dance studio, in the classroom: Students at Fei Tian study, among other subjects, Chinese history, its rich repertoire of stories and legends, to understand the values that form the foundation of the culture—and inform every movement of the art form. The Parkers found the same universal virtues they’d grown up with in Western culture—faith, loyalty, integrity, kindness—but embedded at a deeper level.

“China’s had 5,000 years for those values to sink into the Chinese people’s hearts,” Adam said.

To be able to experience and take part in reviving such a rich heritage is “just so precious,” Katherine said. What struck her most was how firmly so many figures in Chinese history held to their moral convictions.

“They’re going to do the thing that they believe is right, no matter what the consequences are. It’s part of who they are, so they will give up everything for it—even their life. And it wasn’t just one or two people, but the society as a whole,” she said.

On stage, they channel these ancient figures—whether a palace maiden, an imperial scholar, or Mulan on the battlefield.

“One of the biggest changes for me as an artist was acquiring the ability to really get into character and feel whatever the character would be feeling,” Adam said. “There’s a saying we use in dance: ‘To move the audience, you have to first move yourself.’”

Imbuing every movement with genuine emotion, “the audience will actually be able to feel it, even if they’re really far away,” he said.

Being able to convey these values to the audience is key to capturing the essence of classical Chinese dance. Beyond the demanding technical skill required, to truly be a great dancer, “you have to be a good person,” Lillian said. “And then, you have to want to express or share those values through dance.”

Training in Chinese dance, like all the classical arts, inherently shapes dancers into better people, she pointed out, building self-discipline and the ability to persevere through physical and mental hardship. Maintaining the right mindset over the long run, always striving to be better without being discouraged, is one of the hardest parts, Lillian said.

A teacher once gave her a piece of advice that stuck with her: “Don’t be afraid of not being good. Just be afraid of not improving.” She resolved to focus on her potential to improve, on how much better she could get every day, “instead of being afraid of making mistakes.” She reminds herself: “Everything that’s hard is the root of something that will be great later—this is something that is going to make me into a better person or a better dancer. You see it as what it actually is—a tool to help you grow, even though it’s hard to go through.”

The siblings have also internalized lessons from the historical characters they’ve studied and portrayed. After they started their dance training, their father noticed profound changes in their character—most notably, that they had all grown more selfless.

“They’ve truly benefited from these traditional values and ancient virtues from Chinese culture,” Andrew said, “and because they’ve benefited from it so much, they truly have a sincere wish to share it with others. I think this is one of the main reasons why they can work so hard. … It requires a very noble spirit and a very pure heart; otherwise, you just can’t endure that much rigorous work.”

Lillian sees their art as having a higher purpose.

“Aristotle believed that one of the reasons people should learn music is to upgrade their moral values. By listening to good music, you’re learning how to enjoy something that is noble and something that is upright, and therefore, you are making yourself a better person,” she said.

Dance, she says, is the same.

“You should be giving out upright energy; the message you’re sending to the audience should be a positive, upright message,” she said.

She hopes audience members leave feeling uplifted and inspired to strive for goodness.

For Katherine, it makes everything worth it in the end.

“You know you’re doing something that’s just very special,” she said. “Not everybody gets the opportunity to be a part of something so remarkable.”

This article was originally published in American Essence, Vol. 4 Issue 1, Jan.-Feb. Edition.