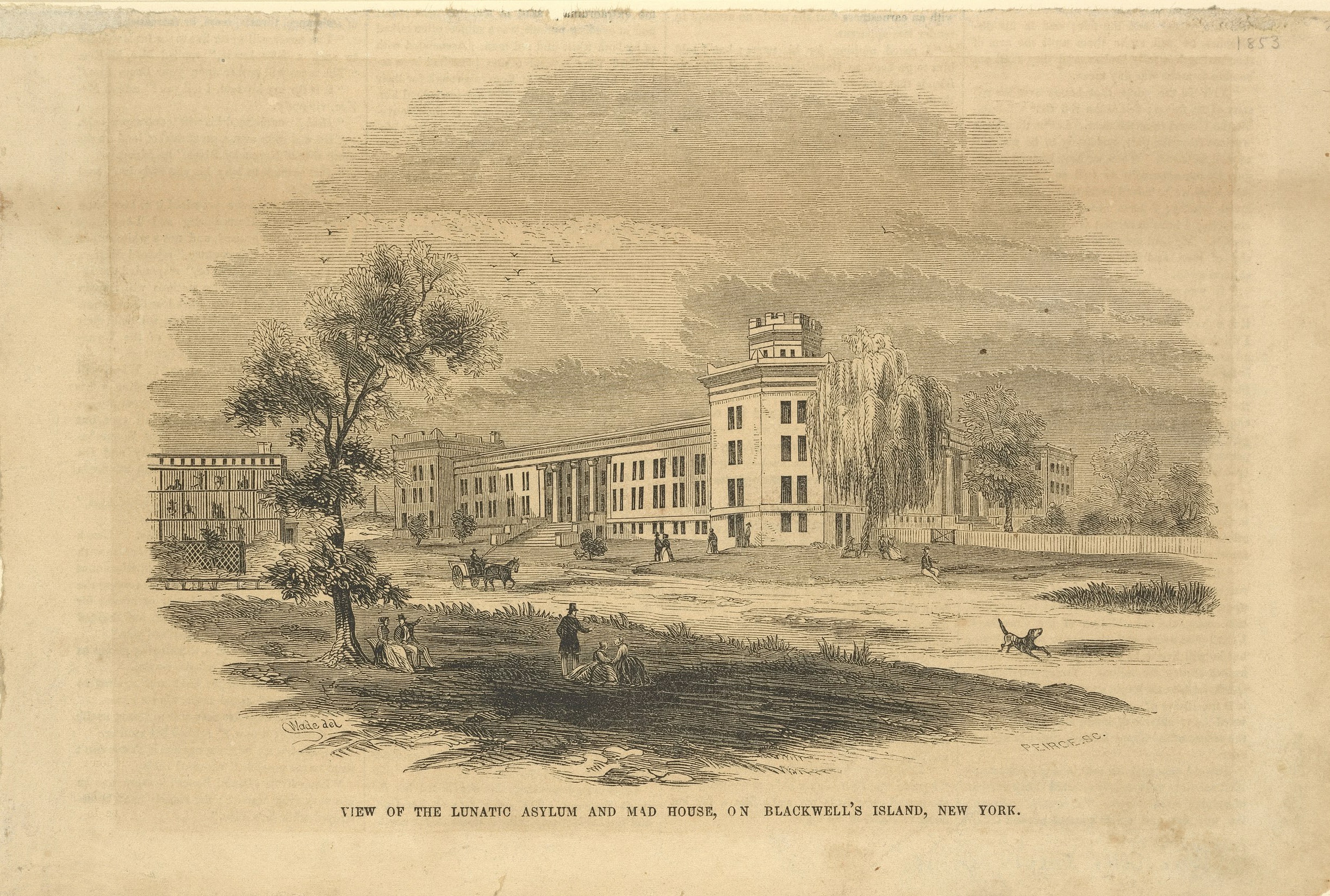

In 1887, Nellie Bly boarded the boat with the other patients bound for Blackwell’s Island, now known as Roosevelt Island. Their stay in the filthy cabin was mercifully short, and soon they crossed the East River and disembarked. After an ambulance ride, Bly and the others found themselves ushered into the stone buildings of the insane asylum. Unlike the others interned at the asylum, however, Bly came by choice. As an undercover reporter, she planned to witness the rumored abuses at the asylum firsthand and expose them.

“I had some faith in my own ability as an actress,” Bly later wrote. “Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island? I said I could and I would. And I did.”

The Reporter’s Beginnings

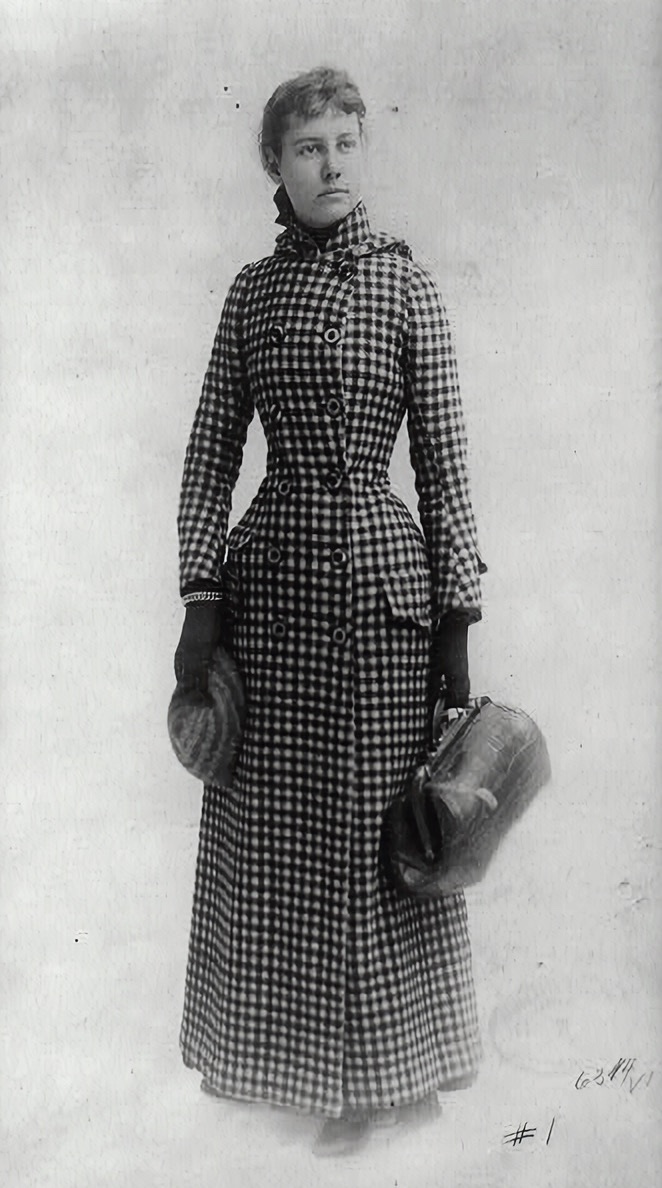

Nellie Bly was the pen name of Elizabeth Jane Cochran, born May 5, 1864, in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. When her father died young and his estate was split among his many children and second wife (Bly’s mother), the family fell on hard times. From a young age, Bly worked many jobs to help support her mother and family but struggled to find work that paid well.

In 1880, the family moved to Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, (the city was annexed by Pittsburgh in 1907). One day, Bly read an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch opposing women in the workplace. She wrote a letter to the editor offering an opposing view on the subject. Managing editor George Madden was impressed, and in the next edition of the paper, he asked the author of the letter to come forward.

“She isn’t much for style,” Madden said, “but what she has to say she says right out.”

Bly went to the Dispatch’s office and soon had a job and a pen name—Nellie Bly, after the popular song “Nelly Bly” by Stephen Foster. One of her first series for the Dispatch covered the conditions of poor working girls in Pittsburgh. At 21 years of age, she went to Mexico and wrote articles for the Dispatch until her criticism of the country’s censorship almost resulted in her arrest.

The majority of the articles the Dispatch assigned her, however, were simple, women’s interest pieces on entertainment, arts, or fashion. Bly wasn’t satisfied writing these pieces, so in 1887 she packed her bags and headed to New York.

A Secret Assignment

Bly tried to find a job at a New York newspaper for a few months to no avail, but she wasn’t about to return to Pittsburgh in defeat. Giving up wasn’t an option. “Indeed, I cannot say the thought ever presented itself to me, for I never in my life turned back from a course I had started upon,” she wrote.

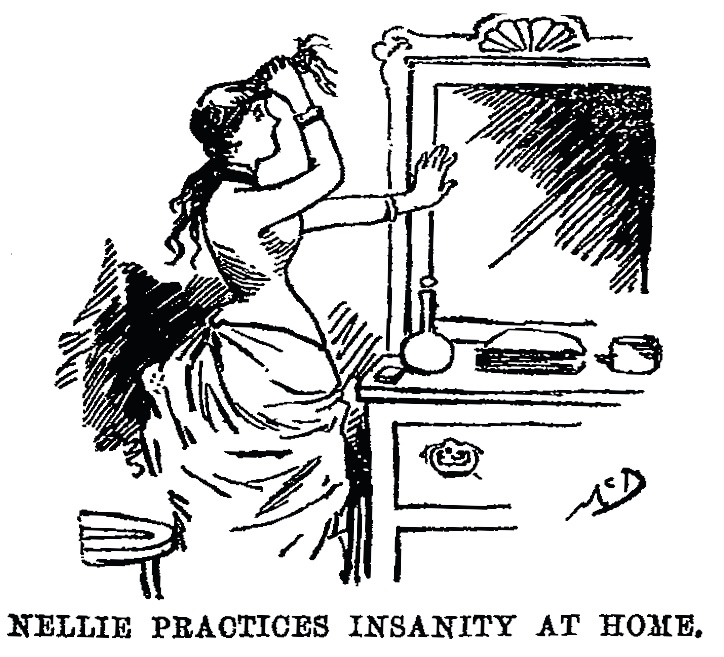

One night, Bly realized her purse was missing and with it the rest of her money. She went to the offices of The New York World and demanded to see the editor in chief. When Bly finally spoke to managing editor John Cockerill, she pitched the idea of riding in the steerage of a ship to Europe and back, reporting on the condition that passengers, primarily immigrants, endured. The World wasn’t interested in that idea, but Cockerill proposed a different idea instead. The 23-year-old Bly would get herself sent to Blackwell’s Island and experience the rumored abuses firsthand. Bly agreed to take the assignment.

“How will you get me out?” she asked.

“I do not know,” Cockerill replied. “Only get in.”

The Asylum on Blackwell’s Island

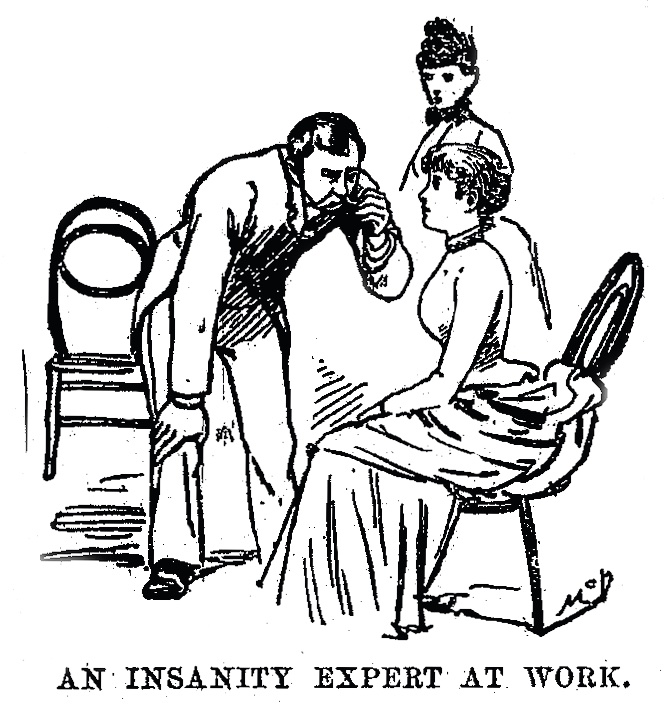

Bly rented a room at a boardinghouse called the Temporary Home for Females. Her theatrics there and at Bellevue Hospital soon earned her a place at the asylum. Once there, Bly quickly found the rumored abuses to be true. The food and overall conditions were horrendous. Many people at the asylum were wrongly interned, including some immigrants who didn’t get a chance to plead their cases because they couldn’t speak English.

The nurses and caretakers at the asylum treated all patients with contempt and cruelty. Bly gathered testimony from patients in addition to the experiences she herself endured. After arriving, she acted completely normal and explained to the doctors that she should be examined and let go. She quickly learned that her only way of escape would be when someone from the World came to get her.

“The insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island is a human rat-trap. It is easy to get in, but once there it is impossible to get out,” she wrote.

After 10 days in the asylum, an attorney from the New York World came and obtained her release. Bly found herself strangely conflicted upon her departure. “I had looked forward so eagerly to leaving that horrible place yet when my release came … there was a certain pain in leaving,” she wrote. “For ten days I had been one of them. Foolishly enough, it seemed intensely selfish to leave them to their sufferings.”

Bly wrote a series of articles exposing the asylum, which were then compiled into a book, “Ten Days in a Madhouse.” Later, she testified to a grand jury about her experiences. This led to an increase in funding for Blackwell’s and institutions like it to provide adequate care for patients. “I have one consolation for my work—on the strength of my story the committee of appropriation provides $1,000,000 more than was ever before given, for the benefit of the insane,” she wrote.

Honor and Truth

Bly’s career was never smooth sailing, but she continued to write the rest of her life. “Energy rightly applied and directed will accomplish anything,” she said.

Though plagued with writing filler pieces, she also wrote articles that exposed an employment agency, a company supposedly “selling” unwanted babies, another factory where girls worked in horrible conditions, a corrupt lobbyist, and more. She was in Europe when World War I broke out, so she served as a war correspondent, braving the front lines. All in all, Bly worked to report what she saw regardless of what subject she was assigned.

“Write up things as you find them, good or bad,” she said. “Give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time.”

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.