John Perkins’s hands move with a passion that still fuels him at 91, as he tells his story of suffering and redemption. Like most black families in Mississippi in the 1930s, life was an all-consuming effort to survive. No one can remember Perkins’ exact birthday, but the significance of one early memory has become very clear.

John was living with his grandmother, a woman who had birthed 19 children of her own before taking in John and his five siblings. Pellagra, a vitamin B3 deficiency, had taken his mother’s life when she was still nursing 7-month-old John. Already-full beds grew fuller. John’s grandmother was supplementing their sharecropping income with bootlegging.

Mississippi had banned alcohol statewide in 1908, a decade before the 18th Amendment to the Constitution prohibited it throughout the nation. Then, Mississippi became the last state to repeal its state prohibition in 1966, three decade after the 21st Amendment had repealed Prohibition nationally.

One day, the sheriff came into the house and claimed he found alcohol. John’s grandmother knew the sheriff had planted it there. When he told her he was going to haul her to jail, her response traveled deep into John’s soul. She said, “If I was a man, I would kick your a__ for thinking that I would go with you and leave these little ones.” Her defense fueled a sense of dignity in John: his grandmother loved him; she had stood up for him against the white sheriff. He knew then that he was worth as much as any other child.

This incident helped counter the reflection of himself that John saw in the eyes of many others: like when he was 12 and had worked hard all day for a white farmer. Instead of the dollar or two he expected to receive at the end of the day, the man dropped just 15 cents into his hand. John knew what would happen, to both himself and his family, if he did what he wanted to do at the time: throw the money on the floor in front of the man. “We would get the reputation of being ‘Uppity Niggers,’ or worse, ‘Smart Niggers,’” Perkins said. But the incident had made him think and ask questions, and he had made a decision. This man, John realized, had the capital, and could make evil decisions about what to do with it; one day, John decided that he, too, would be in a position to make decisions about his own capital.

Perkins left Mississippi in 1947, after his older brother, Clyde—home from serving in World War II—was shot by the police. He died in John’s arms. Perkins found work in a California foundry where, while still a teenager, he helped to form a union. It gave him a taste of the success that united action could bring.

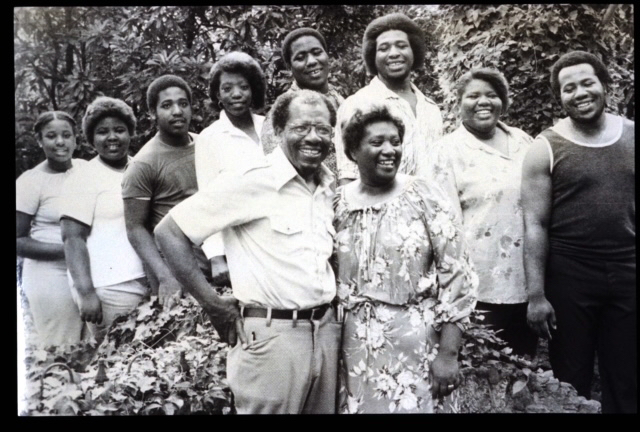

After he was drafted into the Korean War and served two years, John and his bride, Vera Mae, a hometown girl who was the most beautiful woman he had ever seen, settled in Monrovia, California. They’d already had five of their eight kids, and were enjoying a lifestyle better than either of them had known growing up.

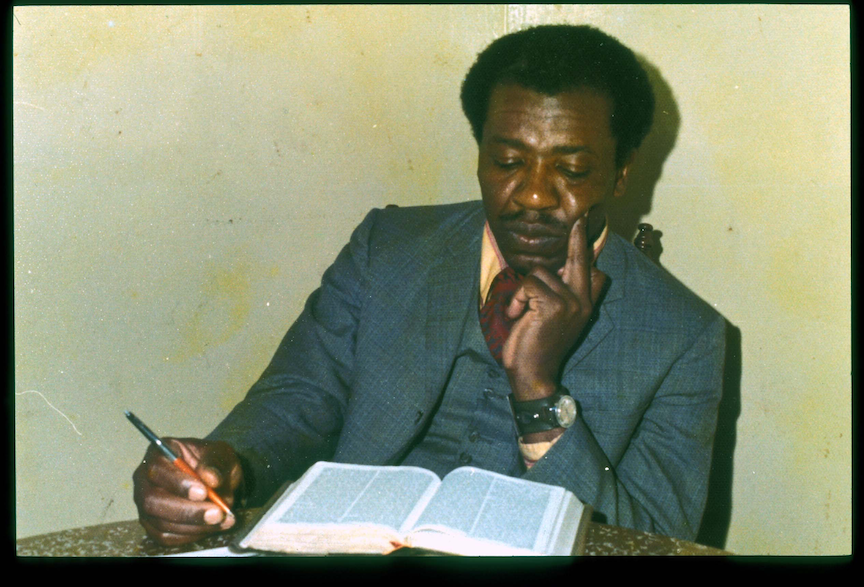

Perkins’ life would change drastically, however, when his oldest son, Spencer, was invited to a local Good News Club. Spencer, still in preschool, then invited his dad to church. John went and started reading the Bible for the first time. One Sunday, he heard Romans 6:23: “For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” He said that verse spoke to his whole life experience. He knew about wages: it was a dime and a buffalo nickel from a white man. And sin—that was oppression. But what about his own sin?

That morning was the culmination of much searching. John said yes to Jesus, had inner peace for the first time, and didn’t look back. “I moved into my new life like I did everything else: as hard as I could,” Perkins said. Soon he felt God calling him back to Mississippi, where he started teaching Bible classes in schools. He and Vera Mae started Mendenhall Ministries, to help break the cycle of poverty and facilitate reconciliation.

The Paradox of Suffering

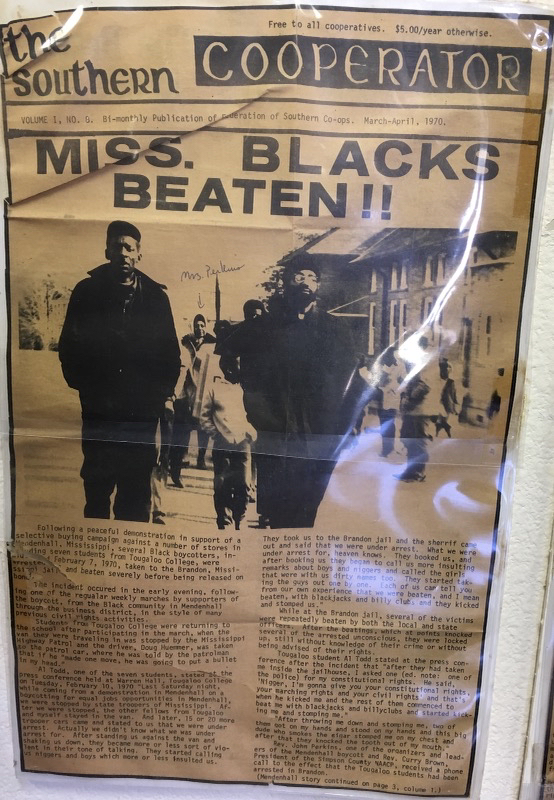

In 1964, civil rights issues were heating up in Mississippi. Everyone, black and white, had to take a stand, Perkins said. He led a voter registration drive, and a few years later, organized a boycott.

In 1970, after several Tougaloo College students had been imprisoned for protesting, Perkins went to the jail in Brandon, Mississippi, to bail them out. When he arrived, Mississippi patrolmen had other plans for him. They tortured and beat him and made him mop up his own blood. It’s not something John can talk about easily. During almost two years of unjust court proceedings, he suffered from heart problems, and had much of his stomach removed because of ulcers.

This led to a faith crisis, which was eventually overcome by individual acts of kindness and love, coming from both God and man: like the white doctor who sat by his bed reading and caring for him and wouldn’t leave until John was asleep. Years later, the arms of a white chaplain would hold him together after hearing the news that Spencer, not yet 50, hadn’t survived a heart attack. “We wash one another’s wounds,” John says quietly.

Perkins has since written 17 books, but not alone. “I’ve been so blessed in my life to have so many people who have given me the help I need. This whole lifetime of ministry has been with friends God has put into my life. It’s a teamwork.” He calls his last three books, his manifesto: the truths he has learned in his 90-plus years, and what he hopes will live on after him.

His first book, “One Blood: Parting Words to the Church on Race and Love,” was published when he was 88. “We are one blood; science has already proven that.” And when we are born again into the family of God, he added, we are also brothers and sisters in the faith.

Book two came after Perkins was asked by a college student how he could make a difference in the world. “Become friends with God, and be friends with each other,” John answered, and then unpacked this response in “He Calls Me Friend: The Healing Power of Friendship in a Lonely World.”

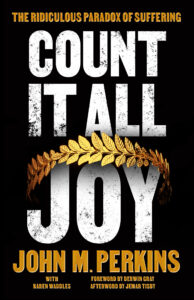

In September 2021, Perkins’ last book was released: “Count it All Joy: The Ridiculous Paradox of Suffering.” This book describes his journey through months of mysterious pain, morphine, and two hospital stays, until the source of the problem was finally found. Behind layers of scar tissue that had grown where doctors had operated following his attack in the Brandon jail, cancer was growing.

Perkins had already beaten cancer twice before he reached 90. The incredible pain of this third journey, however, was different, he wrote. He’d had words for the other pain. But with this one, came the unexpected, and John asked the Lord to give him a little more time. There were things he hadn’t been able to say before: like the value of lamentation. “Lament is an old word that has been given a fresh new meaning in this generation,” Perkins said. “We need to let people know that God allows us to lament. We don’t have to act like we’re strong when we’re falling apart. Life is hard. And it becomes harder when we don’t have safe places to share our grief and our struggles without being made to feel like we’re not strong enough.”

And the paradox in this last book: Perkins makes the case that suffering is good, and it is sometimes God’s way of getting our attention and preparing us for His purposes. He speaks with authority after a journey that has borne the pain of breaking down barriers. His conclusion is a surprising closing hymn: True joy is formed in the crucible of suffering. It isn’t experienced alone. “When I cry out to Him, He meets me right there in the place of my pain. And He feels what I feel. He hurts when I hurt. I believe that,” Perkins declared.

John and Vera Mae, with the support of friends, have started many ministries that focus on Christian community development, multiethnic church planting, health care, education, legal assistance, low-income housing development, and more. It’s clear that John hasn’t let his third-grade education hold him back.

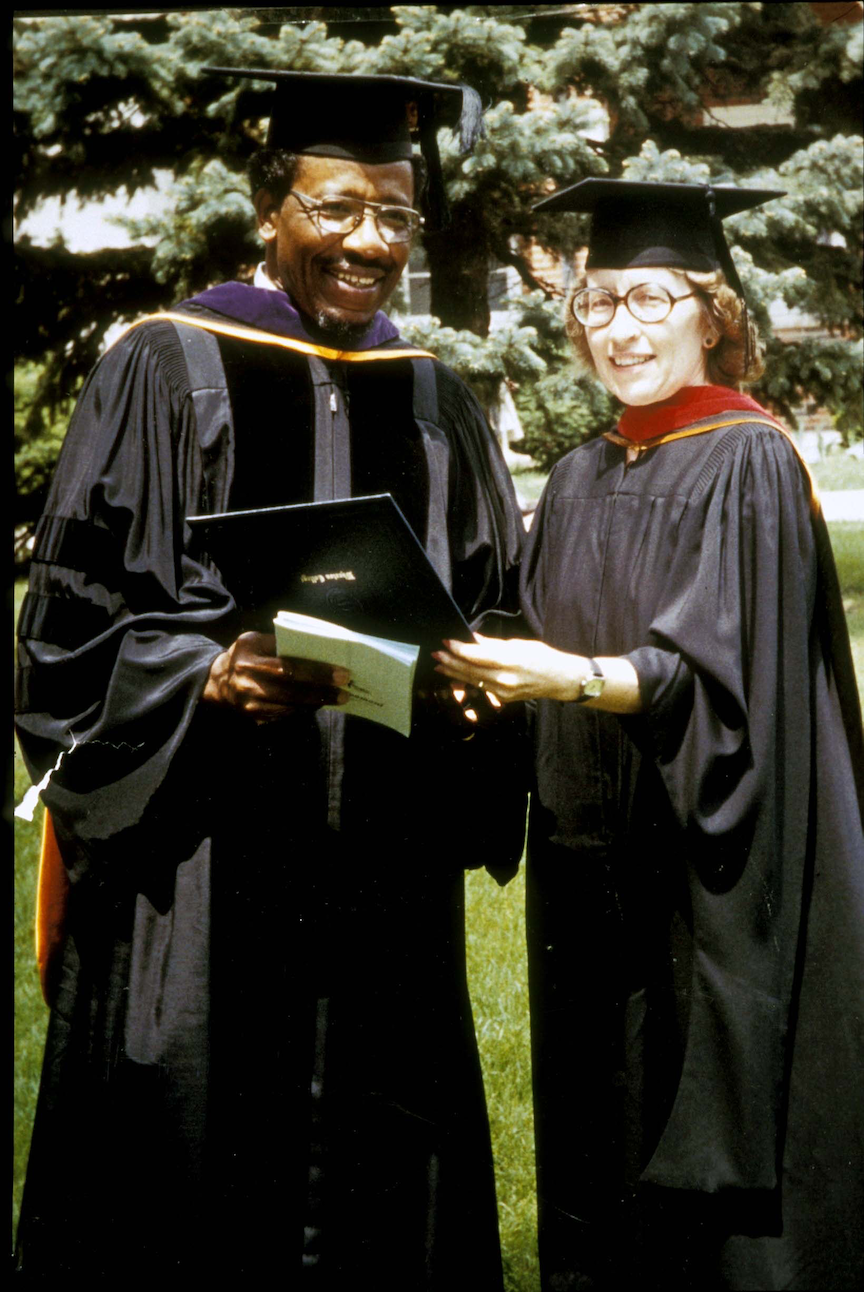

In 1969, his testimony before the McGovern Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs led to The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), a government program that helps feed millions of low-income women, infants and children each month. He has served in an advisory role under several U.S. presidents. He is an international speaker on reconciliation, leadership, and community development. Sixteen colleges have recognized his life and work with honorary doctorate degrees. Three colleges have established John Perkins Centers.

John, now Dr. Perkins, still has hope for the future. “The Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution are the greatest statements on human dignity,” he often says. While America hasn’t always lived up to it, for the first time, Perkins now sees “a generation that values differences. One of the greatest statements in the world” he says, “is ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.’”

Although he’s quick to clarify that he’s still alive, and “still listening,” Perkins has imagined what it’s going to be like when he meets his mother on the other side. He will borrow the words of Thurgood Marshall. “I’m going to say, ‘Momma, I tried. I did what I could with what I had.’” Her response will likely be the second “Well done” that John hears.

For more information about John Perkins, and his free video class on living with purpose and passion, visit JohnMPerkins.com