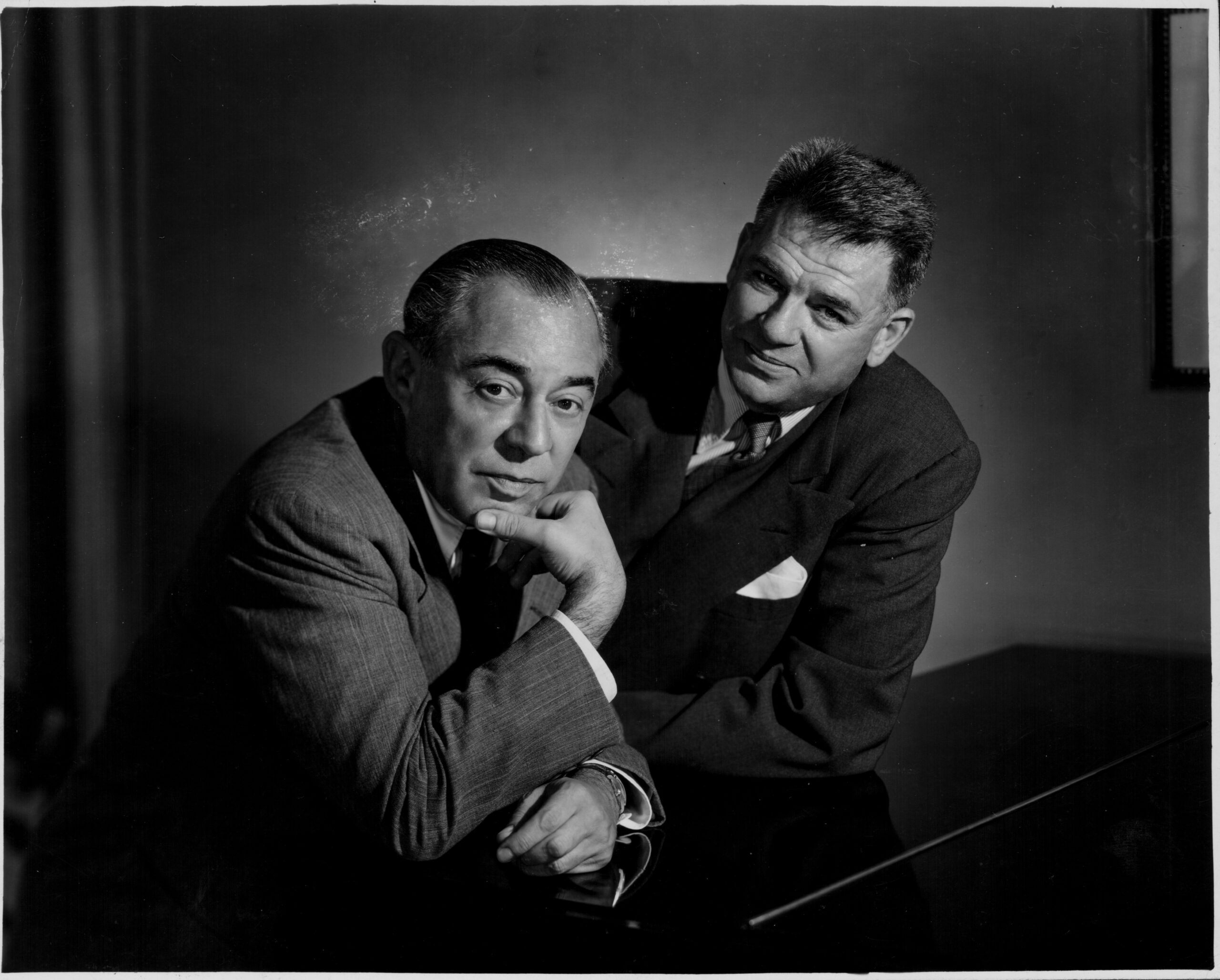

On the evening of March 31, 1943, American musical theater entered its Golden Age. That was the night the curtain at Broadway’s St. James Theatre rose on an old woman churning butter and a cowboy praising the beauty of the morning. It was the night “Oklahoma!” proclaimed the arrival of composer Richard Rodgers and librettist/lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II as a writing team and theatrical force.

The show wasn’t expected to be a hit. “No gags, no girls, no chance,” was the infamous response of a critic who saw “Oklahoma!” in out-of-town previews. Musicals at the time were expected to exhibit a certain degree of glitz that this one lacked. Through the magic of Rodgers’s music and Hammerstein’s words, however, “Oklahoma!” made audiences—and critics—forget all that. It ran for an unprecedented five-plus years.

“Rodgers and Hammerstein,” as the team quickly became known, went on to define the span of the Golden Age they initiated, which for most commentators ends with Hammerstein’s death in 1960. These years, 1943–1960, were the era of the “book musical,” the blending of musical, lyrical, dramatic, and choreographic elements into a seamless whole, each contributing to the tone and meaning of the story. That may seem old-fashioned in a time of jukebox musicals and pop star tributes, but in the 1940s it was the leading edge of innovation.

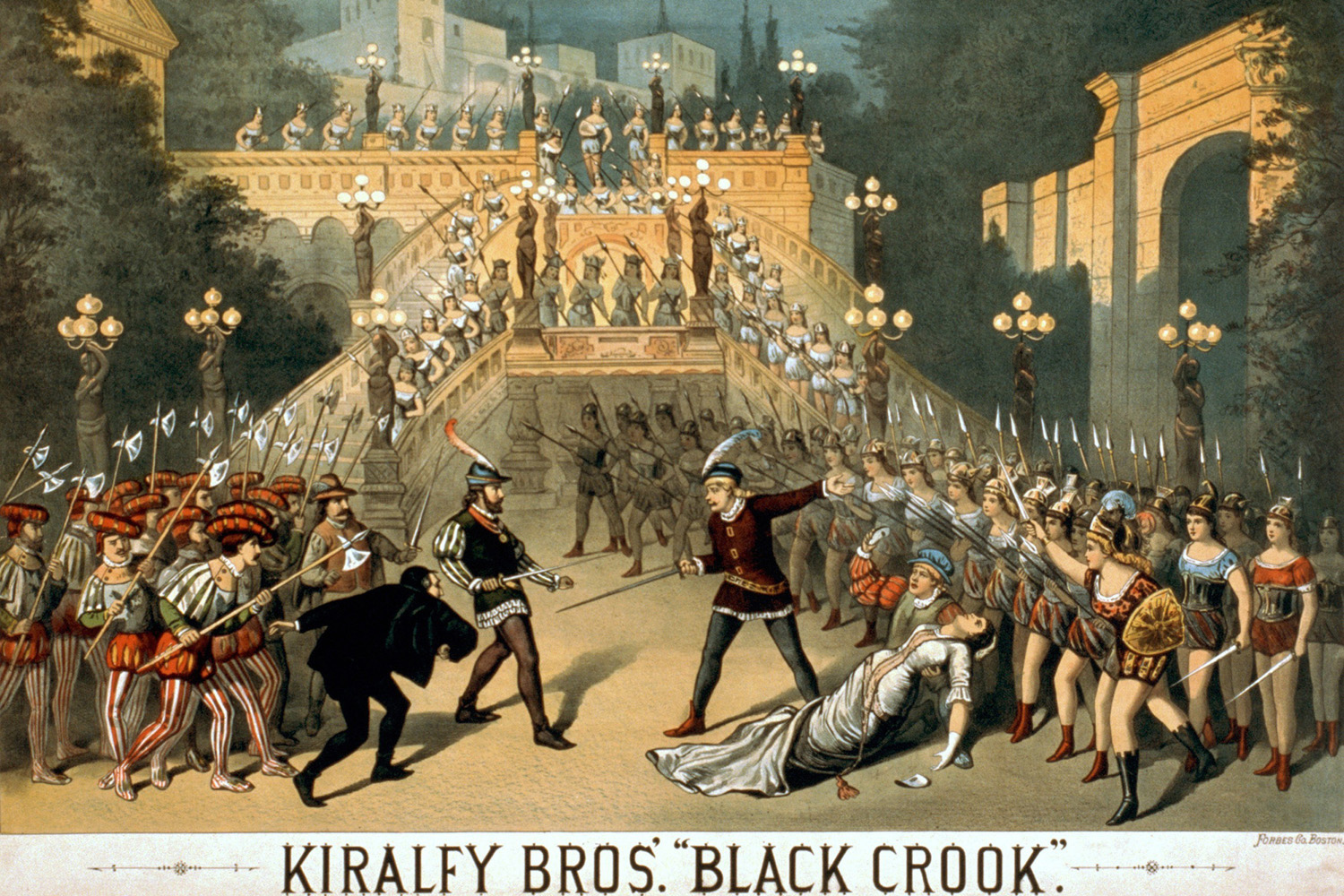

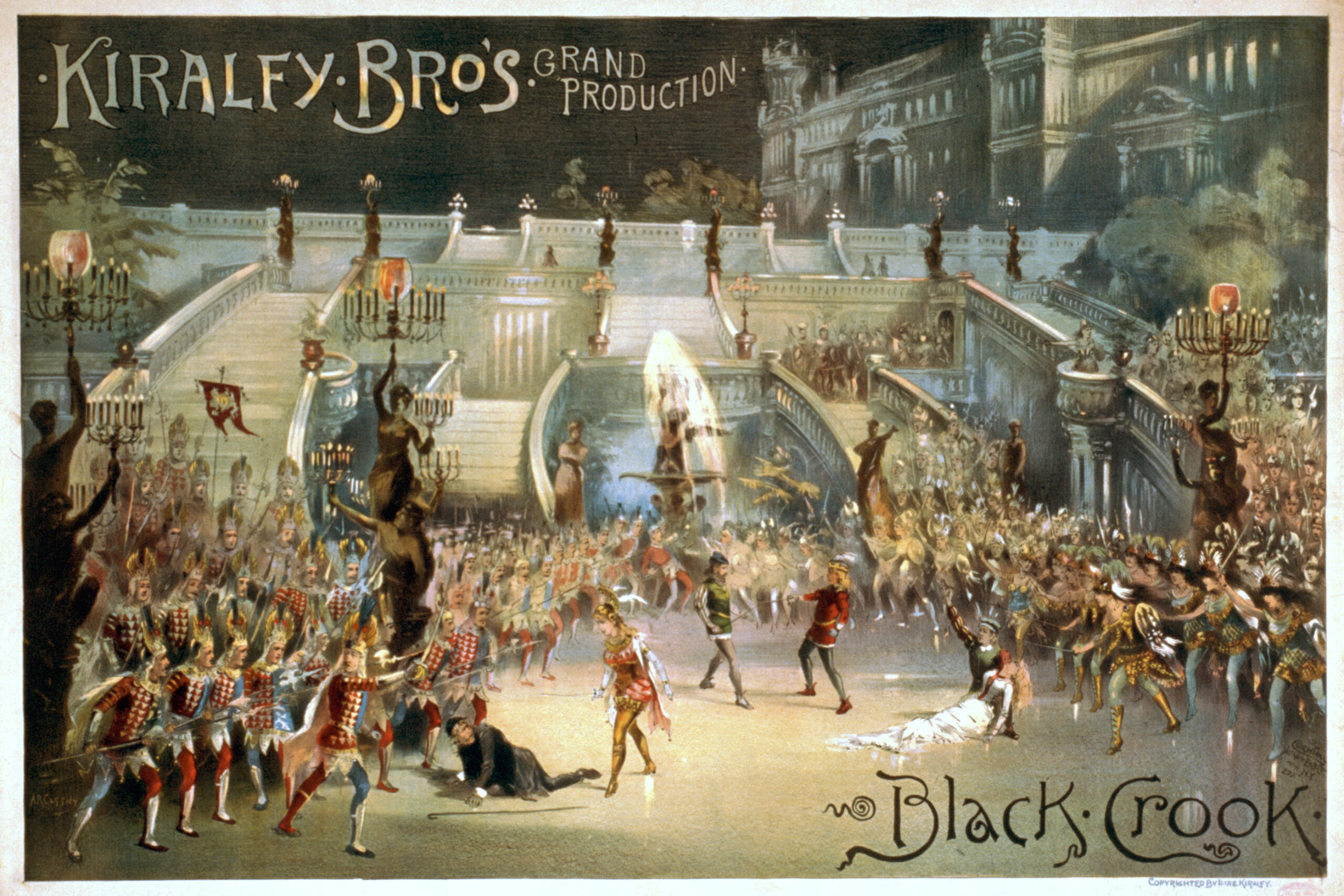

The Birth of the Musical

The American musical began as a hodgepodge of song, dance, and dialogue loosely strung together to tell a story—or sometimes not. The first example is said to be “The Black Crook,” an 1866 grab-bag of tunes and jokes linked to a thin plot. Over the ensuing decades, the American musical painstakingly crawled its way toward the integration of music, dance, and story line into a sophisticated whole. Two giant steps in that direction were “Showboat” (1927) and “Pal Joey” (1940). Hammerstein wrote the dialogue and lyrics for “Showboat” while Rodgers was the composer of “Pal Joey.”

Prior to 1942, Rodgers had been working with lyricist Lorenz “Larry” Hart on musicals that slowly advanced the notion of an integrated whole, culminating in “Pal Joey.” But Hart was plagued with personal problems, drank heavily, and was increasingly difficult to work with. Rodgers, intent on turning a little comedy called “Green Grow the Lilacs” into a musical, knew Hart wasn’t up to it. He asked Hammerstein, whose work on “Showboat” he admired, and Hammerstein said yes.

It was a match made in theatrical heaven. Rodgers, tired of the urban style he used with Hart, turned to a more broadly lyrical, operetta-like musical language flecked with American folk elements. Hammerstein’s poetic lyrics matched this and evoked atmosphere, character, and sensibility in a way no popular lyrics of the time did. He could dream into the hearts of a young couple and find them fantasizing about a “Surrey with the Fringe on Top,” or imagine the plaint of an outcast (Judd) in his “Lonely Room.”

American Stories Told Through American Music

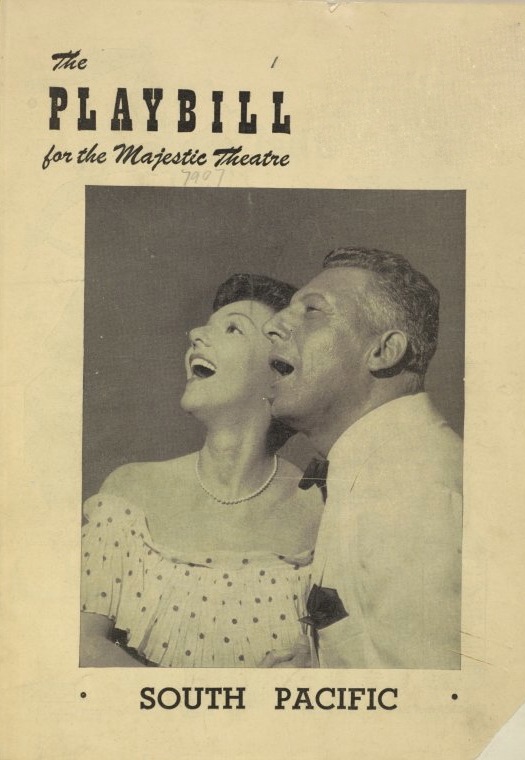

“Oklahoma!” and the three remaining Rodgers and Hammerstein shows of the 1940s concern American characters. “Carousel” (1945) finds us in New England, witnessing the tragic yet transcendental romance of Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan. “Allegro” (1947), the only box-office failure of the four, traces the life of an American doctor. “South Pacific” (1949) considers the lives of American servicemen and women in World War II.

In the 1950s, however, the musicals moved beyond American shores. The two biggest Rodgers and Hammerstein hits of that decade focus on an English lady tutor in 19th-century Siam (“The King and I,” 1951) and a singing Austrian family fleeing the Nazis (“The Sound of Music,” 1959). Their only ’50s box office success set in America was “Flower Drum Song” (1958), considered “minor” Rodgers and Hammerstein. Their TV musical “Cinderella” (1957) used European fairy tale material.

The fading of the book musical is not surprising, given the nature of contemporary song. Traditional popular song, the framework for Rodgers’s music, was harmony-based, whereas current pop is largely beat-based and harmonically much narrower than the earlier type. Harmony was central to creating the appropriate musical language for a book show.

Creating a Musical Universe

All the songs in “Carousel” have a certain melodic gesture in them. This gesture, based on a specific interval between notes (the augmented fourth) generates shared harmonies among the various songs. That’s why numbers as rhythmically distinct as “If I Loved You” and “June Is Busting Out All Over” belong to the same universe: Their harmonic structures are related. But one song is an exception: “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” That’s the hymn Carrie sings to comfort Julie when Billy dies, and the reason it feels transcendent, separate from the others, is that it is harmonically unique. Rodgers and the other composers of the Golden Age didn’t just make up tunes willy-nilly. A deep craftsmanship informed their art.

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s catalogue is today a frequent target of critics who bandy about words like “conventional” and “bourgeois” as if the values represented by them are automatically to be dismissed as out of date. But the clock, as G.K. Chesterton once observed, is a human invention, and humans may set it back any time they wish. Perhaps it’s time to dial our musical theater clocks back to the era of Rodgers and Hammerstein.

From April Issue, Volume 3