Babies’ chew toys, Batmobiles, rocket engines—Art Thompson makes them all.

Thompson is a modern-day da Vinci, the rare sort of individual these days who is equally comfortable in the worlds of arts and technology, and more often than not bringing the two together. One of his earliest jobs involved running a sign shop—the owner handed it over to him a day after he’d started. He was still a teenager. Later, his art background came in handy at the aerospace company Northrop, where he made architectural models and was pulled into working on the B2 stealth bomber for over 10 years.

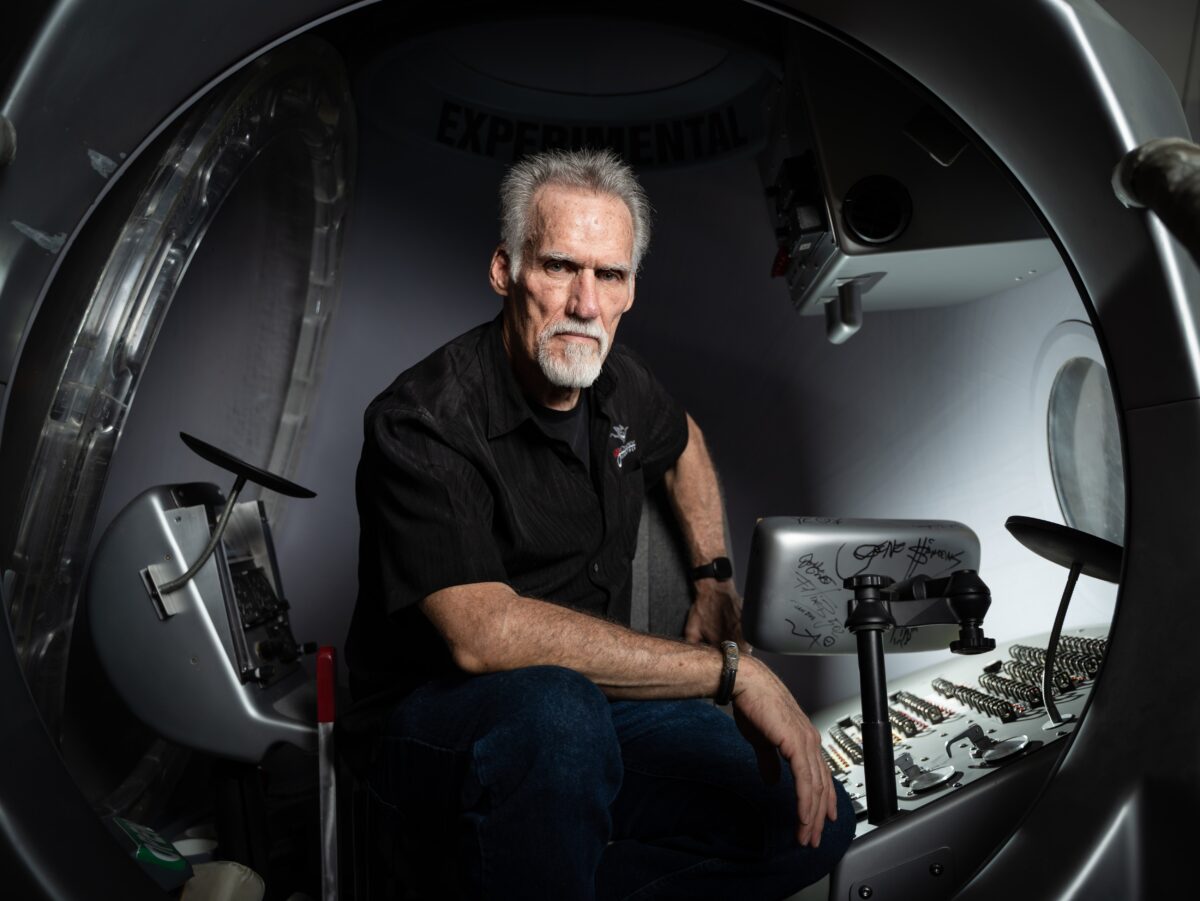

Thompson’s own companies, Sage Cheshire Aerospace and A2ZFX, share a workshop space in Lancaster, California, devoted to design, engineering, prototyping, fabrication, and testing.

Sage Cheshire regularly makes parts for government agencies or aerospace companies—from aircraft fairings and components to antennae for the U.S. Navy—much faster and cheaper than they could do themselves.

“We’re a super small organization and highly efficient,” Thompson said. “So while a company like Northrop or Lockheed or Boeing spends a lot of time in bureaucracy trying to figure out what they want to do, we’re already finished with the project. And so they realize that and use that to their advantage by contracting work.”

The company can take on larger projects, too, such as scanning and reverse-engineering an airplane that an aerospace company bought from a foreign provider, who wouldn’t give them the plans.

Thompson also has his own projects. Working with a space plane, he started to think about how he could develop the technology for a better defense system. Instead of using a hypersonic weapon against a hypersonic missile—the equivalent of launching a bullet to hit a bullet—he envisions launching a space plane at 250,000 or 350,000 feet in altitude, firing pulses of laser, which would have a better chance of hitting the target, since the speed of light is faster than the speed of a hypersonic missile. With its small footprint, the plane could also be used for reconnaissance and be transported easily anywhere around the world and launched from a regular runway, unlike a rocket.

While Sage Cheshire handles some serious business, A2ZFX focuses on product development and special effects—from the mundane to the spectacular. For example, the blister-like yellow bumps on sidewalks? Thompson’s team made the original version of these “truncated domes,” as they’re formally known. “And I cursed myself every time going over them with a shopping cart—along with millions of other people,” he said good-naturedly. A more dramatic, and flammable, example involved recreating a flying object zooming around in the air, to mimic the Human Torch for the promotion of a “Fantastic Four” movie.

Some of his projects not only have an undeniable flair for fun but also are marketing gold—like the Hum Rider, engineered to show off a marvelous solution to traffic jams. Envision a Jeep Grand Cherokee, with a wheelbase that widens and a body that elevates several feet above traffic, leaving stunned commuters below in the dust. Conceived to promote Verizon’s Hum dongle and smart app, the video made ripples through the internet, receiving a billion views.

The energy drink company Red Bull, with its marketing strategy embracing extreme sports and jaw-dropping stunts, was another client that was a natural fit.

When Red Bull was in its early stages of entering the U.S. market, it hired Thompson to make its eye-catching “can cars”—Mini Coopers outfitted with giant Red Bull cans on top, deployed with reps all over the country to offer samples of its product. Thompson built over 1,000 of these vehicles, although he jokes he had to build 3,000 cans to replace the ones that got destroyed. He said, “We would always tell [the drivers], ‘Don’t drive into the parking structure,’” which they invariably would.

Mission to the Edge of Space

In 2005, Thompson got a call from Felix Baumgartner, an Austrian friend whom he’d met at a Red Bull go-kart race in Austria. A daredevil and base jumper, Baumgartner was best known for his unpowered winged flight across the English Channel from 30,000-foot altitude in 2003 and jumping off the world’s tallest buildings, such as the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia.

He asked Thompson if he knew Joe Kittinger, who had jumped from a balloon at 102,800 feet in 1960 and reached a speed of 614 miles per hour, sustaining freefall for 4 minutes, 36 seconds. It was a record that stood unbroken.

Then he asked Thompson: If you were to break Kittinger’s record, how would you do it? Baumgartner wanted to know if it was possible to jump from space or the stratosphere and fall at supersonic speed.

“You know,” Thompson recalls telling him, “It’s 3:30 in the morning in Austria. Why don’t you go back to sleep, I’ll call you tomorrow and I’ll tell you some ideas.”

He ended up writing an 87-page proposal including how a pressurized capsule could be built, with redundant life support, spacesuits, and stratospheric balloons.

Thompson flew to Austria to present the idea to Dietrich Mateschitz, the late owner of Red Bull, who engaged Thompson as the technical project director for the Stratos project. But Thompson didn’t want it to just be a marketing stunt. It needed to be real science with a purpose.

Though Kittinger had made his jump over 50 years ago, the protocols around high-altitude freefall were few. Thompson saw a real-world opportunity. For him, it was about developing and researching how a U.S. Air Force or NASA pilot could safely exit a high-altitude craft, as well as medical systems to treat astronauts and pilots in case of ejection and rapid decompression.

“The beauty of it is, the government didn’t pay one dime for it,” he said. “I got an Austrian energy drink company to pay for all of the development. We then shared this knowledge with the government for free.”

“That’s the future of business, because the power of social media is that tool that can be used to fund future research,” he said.

Say you wanted to go to Mars, Thompson offered by way of example. “The government doesn’t want to pay for going to Mars. … But if you could go to a tennis shoe company and say your tennis shoes are going to be the first ones going to Mars, and it’s going to cost this much,” these companies, with their huge marketing budgets, could step in and fund research programs that the government isn’t willing to fund.

Doing the Impossible

During the Stratos project, another project turned up that Thompson couldn’t refuse. The Pima Air and Space Museum asked him: Would he build the world’s largest paper airplane?

When he was young, he would use newspaper and coat hangers and build giant paper airplanes. The largest he got was about 5 feet.

This time, the dimensions were only limited by the need to fit the plane onto a semi truck. Built entirely out of paper, it was 45.5 feet long, with a 24-foot wingspan, and required 20 gallons of wood glue to put it together.

As 300 schoolchildren watched, a Sikorsky S-58T helicopter took the plane up to 1,400 feet in the desert, and it was cut loose. It hit 98 miles per hour and flew just short of a mile. For Thompson, the main goal was achieved: to promote STEM education, and “help kids think outside of the box—that anything’s possible.”

“If I could have $1 for every person who told me the Red Bull Stratos was impossible, I’d be a millionaire,” Thompson said. There were physicists screaming at the end, ‘Don’t do it, his arms and legs will tear off.’”

Kittinger calmly responded, “Thank you for your concern, you may want to recheck your calculations.”

There was certainly a lot at stake, and the project team of fewer than 100 people was working hard to solve problems as they arose. Thompson said, “I was told ‘no’ every time I turned around and just found a way around the issue to make it a ‘yes.’ That is the lesson for the next generation. Never take ‘no’ as a final outcome.”

Then there was the unpredictable human factor.

After years of testing and development and only weeks before the first manned flight, Baumgartner got cold feet—he was at the airport in Los Angeles and called up Thompson, who rushed to go see him. Baumgartner, as it turned out, had developed severe claustrophobia inside his pressurized space suit. Human factors specialists Andy Walshe and psychologist Michael Gervais were brought in to help Baumgartner, pushing him into various uncomfortable situations and reminding him that he was a superhero and his pressurized suit was specifically designed for him.

Early on, it was decided that Kittinger, the one mission team adviser who understood firsthand what Baumgartner would experience, would communicate with him throughout his journey and talk him through the 47-point checklist before exiting the capsule.

The Space Capsule

Like Kittinger’s gondola traveling into space, the Stratos capsule was tethered to a helium balloon—but 10 times larger. At the size of 30 million cubic feet, it was the largest manned balloon ever flown. The ascent to an altitude of 127,852 feet took about two and a half hours.

Just as he prepared to jump off the ledge of the capsule, Baumgartner said, “I’m coming home now.”

“I know the whole world is watching and I wish the whole world could see what I see. Sometimes you have to go really high up to understand how small you really are.”

Thirty-four seconds after jumping, he hit Mach 1—just under 700 miles per hour. Fifty seconds after jumping, he reached March 1.25, a record speed of 843.6 miles per hour for a freefall. For 30 seconds, Baumgartner was supersonic.

He also set two other world records: the highest balloon flight (superseded by Alan Eustace in 2014) and the highest unassisted freefall. This Red Bull Stratos record is still a standing record, as Eustace’s jump was assisted with the use of a drogue parachute.

It was just 65 years before, to the day, that Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier piloting the Bell X-1 Glamorous Glennis.

Back on Earth, about 9.5 million concurrent viewers were transfixed watching the feat, as 3.1 million tweets pinged across the globe.

In all, it would be viewed by 3 billion people.

It was an unmitigated success for Red Bull, a marketing coup—delivering a big uptick in sales, by 7 percent to $1.6 billion in the United States, and by 13 percent to $5.2 billion globally.

Igniting people’s imagination was certainly one part of the formula, Thompson said. But he also brought to the table a more intangible ability: an ability to connect with and understand people from different backgrounds—scientific, medical, military, aerospace, and yes, even daredevil mindsets.

The Flight Test Museum and the Future

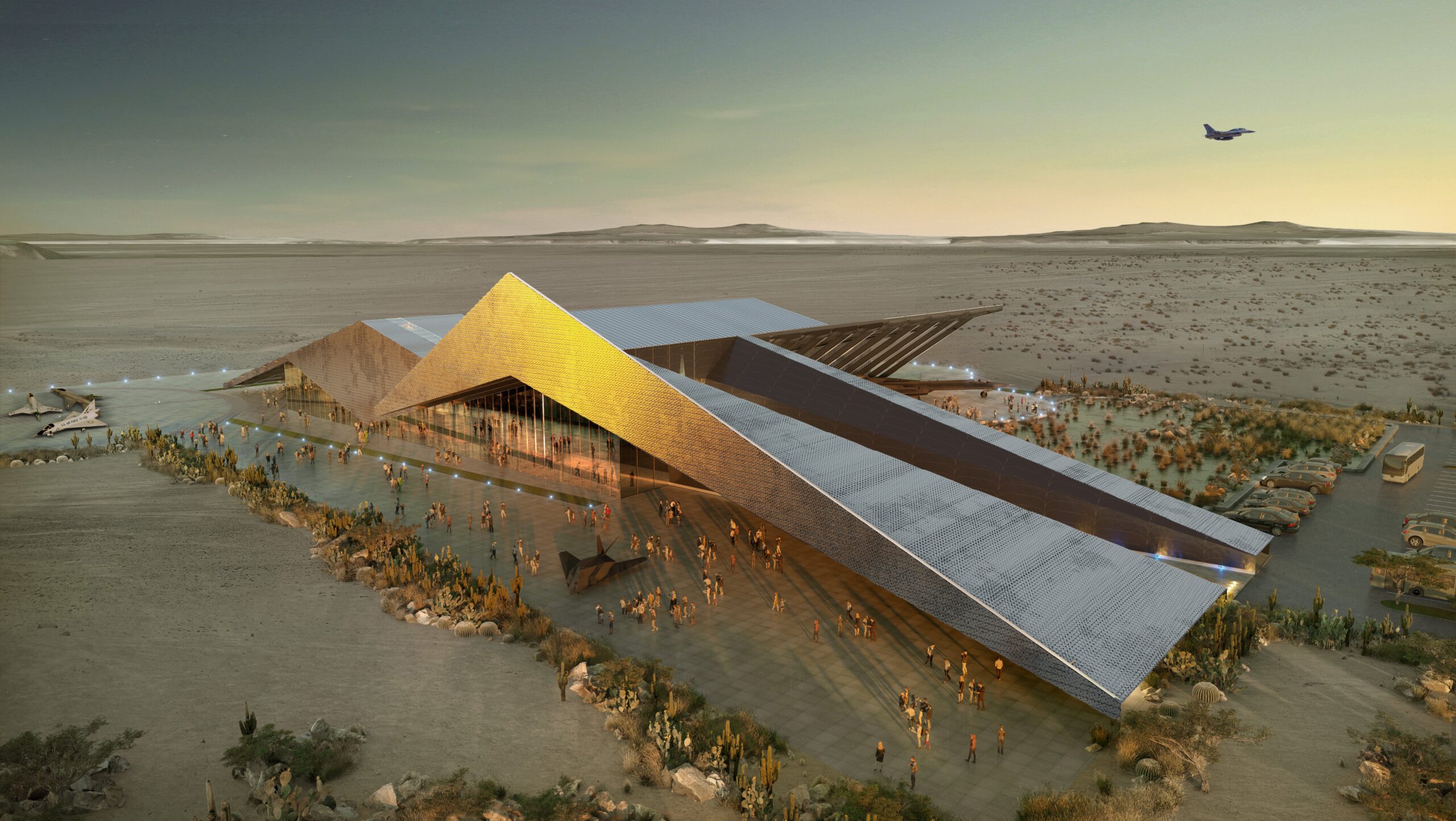

Stratos also made Thompson proud, partly because many kids told him it inspired them to get into engineering. As chair of the Flight Test Museum Foundation, he sees a unique opportunity.

California’s Antelope Valley, also known as Aerospace Valley, is home to many aviation firsts due to the presence of Edwards Air Force Base, the United States Air Force (USAF) Plant 42, and NASA’s Neil A. Armstrong Flight Research Center, as well as companies such as Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Virgin Galactic, and Scaled Composites.

“Some of the most brilliant minds in the world are located [here],” Thompson noted.

He is now overseeing the move of the museum, currently on-base, to a new home—75,000 square feet of space just outside of the base. It’ll house the museum’s rare aircraft, but it will also be a STEM education center, as well as “neutral ground” for industry players, government, and schools to come together to discuss the future and inspire the next generation to want to be part of something greater.

What concerns him is the phenomenon of students being “plugged into the Internet permanently” and being “spoon-fed” set answers like “a stone wheel is the best thing on a car.”

People want the answer quickly, Thompson said, but they don’t always know why they’re getting it. “We lose some of the creative aspects of invention and inspiration—because they settle for that answer.”

Thompson’s parents, both science teachers, made it a point to expose him to as many interesting things as possible. “One of my best Christmas presents when I was a kid was when my parents got me a stack of lumber with a saw and hammer and nails. I was five or six years old in the backyard and started building pirate ships and forts.”

His inquisitive nature even became somewhat of a liability for his family. “One of the fears was, if they gave me something that I was going to take apart, and if I understood it really well, often, I didn’t bother putting it back together because—why?—I already knew how it worked.”

When he was 13, he bought his first car, an old Karmann Ghia, for $500. He rebuilt the engine and redid the wiring harness—and drove it around without a license.

“Physics is so fascinating, because you see it in everything. And I remember as a kid, when math became a physical shape, all of a sudden, my mind exploded—because math formulas, you know, create not only two-dimensional shapes, but three-dimensional shapes.”

“If you can expose [children] to all the fascinating things in the world, at a really early age, that develops your synapses. All of that activity is making all those neural connections and mapping that make you want to do more and be more.”

It’s why he’s so passionate about the Flight Test Museum. “This becomes a world now that exposes people to what’s possible,” he said. “This is engineering in motion. It’s physics in motion.”

From February Issue, Volume 3