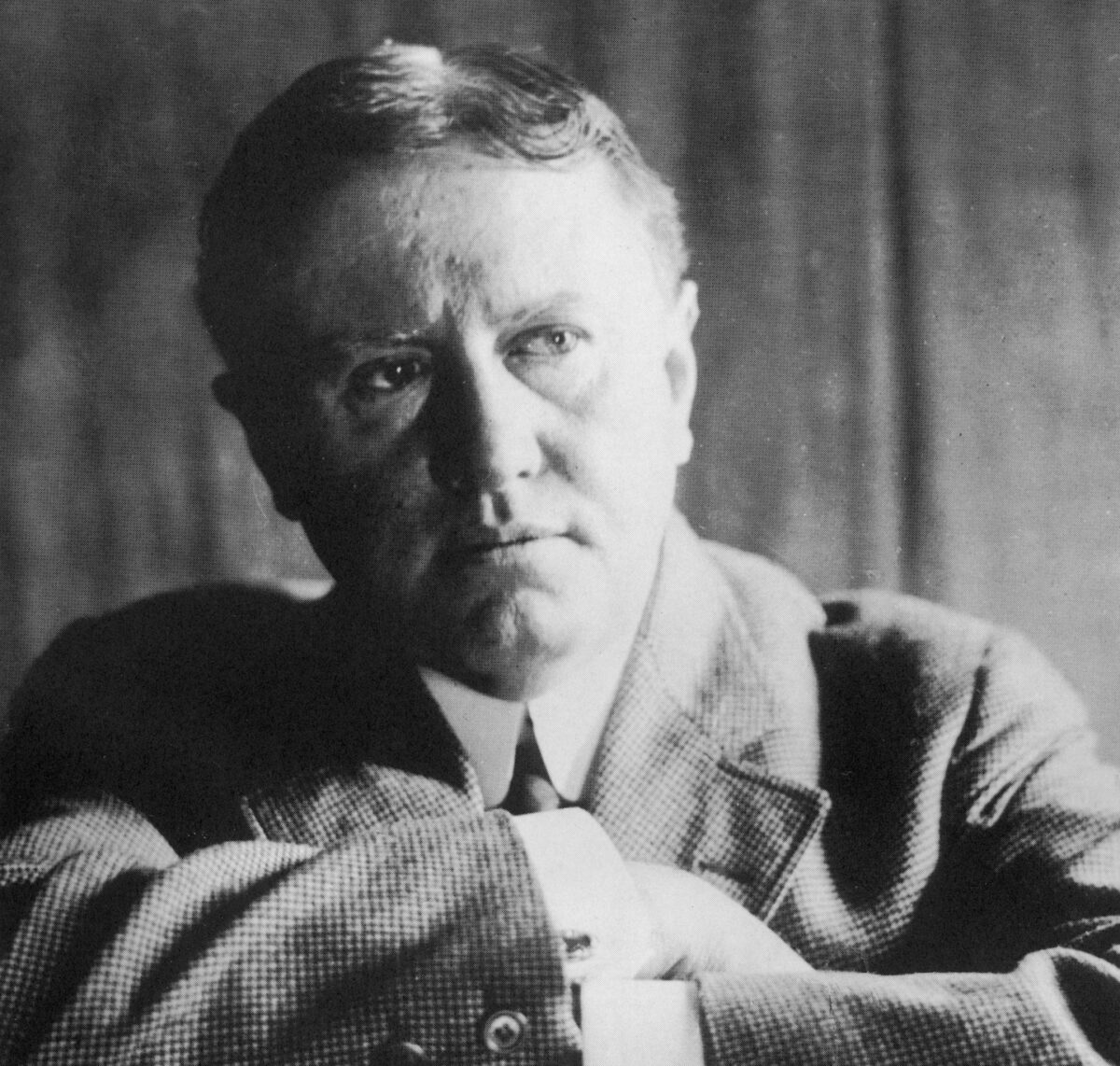

O. Henry is remembered by millions as America’s unparalleled maven of the short story. His stories were pithy, comprehensible, and moving, and there were hundreds of them. A brilliant force of nature, he could produce a pearl of a story in a single night and hardly ever corrected his work from the initial handwritten manuscript. If there ever was someone who seemed to possess an innate talent for putting into words the dreams, desires, and motivations of ordinary people, it was him.

But behind the pseudonym, there was a real man who once received reconciliation and a second chance and never looked back. He’s a sterling example of one who corrected and reinvented himself, who, when at a point in life of utmost crisis, took up their mat and walked.

A Man of Many Yarns

Born on a plantation on Sept. 11, 1862 at Greensboro, North Carolina, William Sidney Porter was raised by his grandmother. He left school at age 15 to work in his uncle’s drugstore, obtained a pharmacist’s license by age 18.

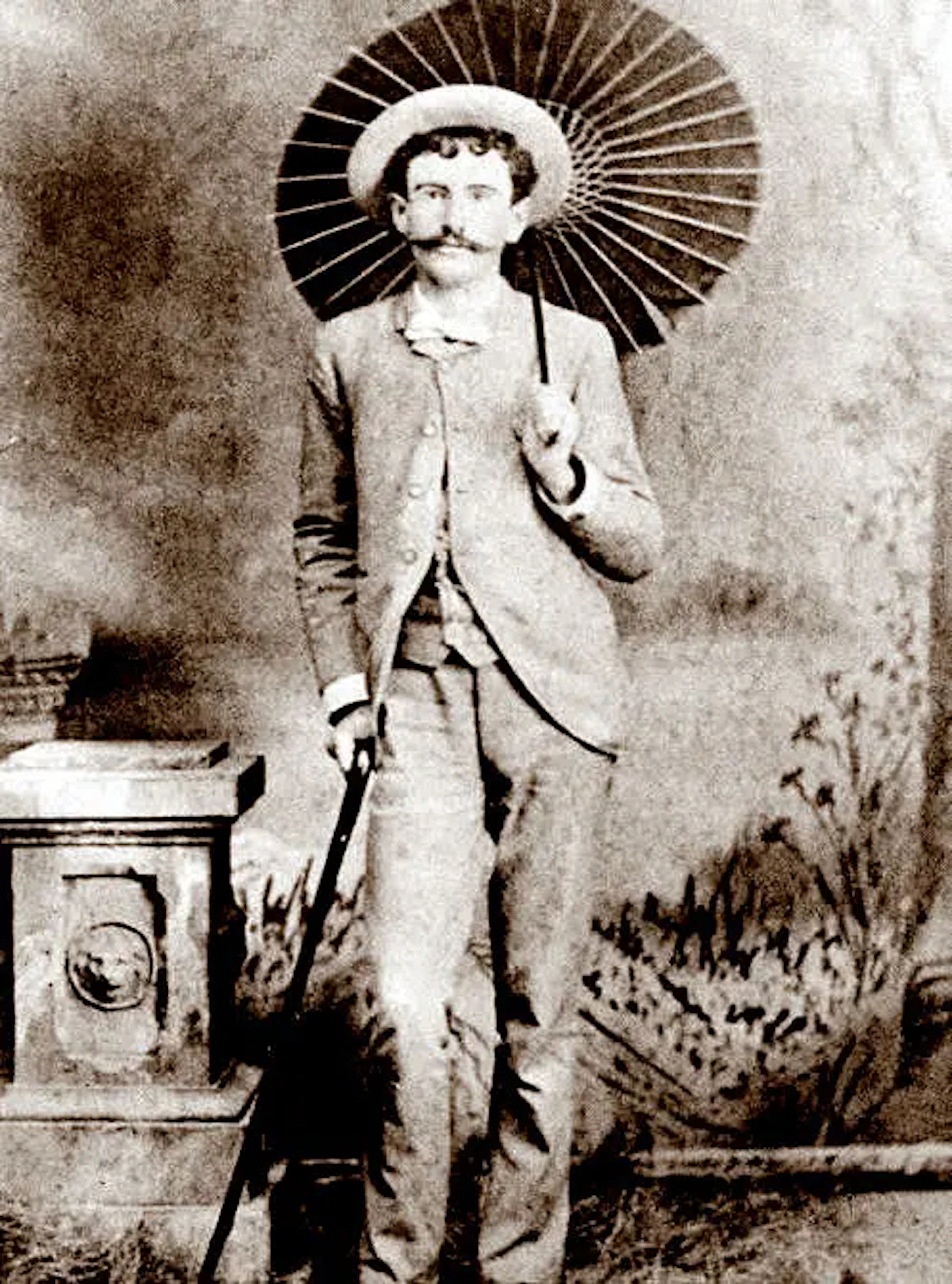

At age 20, he drifted to the rapidly industrializing West and, after settling in Texas, held a series of jobs, including working on a friend’s ranch, bookkeeping in a real estate office, and in a pharmacy. There are an epic number of stories floating around about Porter’s whereabouts and travels at that time and a fair share of them are most likely apocryphal. Indeed, from brazen cattle thief to miner and cowboy, to weary traveler and wandering tintype artist, the tales and legends attached to him are many.

“A lot of yarns,” he was once quoted in the Houston Daily Post as saying, “have been printed about me and none of them is true.”

What is known is that Porter moved to Austin in 1884, population of over 11,000, and worked a variety of odd jobs before finding work as a draftsman with the General Land Office.

Subsequently, he married Athol Estes Roach and found employment as a teller in a bank in Austin, where he was said to be kindly regarded by his customers and co-workers. Around that time, he became a columnist for a Houston newspaper and ran a weekly newspaper in Austin called The Rolling Stone, a comic and humor journal. He whittled away his free nights writing stories.

Life ostensibly seemed to only be getting better after the couple welcomed a son into the world. But then a string of ill-fated events changed the course of his life—and the trajectory of American letters.

Troubled Times

The couple’s infant son died in 1888, and Athol became tubercular. In 1894, a suspicious deficit had been discovered at the First National Bank where he had worked. He removed himself from his position and two years later he was indicted on four counts. Not willing to cope with the humiliation of a trial or its potential repercussions, he fled to New Orleans before eventually departing the United States. Porter ended up in Honduras, in July 1896, where he lived a harsh, difficult existence. (He also began writing “Cabbages and Kings” while in Honduras, notable for the introduction of the term “banana republic.”)

Informed that his wife was gravely ill, Porter returned to the United States about six months later. She died of tuberculosis shortly after. He was tried and convicted (some say unfairly and without legitimate evidence) for embezzling $854.08. He offered no defense for the misappropriation of funds, remaining silent at his trial, and the fact that he had run away was perhaps a sizeable factor in his conviction. He was sentenced in February of 1898 to five years’ imprisonment in a federal penitentiary in Ohio, entering as a shattered man, pushed to “the limit of endurance,” as he wrote to his mother-in-law. He had lost his son, his wife, his good standing, and his freedom, in addition to now also losing contact with his 8-year-old daughter, Margaret.

Embracing a New Path

But Porter dug deep within and he discovered a way to overcome his feelings of shame and affliction, accepting his sentence as an invitation to change. He made crooked ways straight, transformed himself into a new creation, and would ultimately become world famous for his talent.

Porter was a model prisoner: he worked long, overnight hours as the prison drug clerk and was secretary to the prison steward. He drew from his life and prison experiences, and, from a heart-piercing place of fresh insight, he learned from them. He befriended fellow inmates and based some of the characters and plots of his stories on their true-to-life accounts.

It would not be too much of a stretch to say that Porter rejoiced in the inward journey of writing and found some degree of refuge and repentance in it. One can only speculate how redemptive it must have felt to him when, as his new alter ego O. Henry, he sold his first story “Whistling Dick’s Christmas Stocking” to the national magazine McClure’s Magazine, in December of 1899.

Porter was blessed with an early release, serving only three years and three months out of his five-year sentence. He had sold about a dozen stories and earned a few hundred dollars from them, which was enough money for him to eventually travel east to New York City after he was freed on July 24, 1901. There, Porter earnestly committed himself to writing; drawing from a seemingly endless fount of lucid and compelling ideas, he mastered the short story form.

He never returned to Austin, and he never again used his real name. Some have proposed that his pseudonym was an abridged adaptation of the name of the French pharmacist Etienne Ossian Henry. The most commonly accepted explanation and origin story of the pseudonym O. Henry, however, is that Porter borrowed the name from a guard at the Ohio Penitentiary named Orrin Henry, who, depending of which account you decide on, was either Porter’s “favorite jailer” or no longer working at the time that Porter was incarcerated, but whose name was still available in the prison records.

A Sterling Second Act

In 1903, the Sunday supplement of the New York Herald started to publish his weekly stories of city life, and the response was overwhelming. O. Henry developed his own, one-of-its-kind style, a plain, frank approach to weaving a yarn, which, in time, made him one of the most read and circulated authors of his time. His well-crafted, deftly packaged writings are crammed with careful details and unforgettable characters—shopgirls, opportunists, neighbors, cops, landlords, ministers, artists, and waitresses, to name but a few—as well as the vivid juxtaposition of irony, intimacy, humor, and pathos. Precious for their colorful colloquialisms, surprise, laughter, excitement, and, occasionally, tears, O. Henry’s works withstand the test of time as some of the best turn-of-the-century vestiges of tongue and technique.

Supernaturally prolific, he penned, by some estimates, more than 600 short stories, including one of the most endearing Christmas stories ever written, “The Gift of the Magi,” and “The Last Leaf,” a thought-provoking reflection on the inherent symbiosis of death and life, told through metaphors of old ivy leaves and the regenerative pursuit of art.

The author known as O. Henry died June 5, 1910, in New York City, the conclusion of a remarkably successful and unique journey. Outside of the smartness and aptitude of words, William Sidney Porter profoundly exemplified the truism that, indeed, there are second acts in American lives, and that America gives second chances, and is especially generous to those who accept them with care.

From May Issue, Volume V