Michael Owens came from Irish stock. His family had escaped a potato famine and an oppressive British regime by immigrating to America, eventually settling in Wheeling, West Virginia. Here, there was mining work to be had. Being poor and one of seven children, it was important for 9-year-old Michael to contribute to the family income. Into the mines he went. The year was 1868.

One day, Michael was struck in the eye by a piece of coal, accidentally let loose by the overzealous swing of a fellow miner’s pick. The blow knocked the boy to the ground, and out cold. Mrs. Owens immediately decided that young Michael’s coal mining days were over. At age 10, then, he went to work as a “blower’s dog” in a local glass factory.

Ironically, coal remained a major part of the boy’s job. As a blower’s dog, Michael assisted the (adult) glassblower by keeping the furnace filled with the sooty stuff. The constant heat—not infrequently burning the boy—ensured that the soda ash, sand, and other ingredients mixed inside large pots and placed in the furnace could melt into blowable molten glass. The crew with whom Michael worked (perhaps half a dozen men and boys) produced roughly one glass bottle per minute.

Young Michael Owens worked 60-hour weeks. He was paid 30 cents a day. He went home each night covered in ash and coal dust. It’s a fair bet that his lungs were full of ash and dust, too.

Throughout his teens, Michael rarely if ever had the opportunity to benefit from a traditional school setting—but as the years passed, the lad gained a reputation as a diligent worker. He came to be meticulously trained in every aspect of the glass-making process. “Young or old,” Owens told an American Magazine reporter years later, “work doesn’t hurt anybody.”

At 20, Michael was still in the glass business, but now he was an employee of Edward Libbey’s Toledo Glass Factory. And Edward Libbey had money to invest in Michael Owens’s big idea.

Inventing a Bottle-Making Machine

It took Owens five years to produce it, then a few more to perfect it, but in the end (and after burning through half a million of Libbey’s investment dollars), he’d done it. Michael Owens had invented a working automated bottle-making machine.

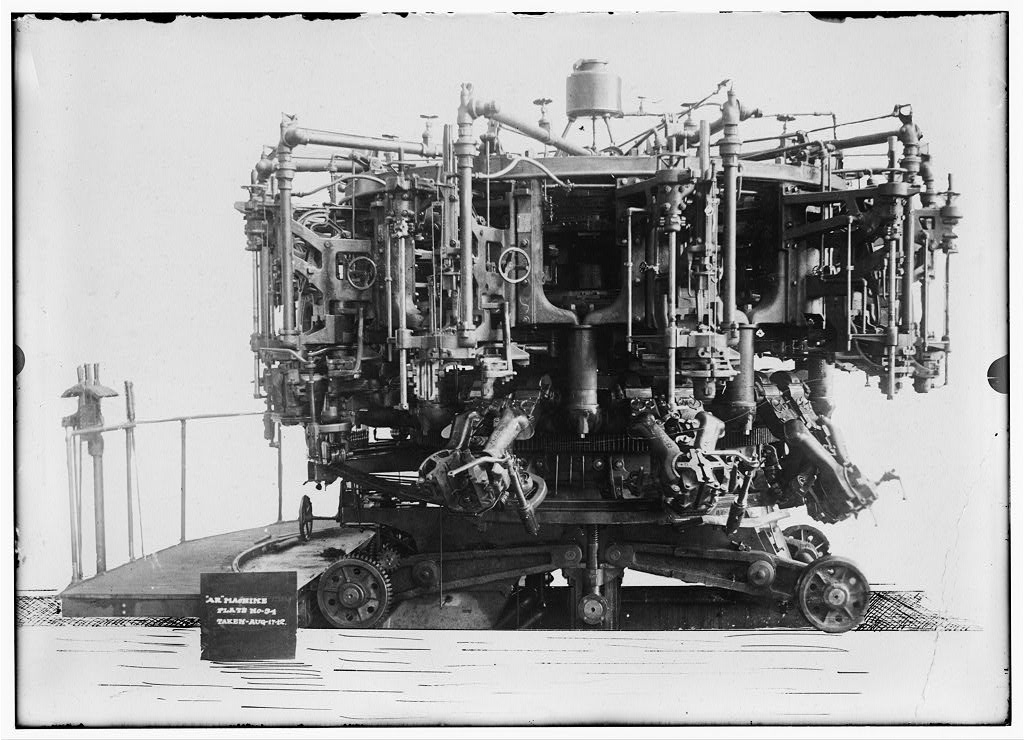

With six rotating arms (later more were added), each outfitted with a pump and a plunger that could suck up the molten glass and then push air into the mix, bottles were “blown” without a single human touch. The machine even cut the bottles and set them on a conveyor belt, which guided them into a furnace for final heating and cooling.

Even the first version of Owens’s machine was unquestionably more efficient than the most skilled human team of bottle makers. Thanks to his invention, one bottle per minute was now six bottles per minute. After making improvements, six turned to twelve. And not only could bottles be (many times more) efficiently produced, but they also could be more cheaply produced, since expensive, skilled blowers were no longer required. In addition, all bottles were now identical—sharing the same dimensions, the same weight, the same everything. Costs per bottle plummeted 94 percent.

Libbey and Owens quickly co-formed a new company in 1903, the Owens Bottle Machine Company, stocked with the new machines, which the two now licensed out to other companies. Within just a few years, Owens’s automated bottle-making machines could crank out almost 250 bottles per minute!

Founding Big Companies

Owens and Libbey went on to establish the Owens Bottle Company (1919) and, despite frequent criticism from doubters, collaborated over the years with another inventor, Irving Colburn, to perfect the production of distortion-free plate glass. The trio succeeded, and the Libbey-Owens Sheet Glass Company (1916) went on to make millions, too.

Now in his 60s, some wondered if the indefatigable Owens was considering retirement. “The real reason I keep on is because I like to [work], I want to work,” he is reported to have said. “It is the most interesting thing in the world, and it is the most constructive thing. I’ve enjoyed 52 years of it, and I hope to enjoy a good many more.” Owens went on to develop laminated glass for automobiles—he called it “safety glass”—which was much more crack- and shatter-proof than earlier varieties.

Toledo came to be known as “The Glass City,” Libbey was hailed as the father of the modern glass industry, and Mike Owens died a rich man at age 64 in 1923. In a tribute to the inventor published in The Toledo Times, Libbey described Owens as “self-educated,” possessed of “an unusual logical ability,” and “endowed with a keen sense of farsightedness and vision.” Libbey hailed him as “one of the greatest inventors this country has ever known”—one whose name “will stand out as a pronounced example of what can be accomplished by vision, faith, persistence, and confidence in one’s creative efforts.”

The Owens Bottle Company merged with the Illinois Glass Company to become the Owens-Illinois Glass Company—a Fortune 500 company to this day.

And 60 years after Owens’s passing, the bottle-making machine invented by an erstwhile West Virginia child laborer was hailed by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers as “the most significant advance in glass production in over 2,000 years.”

Dr. Jackson, who teaches Western, Islamic, American, Asian, and world histories at the university level, is also known on YouTube as “The Nomadic Professor.” You can follow his work, including entire online history courses featuring his signature on-location videos filmed the world over, at NomadicProfessor.com