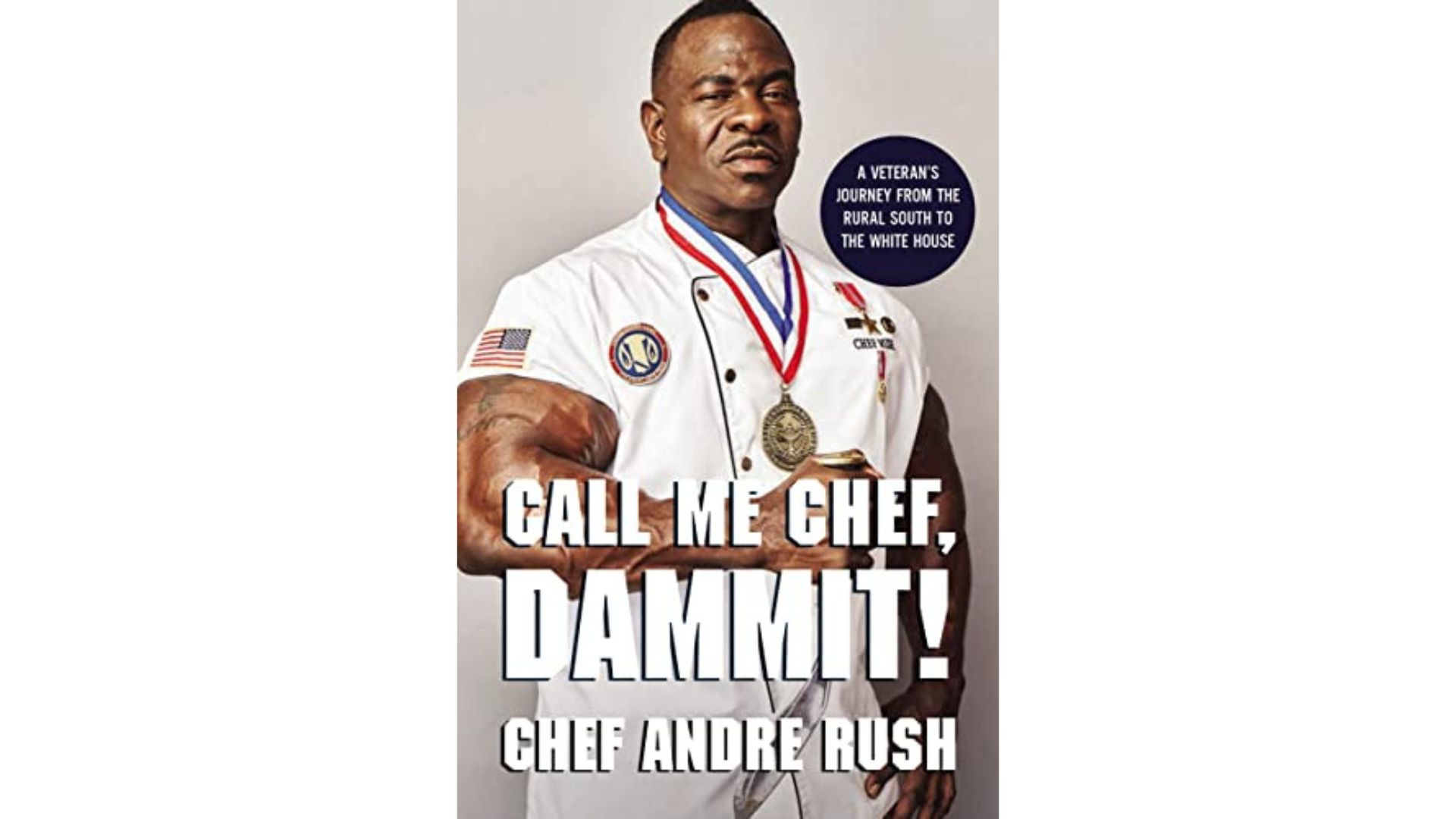

Standing at 5 feet, 10 inches and some 270 pounds with his famous 24-inch biceps, chef Andre Rush is used to drawing looks. But these days, they’re usually from excited 10-year-olds wanting a hug and photo with their “superhero,” he says.

Rush, a retired U.S. Army Master Sergeant, was a White House chef through four administrations, cooking during the Clinton, Bush, Obama, and Trump years. He now hosts the Gordon Ramsay-produced show “Kitchen Commando” to kick struggling Washington, D.C., restaurants back into gear.

Armed with heart and hospitality, Rush uses cooking to create community and raise awareness about mental health, especially for fellow veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), preaching love and service everywhere he goes. He’s proud that his message reaches young people—because the future generations need it, Rush says.

“There may be one little nugget in there who’s going to be Chef Rush times a thousand, and he or she is going to … find someone else to keep pushing it along,” Rush said.

An Unexpected Path

Cooking was never meant to be a career, said Rush. Growing up poor in Mississippi, cooking was caring and love in action.

One of Rush’s brothers was a Marine, the other was a Navy officer, one of his sisters was an educator who helped the blind, and his mother “cooked for everyone in Mississippi,” feeding all who needed it. Their father led the siblings—five girls and three boys including Rush—to pick food on local farms by hand, to embed fortitude and hard work in their characters. It taught him always to be the hardest worker in the room. It impressed upon him the value of service.

So Rush, who said he had earned an art scholarship, a track scholarship, a football scholarship, and Olympics prospects, decided to join the military himself. He soon joined the food service team only to learn it was nothing like what he thought cooking was about. “It’s mass feeding,” Rush explained. “Feed and go.”

But less than a year into his military career, Rush said a Sergeant Major came up to him out of the blue, told him about a culinary competition, and asked him to train for it.

“I didn’t even know what ‘culinary’ meant,” Rush said. He went down to train at the United States Army Culinary Arts Team annual competition in Fort Lee, Virginia, and saw that the hobby he grew up with, cooking alongside his mom, was a serious culture in and of itself. Sugar pulling, ice carving, pastry creation—it ignited the artistic side of Rush. “I just became infatuated with cooking,” he said. In the pre-internet era, he bought books he couldn’t understand to try to learn techniques he’d never heard of, and he used those competitions as his training ground. He went on to win 150 medals and trophies with the United States Army Culinary Arts Team.

A few years into food service, a call came from someone Rush once helped, asking if he wanted to go to Washington. It took him by surprise—even more so when he was told it was to cook at the Pentagon. There, and later when he cooked part-time at the White House, Rush learned much about diplomacy.

“They take food very personal, … it’s one of the main duties,” Rush said. “Food is morale. … Food can save lives and end lives, start wars and end wars.”

Salvation in Service

Salvation in Service

Rush is a combat veteran who stayed enlisted in the Army during his cooking career. On September 11, 2001, he was inside the Pentagon when the plane hit; it motivated him to return to combat duty and led to tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. He retired from active duty in 2016, and he continued to cook, consult, and prepare major events at the White House—while learning to cope with the acquired trauma.

Rush was in a Wounded Warrior unit, realizing that being surrounded by low energy was dragging him down, too. He decided to go to the gym instead, and, by chance, another veteran from the United Service Organizations (USO) next door decided to join him. “He was a kind of heavyset guy, and in two weeks, his body had changed,” Rush said. It stunned the others around him, and that workout team grew to 5, then 10, then 20.

Rush realized that working out to relieve stress was all well and good, but stress management had to be incorporated into one’s daily life to actually stick. He was cooking for himself at home when it dawned on him: What could be more vital than eating?

“I remembered my mother, I remembered everything that she taught me, and how I felt with it, so I held onto it and I decided to bring it over to the USO,” Rush said. He organized cooking classes for the group, and his own experience with cooking primed him to help others see it the same way. He would ask, “What’s your fondest memory of food?” Maybe their mother or grandmother used to make a favorite dish for them.

Cooking was supposed to be a vehicle for caring and connection, and so Rush grew the classes to include their spouses and children, pulling the veterans out of their isolation. He remembers a man breaking down into tears, apologies, and gratitude when he realized how much care and effort went into preparing a meal—what his wife had been doing for him every single day. A colonel was inspired to start a food truck for mental wellness after participating.

Rush shot to fame in 2018 when, while cooking at the White House’s Iftar celebration, a breaking of the Ramadan fast, a reporter’s photo of Rush and his 24-inch biceps went viral on Twitter.

He used his newfound platform to speak out about mental health and what veterans face, with initiatives like Mission 22, doing 2,222 push-ups every day to raise awareness about the fact that an average of 22 veterans take their own lives in America every day.

“We’re always going to struggle, it’s always going to be there. There’s not a perfect world of perfect people out there, it doesn’t happen that way,” Rush said. “What’s not OK is to not get support, because it’s not only about you, it’s about everything else that you do, everybody that you meet, and it’s also about future generations.”

“I have to break it down for people who think that ‘they’ll be better off without me.’ That’s an absolute lie. You know what, if that’s the case, dedicate your whole entire life that you were going to give up to doing something for everybody else. It’s that simple.” And Rush helps them do it—he takes his fellow brothers in arms to cook for underprivileged kids, people who look at these veterans who think they have no worth like they’re superheroes, too. “If it’s going to save [a] life, it’s going to help someone, then I’m going to do it.”

“It’s humbling to see that you can change someone in so many different ways from just food alone,” Rush said.

Food and Fitness With Chef Rush

You are what you eat—it’s a cliche, but it’s true, says Rush. “What you put in your body is what you’re going to give your body, and don’t say I’ll do it later—you have to do it right now, every day.”

Rush is an endurance trainer, but a core part of fitness is knowledge, he says, and that means understanding how to listen to your body and what it tells you it needs, because every ideal diet and regimen is individual.

“The first thing I tell people is always get your blood work checked out, get your body checked out,” he said.

Then, think about your goal. “When I say goal, I mean life goal, not your fitness goal. Life goal is ‘I want this for the rest of my life.’ They should be hand-in-hand.” Building a body is like building a country, Rush says, not a plywood house. To have a solid foundation, you have to think about your sleep cycle, your lifestyle, your mind, your environment, and everything in concert—it’s not just counting macros.

Rush starts his day with early morning meditation, followed by push-ups for his cause, and affirmations: “looking at myself in the mirror and telling me, ‘I can do anything, never give up, keep going,'” he says.

Southern Hospitality

“My mother showed me how to cook. It didn’t start with a recipe but with respect to others. … Whether she was serving her sons and daughters or a complete stranger, Mom always showed love and affection with the food she made. She instilled in me the same desire with the meals I would go on to create. It didn’t matter if they were presidents and kings and queens or homeless people. Hospitality means putting your heart into your work, every single time.” —Andre Rush in his 2022 memoir, “Call Me Chef, Dammit!”

RECIPE: Angry Chicken

From July Issue, Volume 3